Paul Collins (1)Interview

Auteur van Sixpence House: Lost in A Town Of Books

Voor andere auteurs genaamd Paul Collins, zie de verduidelijkingspagina.

Paul Collins (1) via een alias veranderd in Paul S. Collins.

Auteursinterview

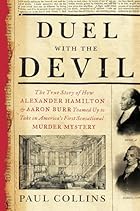

Paul Collins teaches in the MFA program at Portland State University, and is the author of many books, including Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books, The Book of William, and more. He's also NPR's "literary detective," and writes for a wide variety of publications. His new book, Duel with the Devil was published in June by Crown.

Paul Collins teaches in the MFA program at Portland State University, and is the author of many books, including Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books, The Book of William, and more. He's also NPR's "literary detective," and writes for a wide variety of publications. His new book, Duel with the Devil was published in June by Crown.

In Duel with the Devil you tell the story of a gruesome 1799 New York City murder case in which a young woman's suitor is accused of causing her death. The young man puts together something of a "dream team" of defense lawyers: who were his attorneys, and how did he manage to obtain such impressive counsel?

The defendant, Levi Weeks, managed to get the three best lawyers in NYC: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and Brockholst Livingston. Weeks was a construction foreman, but his brother Ezra Weeks happened to be the most successful developers in the city—and Hamilton and Burr were both clients of his! Hamilton in particular was running up an impressive tab (which he couldn't pay) having Weeks build him a mansion, so he certainly owed a favor.

I might add that while Livingston's the least known of the trio, he was no slacker himself: the guy was later appointed to the Supreme Court.

This wasn't the only time Hamilton and Burr found themselves on the same side of a courtroom, right? What others sorts of cases did they cooperate on?

They usually worked on commercial cases—property disputes, insurance cases over lost ships, that sort of thing. They were often on opposite sides, but not always—in fact, right before this case, they'd wrapped up a monster settlement for a client named Louis Le Guen. Since Aaron Burr was even worse with money than Hamilton, he promptly asked Le Guen for a loan!

What sources did you find most useful in reconstructing the trial? Is this case different from others from the same time in terms of the amount of source material available?

What sources did you find most useful in reconstructing the trial? Is this case different from others from the same time in terms of the amount of source material available?

For the trial itself, it was three competing accounts of the trial published in the weeks afterwards—particularly one published by the court's clerk, William Coleman. Coleman's transcript was essentially the first American murder trial transcript to include both questions and answers. That was a huge, huge deal. Now I could have people talking on the page—and talking back and forth with each other, since he gives both sides of the conversation. And better still, you have witnesses testifying to what they and other people said at the time of the crime, too. Once you have that ability to render dialogue on the page, it comes alive; it's like going from black & white to color.

You managed to uncover what may well be the first new evidence in this case in more than two centuries. What did you find, and how did come across it?

I'd like to say that I found it after a long and arduous search, and that it involved a massy oaken door creaking open onto a dusty archive, but…nah. Truth be told, it was pretty much the first thing I found. I came across a brief account of the trial in a 1914 work called American State Trials, and my first thought was—"What the hell? Burr and Hamilton on a murder case?" But my second thought was: Huh, I wonder if any of these people had a past criminal record in Britain. And so I went over to Old Bailey Online—which is an amazing site, by the way, one I get lost in for hours—and I started plugging in names. And there it was.

Of course, as I dived deeper in the case, exactly what that new evidence meant became clearer to me. But it certainly reinforced the idea of what it meant to live in era where someone's past isn't just a few clicks away, where by moving to another country, or even another state, you could just reinvent yourself, and nobody would ever know.

You've got one of the best titles out there, as NPR's "literary detective." I'd love to hear a bit about how you seek out the sorts of fascinating historical stories you like to tell: do you go in search of them, or do they tend to be just things you've stumbled across in the course of other research and then decide to follow up on?

Often I'll just grab random old newspapers and magazines (in libraries or online) and start snooping, but a surprising amount of the time it's weird, random stuff I find while looking up something else. Chance favors the prepared mind and all that.

On this book in particular, though, a lot of the small and odd details came pretty systematically—namely, I read through nearly every available Manhattan newspaper from 1799 and 1800. That's not quite as insane as it sounds, because newspapers back then were 4 pages long! Still, it was thousands of pages, but that's always my favorite part of writing—wandering through those lost-dog notices and molasses shipments and yellow fever quack cures. Probably a whole bunch of other stories will now spin off from that experience.

As you've researched such a varied range of topics, what are some of the things you've found that have particularly surprised you?

My favorite recent find was the likely model for the Dickens character of Miss Havisham—and story also doubled as the explanation behind a famous haunted house. And it's set in Maggs Bros. bookstore in London, no less. That's behind the app paywall at Mental Floss, so it really didn't get any play online, but I just love tugging on a loose end like that and having turn into one of those endless magician's handkerchiefs.

A couple of my favorite other find both became pieces for The New York Times. One was on advertising in paperbacks—something I remembered from when I was a kid—and that simply started when I looked at UCSF's "tobacco papers" archive and idly wondered, "Hmm, what'll turn up if I type in 'paperback'?" Another was tracking down the unknown author of the first detective novel, The Notting Hill Mystery. That story resulted in the British Library doing a proper reissue of the book, which pleased me to no end.

Do you have plans to collect some (or all) of your essays and articles into book form? If not, may I humbly beg you to do so?

t will torture any fans for me to reveal this, but I actually did rewrite and pull together a bunch of pieces in 2005... and then got sidetracked into my next book (The Book Of William). Now I've got another 8 years worth sitting around, and…I sat down one day and tallied it up, and there's the better part of a thousand pages now uncollected. I really will get around to it someday. Hopefully before I hit another thousand pages!

What's your library like? What kinds of books would we find on your shelves?

It's very peculiar. I'm quite ruthless about using digital, interlibrary loans, etc etc. What's in my library are the orphans, just the weird old books that I bought because I liked the cover, and castoffs from past projects, or books I think I might like republishing someday. It's a dog's breakfast of a collection, and nobody would know what the hell to make of it. Though they would find a lot of Harry Stephen Keeler. I have more Keelers than should be legally allowed. He's my one vice as a collector.

What books have you read and enjoyed recently?

The British Library recently reissued Andrew Forrester's Victorian pulper The Female Detective (1864), which I'd never read before and was fascinated by. As a writer, I really love the premise of Alexandra Horowitz's new book On Looking—basically, walking around the same NYC neighborhood eleven times with different kinds of experts observing it each time. And as someone fascinated by disastrously bad movies, I'm excited to see Tom Bissell's upcoming The Disaster Artist, about the making of "The Room." I was actually with Tom the first time either of us saw it, and…wow. Just…wow.

Also, I've just come off a Wodehouse reading jag. After eight or nine of his books in row I felt like I'd consumed an entire sheet cake, but it's a testament to him that, well, I'm seriously thinking of reading a tenth.

Can you give us a sense yet of what project(s) you're working on now?

I just finished a biography of Edgar Allan Poe which should be out next year, and it was a joy to immerse myself in that. I'm now in the early stages of my next project, another 19th century murder case. That might be my next few books, actually. Court records and newspaper coverage give you this extraordinary cross-section of everyday life in another era—you have all that testimony to work with, people talking about what they did and said on a particular day, before it was interrupted by this event—to be able to see right into another century like that is catnip for a historian.