1wandering_star

A quick first post to say that I am once again looking forward to a year of hearing about everyone's reading, and discussing books, in this group.

I'm also reposting from my 2019 thread my list of favourites.

+++

These were my top rated books in 2019 (in reverse order of date read):

5*

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor

The Lost Man by Jane Harper

Visitation by Jenny Erpenbeck

The Watcher in the Pine by Rebecca Pawel

My Favourite Thing is Monsters by Emil Ferris

4.5*

Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun

The Girl from Everywhere by Heidi Heilig

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

And looking back, the books that have stood out and which I've been recommending are (in order of preference):

Visitation by Jenny Erpenbeck (the story of a house by a lake in Eastern Germany and the people who lived in it over the course of the 20th century, told in a semi-experimental style)

Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad (atmospheric scenes from the past, present and future of Bangkok, linked by the fact that all the characters live in the same place)

Milkman by Anna Burns (I gave this four stars because I found it a bit long, but the way that the author uses language to show all the social constraints on people, and all the things which couldn't be said, is really unique and powerful)

My Favourite Thing is Monsters by Emil Ferris (graphic novel - a misfit young girl draws her own life and the life story of a mysterious upstairs neighbour)

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun (a young girl lives a peripatetic lifestyle in Europe after her charismatic but self-indulgent father flees Nazi Germany)

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker (the Trojan war, retold from a feminist standpoint)

The Lost Man by Jane Harper (top-quality crime, in which the harshness of outback Australia is almost a character in its own right - the same author's Force of Nature was a 4* read for me this year)

The Cutting Season by Attica Locke (another excellent crime, bringing together two mysterious deaths, the historic one of a plantation slave and the contemporary one of a Latin American migrant worker)

I'm also reposting from my 2019 thread my list of favourites.

+++

These were my top rated books in 2019 (in reverse order of date read):

5*

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor

The Lost Man by Jane Harper

Visitation by Jenny Erpenbeck

The Watcher in the Pine by Rebecca Pawel

My Favourite Thing is Monsters by Emil Ferris

4.5*

Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun

The Girl from Everywhere by Heidi Heilig

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

And looking back, the books that have stood out and which I've been recommending are (in order of preference):

Visitation by Jenny Erpenbeck (the story of a house by a lake in Eastern Germany and the people who lived in it over the course of the 20th century, told in a semi-experimental style)

Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad (atmospheric scenes from the past, present and future of Bangkok, linked by the fact that all the characters live in the same place)

Milkman by Anna Burns (I gave this four stars because I found it a bit long, but the way that the author uses language to show all the social constraints on people, and all the things which couldn't be said, is really unique and powerful)

My Favourite Thing is Monsters by Emil Ferris (graphic novel - a misfit young girl draws her own life and the life story of a mysterious upstairs neighbour)

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun (a young girl lives a peripatetic lifestyle in Europe after her charismatic but self-indulgent father flees Nazi Germany)

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker (the Trojan war, retold from a feminist standpoint)

The Lost Man by Jane Harper (top-quality crime, in which the harshness of outback Australia is almost a character in its own right - the same author's Force of Nature was a 4* read for me this year)

The Cutting Season by Attica Locke (another excellent crime, bringing together two mysterious deaths, the historic one of a plantation slave and the contemporary one of a Latin American migrant worker)

4ELiz_M

Happy New Year! I always enjoy your reviews and am looking forward to what you're reading this year.

5raton-liseur

Happy new year! I'm looking forward to following your reading journey this year!

6dchaikin

Quietly, mainly, but I'm following and taking notes on the gems that pop up. Happy New Year.

7wandering_star

Hi everyone! Lovely to see you all here.

1. Lumberjanes, Vol 1 by Noelle Stevenson, Shannon Watters and Grace Ellis

I wasn't really planning for this to be my first read of the year. But it turns out that it's one of those 'Volume Ones' which is in effect the first chapter of a story, so before I knew it, it was over!

It also makes it a little bit hard to review, as this was a library book and the library doesn't have any of the other books in the series (my resolution for 2020 is not to acquire any new stuff, but I'm allowing myself to borrow books).

But for what it's worth: a group of friends are away at summer camp. One night they have sneaked out of their cabin and are having strange adventures in the woods. Their cabin leader catches them and hauls them over to the camp leader for a telling off, but her reaction to their story suggests that she'll be more forgiving than the cabin leader.

And - that's where the volume ends. Not a lot for £11, which is the full cost of the hard copy of the book.

It seemed fun and if there had been more I would have read on. But that's kind of all I can say by way of a review.

1. Lumberjanes, Vol 1 by Noelle Stevenson, Shannon Watters and Grace Ellis

I wasn't really planning for this to be my first read of the year. But it turns out that it's one of those 'Volume Ones' which is in effect the first chapter of a story, so before I knew it, it was over!

It also makes it a little bit hard to review, as this was a library book and the library doesn't have any of the other books in the series (my resolution for 2020 is not to acquire any new stuff, but I'm allowing myself to borrow books).

But for what it's worth: a group of friends are away at summer camp. One night they have sneaked out of their cabin and are having strange adventures in the woods. Their cabin leader catches them and hauls them over to the camp leader for a telling off, but her reaction to their story suggests that she'll be more forgiving than the cabin leader.

And - that's where the volume ends. Not a lot for £11, which is the full cost of the hard copy of the book.

It seemed fun and if there had been more I would have read on. But that's kind of all I can say by way of a review.

8wandering_star

2. Lucia by Alex Pheby

This novel tells the story of Lucia Joyce, daughter of James, and someone who led an extraordinary and troubled life. She was a dancer, who took on a small role in a Jean Renoir film. She was friends with Samuel Beckett (with whom she may have had a short affair), had a relationship with Alexander Calder (who was teaching her drawing) and was treated by Carl Jung, but was diagnosed with schizophrenia in her late twenties and spent much of the rest of her life in institutions, until she died at the age of 75.

There is a controversial theory that Lucia was sexually abused by her brother as a child: Pheby picks this up in this book, as well as including similar mistreatment by her father and many other men she comes into contact with. He tells her story elliptically: many of the chapters are told from the point of view of unnamed men, and you have to watch out for the one sentence or reference which tells you how their lives intersected with Lucia's. But in almost every story there is something about the general cruelty of the world to the powerless, reflected in but much larger than Lucia's own life.

The chapters are also interleaved with a short story about an archaeologist discovering an Egyptian tomb, which appears to have been desecrated before it's been sealed. He concludes that this is because the dead woman in the tomb was believed by her family to have been cursed, and so they didn't want her to have the usual protections in the afterlife. This is a reference both to the family's destruction of papers relating to Lucia Joyce, and to Pheby's own efforts in writing this book.

So it's all very clever. And I do think in principle it's possible to write a clever book about someone who is treated appallingly without losing a sense of that person as a human being (for example, The Clocks In This House All Tell Different Times which is similarly a 'clever' book about an abused child, which doesn't forget the person at the centre of the story). But I don't think that Lucia does that.

That is troubling in a human sense. But after a while it also started to make the book a bit boring. As I started each new chapter I knew that it would be about someone who is treating other people badly, but told through that character's self-justification. I knew that there would be one detail which was really gross, but told in the same bloodless way as the rest of the chapter. And I knew that the whole thing would appeal only to the intellect and not the emotions.

They are cold themselves, hungry themselves, hopeless themselves, differing from her only by degree, and there but for the grace of God go we, and all the sooner if we waste money we don’t have on matches we don’t need for children who misrepresent themselves on the street on New Year’s Eve, when the numbers reach the end and begin again.

It is hard, though, to misrepresent death.

It is equally hard to represent oneself as having a conscience when one does not.

She cares about none of this: neither that they do not care for her, nor that they might be induced to care for her once she is dead. It is a condition of care that it comes after the event, when one can be sure it is merited and after there is any practical requirement on one to do anything except feel appalled. Felling appalled is a very trivial matter, and something that can be done whilst going about one’s normal business without it impacting too much.

This novel tells the story of Lucia Joyce, daughter of James, and someone who led an extraordinary and troubled life. She was a dancer, who took on a small role in a Jean Renoir film. She was friends with Samuel Beckett (with whom she may have had a short affair), had a relationship with Alexander Calder (who was teaching her drawing) and was treated by Carl Jung, but was diagnosed with schizophrenia in her late twenties and spent much of the rest of her life in institutions, until she died at the age of 75.

There is a controversial theory that Lucia was sexually abused by her brother as a child: Pheby picks this up in this book, as well as including similar mistreatment by her father and many other men she comes into contact with. He tells her story elliptically: many of the chapters are told from the point of view of unnamed men, and you have to watch out for the one sentence or reference which tells you how their lives intersected with Lucia's. But in almost every story there is something about the general cruelty of the world to the powerless, reflected in but much larger than Lucia's own life.

The chapters are also interleaved with a short story about an archaeologist discovering an Egyptian tomb, which appears to have been desecrated before it's been sealed. He concludes that this is because the dead woman in the tomb was believed by her family to have been cursed, and so they didn't want her to have the usual protections in the afterlife. This is a reference both to the family's destruction of papers relating to Lucia Joyce, and to Pheby's own efforts in writing this book.

So it's all very clever. And I do think in principle it's possible to write a clever book about someone who is treated appallingly without losing a sense of that person as a human being (for example, The Clocks In This House All Tell Different Times which is similarly a 'clever' book about an abused child, which doesn't forget the person at the centre of the story). But I don't think that Lucia does that.

That is troubling in a human sense. But after a while it also started to make the book a bit boring. As I started each new chapter I knew that it would be about someone who is treating other people badly, but told through that character's self-justification. I knew that there would be one detail which was really gross, but told in the same bloodless way as the rest of the chapter. And I knew that the whole thing would appeal only to the intellect and not the emotions.

They are cold themselves, hungry themselves, hopeless themselves, differing from her only by degree, and there but for the grace of God go we, and all the sooner if we waste money we don’t have on matches we don’t need for children who misrepresent themselves on the street on New Year’s Eve, when the numbers reach the end and begin again.

It is hard, though, to misrepresent death.

It is equally hard to represent oneself as having a conscience when one does not.

She cares about none of this: neither that they do not care for her, nor that they might be induced to care for her once she is dead. It is a condition of care that it comes after the event, when one can be sure it is merited and after there is any practical requirement on one to do anything except feel appalled. Felling appalled is a very trivial matter, and something that can be done whilst going about one’s normal business without it impacting too much.

9lilisin

Always great to find your thread and hope we will get a chance to see each other again this year.

10wandering_star

>9 lilisin: in the absence of being able to come to Japan, here's a review of a Japanese book!

3. Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

Keiko has never really understood other human beings. Things which seem perfectly normal to her (hitting two fighting teenagers with a spade, as the quickest way to stop them fighting; cooking a dead bird she finds in the park) make them react in strange ways. She feels fortunate, therefore, to have a job in a convenience store, where she always knows what is the appropriate thing to do.

I was good at mimicking the trainer’s examples and the model video he’d shown us in the back room. It was the first time anyone had ever taught me how to accomplish a normal facial expression and manner of speech.

By close observation and imitation of normal people, and with a bit of help from her sister in coming up with plausible excuses why she's been working at the same convenience store for the last eighteen years, Keiko manages to fit in, as long as no-one asks too many questions. But one day someone does ask too many questions and Keiko concludes that a new approach is needed.

I actually really liked Keiko - particularly her description of the way that she copies the speaking and dressing style of age-appropriate colleagues. I'd actually have been happy to read a book about her quietly getting on with her existence, and am rather sorry that Murata, like her protagonist, felt that something needed to happen to bring events to a head. I enjoyed that part of the story much less.

3. Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

Keiko has never really understood other human beings. Things which seem perfectly normal to her (hitting two fighting teenagers with a spade, as the quickest way to stop them fighting; cooking a dead bird she finds in the park) make them react in strange ways. She feels fortunate, therefore, to have a job in a convenience store, where she always knows what is the appropriate thing to do.

I was good at mimicking the trainer’s examples and the model video he’d shown us in the back room. It was the first time anyone had ever taught me how to accomplish a normal facial expression and manner of speech.

By close observation and imitation of normal people, and with a bit of help from her sister in coming up with plausible excuses why she's been working at the same convenience store for the last eighteen years, Keiko manages to fit in, as long as no-one asks too many questions. But one day someone does ask too many questions and Keiko concludes that a new approach is needed.

I actually really liked Keiko - particularly her description of the way that she copies the speaking and dressing style of age-appropriate colleagues. I'd actually have been happy to read a book about her quietly getting on with her existence, and am rather sorry that Murata, like her protagonist, felt that something needed to happen to bring events to a head. I enjoyed that part of the story much less.

11valkyrdeath

Stopping by to follow your thread, looking forward to another year.

>7 wandering_star: I really enjoyed the first few volumes of Lumberjanes when I read them, but I do wish they'd stop collecting comics in groups of four issues and releasing them as a book. When it's a long ongoing series, those volumes always feel so insubstantial. I'd far rather they wait a bit longer and create a bigger book, but I guess they'd make less money that way.

>7 wandering_star: I really enjoyed the first few volumes of Lumberjanes when I read them, but I do wish they'd stop collecting comics in groups of four issues and releasing them as a book. When it's a long ongoing series, those volumes always feel so insubstantial. I'd far rather they wait a bit longer and create a bigger book, but I guess they'd make less money that way.

12avaland

Just now getting over here to say I'll be stopping by from time to time. I enjoyed the Convenience Store Woman also.

ETA: I've also enjoyed every Attica Locke I've read (3?)

ETA: I've also enjoyed every Attica Locke I've read (3?)

15wandering_star

4. The Torso by Helene Tursten

Scandinavian thriller, which starts when a dog-walker discovers part of a human body on the beach.

The things I liked most about this were the interesting culture clashes between the Swedes and the Danes (the body washes up in Sweden, but has links to another similar murder which had taken place in Denmark); and the feminist angle (lots of senior women, who get varying degrees of respect from their male colleagues - and the bodies which pile up are not female - although that brings along some rather dated attitudes to homosexuality).

Other than that, though, I thought this was a perfectly fine, simple crime novel - nothing really stood out for me.

Jens Metz asked Jonny if he wanted a “little one.” Jonny said that he craved a Danish schnapps even though it was only ten o’clock in the morning. When the dark schnapps came, Jens toasted with his coffee cup and Jonny with his shot glass, just like two old friends. I wonder what the reaction would have been if I had been the one with the hangover and had arrived two hours late, thought Irene. She was quite certain that no one would have pounded her on the back and called her “dear friend” or offered her an eye-opener. The Danish colleagues would have thought that an intoxicated female police officer was an abomination, probably a drunk, and a bad cop.

Scandinavian thriller, which starts when a dog-walker discovers part of a human body on the beach.

The things I liked most about this were the interesting culture clashes between the Swedes and the Danes (the body washes up in Sweden, but has links to another similar murder which had taken place in Denmark); and the feminist angle (lots of senior women, who get varying degrees of respect from their male colleagues - and the bodies which pile up are not female - although that brings along some rather dated attitudes to homosexuality).

Other than that, though, I thought this was a perfectly fine, simple crime novel - nothing really stood out for me.

Jens Metz asked Jonny if he wanted a “little one.” Jonny said that he craved a Danish schnapps even though it was only ten o’clock in the morning. When the dark schnapps came, Jens toasted with his coffee cup and Jonny with his shot glass, just like two old friends. I wonder what the reaction would have been if I had been the one with the hangover and had arrived two hours late, thought Irene. She was quite certain that no one would have pounded her on the back and called her “dear friend” or offered her an eye-opener. The Danish colleagues would have thought that an intoxicated female police officer was an abomination, probably a drunk, and a bad cop.

16wandering_star

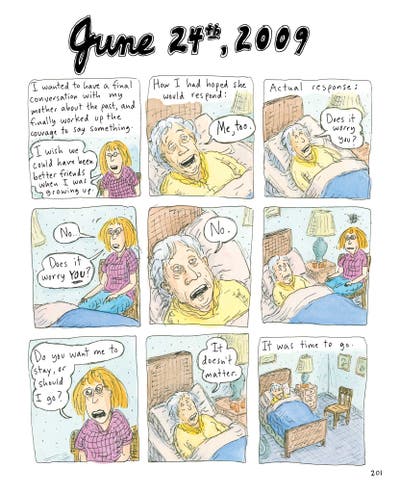

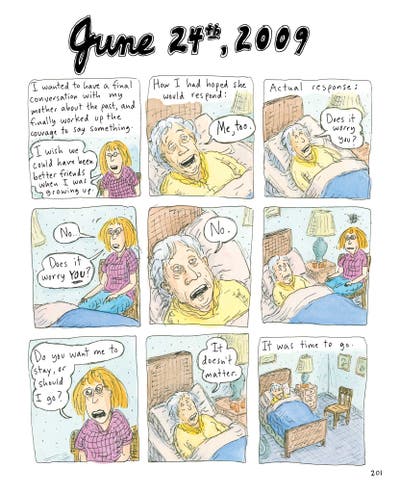

5. Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? by Roz Chast

A graphic memoir (ie comic book format, not gruesome, although it's sometimes also that) about the author's relationship with her elderly parents.

It's been billed as something funny, and to start off it is - particularly as Chast's parents concerns and preoccupations are very similar to my mother's (and elderly immigrants everywhere, I suppose). But as it continues it is brutally honest about the subject of her parents' decline and what this meant for the family in practical terms. And again, this hit harder for me because I'd laughed in recognition so much at the earlier parts of the book.

Really good, and to be recommended, but sometimes a tough read.

A graphic memoir (ie comic book format, not gruesome, although it's sometimes also that) about the author's relationship with her elderly parents.

It's been billed as something funny, and to start off it is - particularly as Chast's parents concerns and preoccupations are very similar to my mother's (and elderly immigrants everywhere, I suppose). But as it continues it is brutally honest about the subject of her parents' decline and what this meant for the family in practical terms. And again, this hit harder for me because I'd laughed in recognition so much at the earlier parts of the book.

Really good, and to be recommended, but sometimes a tough read.

17wandering_star

6. Billion Dollar Whale by Tom Wright & Bradley Hope

An eye-watering story digging into the fraud behind the 1MDB scandal, in which hundred of millions of US$ were stolen from an account supposedly set up to finance infrastructure and other development projects in Malaysia.

The Whale of the title (a reference to what clubs and casinos call their big spenders) is a young Malaysian man called Jho Low, who from an early age loved to host lavish parties and throw lots of money around. On one occasion described in the book, while hanging out with Paris Hilton, Low spent €2m on champagne in a single night (needless to say, this bought more champagne than the whole club-ful of people could drink). But the authors are just as critical of the supposedly reputable banks, auditors and other institutions who were happy to accept and facilitate very dubious-looking deals, as long as a cut of the profits was rolling in their direction.

It's a well-written book, which helps to explain the financial flows just as well as it characterises Low's big-spending habits. One thing I found very curious was the way that Low managed to attract some genuine A-list celebrities to hang out with him. I mean, it's easy to imagine Hilton and the other Z-listers in the book making as much money as possible while they can. But Alicia Keys? Jamie Foxx? The authors explain how Leonardo di Caprio and Martin Scorsese were happy to work with Low because they got complete creative control of their work. (Low's company famously financed The Wolf of Wall Street, which it turns out Warner Bros were not willing to support because they didn't think an R rated film would make its money back. This meant that Scorsese got to crash a real Lamborghini in the opening scene - Warner Bros would have demanded he use a replica. One fascinating snippet is that one of the people who saw through Low very quickly was Jordan Belfort, the subject of Wolf of Wall Street, who after one of Low's parties apparently said "This is a fucking scam ... You wouldn't spend money you'd worked for like that.").

In a strange way, Low is a vacuum at the heart of the book. Other than wanting to be seen and to throw parties, it's hard to know what drove him. Perhaps if he ever stops being a fugitive from justice and comes to trial, we will be able to find out more.

Ordinary folk often get questioned by their banks for small transfers of money. But billionaires are not ordinary. By this point, Low was by far the biggest client that BSI had anywhere in the world, and he was making a lot of people in the bank richer than they ever could have hoped. He was referred to as “Big Boss” in the bank’s Singapore offices, and senior BSI executives would join him for parties in Las Vegas and on yachts. The bank’s senior executives would do all they could to keep Low’s business. Within days of Low’s email*, BSI’s top executives approved the $110 million transfer. “Intra family transfers are not always going to be logical,” a senior BSI banker wrote in response to the compliance officer’s concerns.

*claiming that a transfer that had been routed from one of Low's accounts through his father's account and into another of his accounts was a simple case of a Confucian son trying to give money to his honoured father, who then gave it back.

An eye-watering story digging into the fraud behind the 1MDB scandal, in which hundred of millions of US$ were stolen from an account supposedly set up to finance infrastructure and other development projects in Malaysia.

The Whale of the title (a reference to what clubs and casinos call their big spenders) is a young Malaysian man called Jho Low, who from an early age loved to host lavish parties and throw lots of money around. On one occasion described in the book, while hanging out with Paris Hilton, Low spent €2m on champagne in a single night (needless to say, this bought more champagne than the whole club-ful of people could drink). But the authors are just as critical of the supposedly reputable banks, auditors and other institutions who were happy to accept and facilitate very dubious-looking deals, as long as a cut of the profits was rolling in their direction.

It's a well-written book, which helps to explain the financial flows just as well as it characterises Low's big-spending habits. One thing I found very curious was the way that Low managed to attract some genuine A-list celebrities to hang out with him. I mean, it's easy to imagine Hilton and the other Z-listers in the book making as much money as possible while they can. But Alicia Keys? Jamie Foxx? The authors explain how Leonardo di Caprio and Martin Scorsese were happy to work with Low because they got complete creative control of their work. (Low's company famously financed The Wolf of Wall Street, which it turns out Warner Bros were not willing to support because they didn't think an R rated film would make its money back. This meant that Scorsese got to crash a real Lamborghini in the opening scene - Warner Bros would have demanded he use a replica. One fascinating snippet is that one of the people who saw through Low very quickly was Jordan Belfort, the subject of Wolf of Wall Street, who after one of Low's parties apparently said "This is a fucking scam ... You wouldn't spend money you'd worked for like that.").

In a strange way, Low is a vacuum at the heart of the book. Other than wanting to be seen and to throw parties, it's hard to know what drove him. Perhaps if he ever stops being a fugitive from justice and comes to trial, we will be able to find out more.

Ordinary folk often get questioned by their banks for small transfers of money. But billionaires are not ordinary. By this point, Low was by far the biggest client that BSI had anywhere in the world, and he was making a lot of people in the bank richer than they ever could have hoped. He was referred to as “Big Boss” in the bank’s Singapore offices, and senior BSI executives would join him for parties in Las Vegas and on yachts. The bank’s senior executives would do all they could to keep Low’s business. Within days of Low’s email*, BSI’s top executives approved the $110 million transfer. “Intra family transfers are not always going to be logical,” a senior BSI banker wrote in response to the compliance officer’s concerns.

*claiming that a transfer that had been routed from one of Low's accounts through his father's account and into another of his accounts was a simple case of a Confucian son trying to give money to his honoured father, who then gave it back.

18wandering_star

7. The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter by Theodora Goss

Well, this was a lot of fun. The Alchemist's Daughter of the title is one Mary Jekyll. Yes, that Jekyll. Or perhaps it refers to one of the other characters - Diana Hyde, Catherine Moreau or Justine Frankenstein, or one Beatrice Rappaccini (who turns out to come from a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne).

As the story starts, Mary Jekyll's mother has just died, leaving Mary penniless. The family lawyer informs her that a certain sum of money has been leaving the accounts each month, for the care of "Hyde". Mary remembers that there is still a bounty on the head of Edward Hyde, a former contact of her father's, and thinks that this might be the solution to her financial worries. She contacts Sherlock Holmes to help her track down Hyde - but instead ends up meeting a number of women who were made monsters by their experimenting creators. (Or are they monsters? This is one of the things the women argue over - for they all chip in to the writing of the story).

In an afterword, Goss says that the germ of the story came from a question that she started asking while working on her PhD dissertation: "Why did so many of the mad scientists in nineteenth-century narratives create, or start creating but then destroy, female monsters?"

Here be monsters.

~~~

MARY: I don’t think that’s the right epigraph for the book.

CATHERINE: Then you write the bloody thing. Honestly, I don’t know why I agreed to do this.

MARY: Because we need money.

CATHERINE: As usual.

Well, this was a lot of fun. The Alchemist's Daughter of the title is one Mary Jekyll. Yes, that Jekyll. Or perhaps it refers to one of the other characters - Diana Hyde, Catherine Moreau or Justine Frankenstein, or one Beatrice Rappaccini (who turns out to come from a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne).

As the story starts, Mary Jekyll's mother has just died, leaving Mary penniless. The family lawyer informs her that a certain sum of money has been leaving the accounts each month, for the care of "Hyde". Mary remembers that there is still a bounty on the head of Edward Hyde, a former contact of her father's, and thinks that this might be the solution to her financial worries. She contacts Sherlock Holmes to help her track down Hyde - but instead ends up meeting a number of women who were made monsters by their experimenting creators. (Or are they monsters? This is one of the things the women argue over - for they all chip in to the writing of the story).

In an afterword, Goss says that the germ of the story came from a question that she started asking while working on her PhD dissertation: "Why did so many of the mad scientists in nineteenth-century narratives create, or start creating but then destroy, female monsters?"

Here be monsters.

~~~

MARY: I don’t think that’s the right epigraph for the book.

CATHERINE: Then you write the bloody thing. Honestly, I don’t know why I agreed to do this.

MARY: Because we need money.

CATHERINE: As usual.

20lisapeet

>16 wandering_star: That book walked the most incredibly fine line between hilarity and heartbreak. I think it helps to have or have had a parent with dementia to laugh at that very black humor, though maybe not necessary.

21wandering_star

>19 dchaikin:, >20 lisapeet: Yes, and sad in a particularly gut-punching way because you aren't expecting it, and also because given the graphic format, the writer doesn't have to find emotional words to describe it - just showing what happened in a very simple and unadorned way.

22wandering_star

8. The Day Lasts More Than A Hundred Years by Chinghiz Aitmatov

It's not uncommon for a book to take you somewhere which is completely removed from your personal reality. But I'm trying to think of another example of a book which has really conveyed a sense of life which is different from anything I've ever even read or heard about. Right now I can't think of one.

The setting of this book is a railway junction in the middle of the Central Asian steppe. Apart from the railway lines crossing each other, there is nothing for hundreds of miles around.

You must have the will to live on the Sarozek junctions—otherwise you perish. The steppe is vast and man is small. The steppe takes no sides; it doesn’t care if you are in trouble or if all is well with you; you have to take the steppe as it is. But a man cannot remain indifferent to the world around him; it worries him and torments him to think that he could be happier somewhere else, and that he is where he is simply through a mistake of fate. Because of this he wears himself out before the great, pitiless steppe and loses his will, just as that accumulator on Shaimerden’s three-wheel motor-bike loses its charge. The owner looks after it, but does not ride it or lend it to anyone else. So the machine stands idle—and that’s all there is to it—soon it won’t start up any more, its starting power is lost. It is the same with a man at a Sarozek junction: he fails to get on with his work, to put down roots in the steppe, to adjust to his surroundings; and then he finds he can’t settle down. Passengers look out from passing trains, shake their heads and ask: “God, how can people live here? Nothing but steppe and camels!” But people who have enough patience can live here. For three years, or four, with an effort. But then they pack up and get as far away as possible. Only two people really put down roots at Boranly-Burannyi—Kazangap and he, Burannyi Yedigei.

At the start of the novel, Yedigei is told that the old man Kazangap has died. Kazangap was already well established at the Sarozek junctions when Yedegei arrived in the 1950s, shattered by the experience of fighting in the war. Yedigei decides that, for all the Soviet teachings, Kazangap should be buried properly, in the old way, and so they set out by tractor and camel to take the body to the cemetery. The story of the journey is interleaved with the stories of Kazangap, Yedigei, and others who have stopped at the junction for a few years, as well as traditional Kazakh myths and legends. Through these, the book touches on the history of the steppe as well as the modern changes, including some of the brutality of Soviet politics (one character ends up in Sarozek because he fought for the Soviet Union in a way which later became seen as politically suspect: the scene in which the apparatchik interrogates Yedigei and twists his words into something incriminating is chilling).

It's not a perfect book. There is a science fiction-y subplot which contains some political critique which I don't think was needed - you get all that you need from the story of the steppe. And there's a love story which reads very differently to a female reader than I think the author intended. But regardless of these criticisms, it's a really interesting read, and one that I think will stay with me.

It's not uncommon for a book to take you somewhere which is completely removed from your personal reality. But I'm trying to think of another example of a book which has really conveyed a sense of life which is different from anything I've ever even read or heard about. Right now I can't think of one.

The setting of this book is a railway junction in the middle of the Central Asian steppe. Apart from the railway lines crossing each other, there is nothing for hundreds of miles around.

You must have the will to live on the Sarozek junctions—otherwise you perish. The steppe is vast and man is small. The steppe takes no sides; it doesn’t care if you are in trouble or if all is well with you; you have to take the steppe as it is. But a man cannot remain indifferent to the world around him; it worries him and torments him to think that he could be happier somewhere else, and that he is where he is simply through a mistake of fate. Because of this he wears himself out before the great, pitiless steppe and loses his will, just as that accumulator on Shaimerden’s three-wheel motor-bike loses its charge. The owner looks after it, but does not ride it or lend it to anyone else. So the machine stands idle—and that’s all there is to it—soon it won’t start up any more, its starting power is lost. It is the same with a man at a Sarozek junction: he fails to get on with his work, to put down roots in the steppe, to adjust to his surroundings; and then he finds he can’t settle down. Passengers look out from passing trains, shake their heads and ask: “God, how can people live here? Nothing but steppe and camels!” But people who have enough patience can live here. For three years, or four, with an effort. But then they pack up and get as far away as possible. Only two people really put down roots at Boranly-Burannyi—Kazangap and he, Burannyi Yedigei.

At the start of the novel, Yedigei is told that the old man Kazangap has died. Kazangap was already well established at the Sarozek junctions when Yedegei arrived in the 1950s, shattered by the experience of fighting in the war. Yedigei decides that, for all the Soviet teachings, Kazangap should be buried properly, in the old way, and so they set out by tractor and camel to take the body to the cemetery. The story of the journey is interleaved with the stories of Kazangap, Yedigei, and others who have stopped at the junction for a few years, as well as traditional Kazakh myths and legends. Through these, the book touches on the history of the steppe as well as the modern changes, including some of the brutality of Soviet politics (one character ends up in Sarozek because he fought for the Soviet Union in a way which later became seen as politically suspect: the scene in which the apparatchik interrogates Yedigei and twists his words into something incriminating is chilling).

It's not a perfect book. There is a science fiction-y subplot which contains some political critique which I don't think was needed - you get all that you need from the story of the steppe. And there's a love story which reads very differently to a female reader than I think the author intended. But regardless of these criticisms, it's a really interesting read, and one that I think will stay with me.

23wandering_star

9. The Meaning of Rice by Michael Booth

A food-focused travelogue of Japan.

I generally avoid funny travelogues because I find they often get their humour by poking fun at the country they are about, rather than seeing a difference and thinking 'how interesting - I wonder why that is'. But a friend recommended this to me, and I did really enjoy it.

Yes, there is a little bit of 'lost in translation' style humour, but Booth is genuinely enthusiastic about Japanese food and admiring of the commitment and hard work of most of the people that he meets - and he shares my obsession with Japanese citruses!

This is followed by a slice of a remarkable fruit, the hyuganatsu, a citrus which – I later look up – spontaneously evolved following the freak pairing of a yuzu and a pomelo in a garden in Miyazaki in the 1820s. The hyuganatsu looks like a self-satisfied yuzu, plump with a beautifully smooth complexion. It is not only blessed with delicious, sweet orange flesh, but also has edible pith which is neither bitter nor astringent like every other citrus fruit I know, but sweet and delicately fragrant. I have a kind of pith phobia but this is fantastic. I add it to my mental list of those obscure local citrus fruits with which Japan abounds, like the dekopon from nearby Kumamoto, the vivacious sudachi (like a kind of mini lime with orange flesh), or the sweet kumquat, the 'kinkan'.

A food-focused travelogue of Japan.

I generally avoid funny travelogues because I find they often get their humour by poking fun at the country they are about, rather than seeing a difference and thinking 'how interesting - I wonder why that is'. But a friend recommended this to me, and I did really enjoy it.

Yes, there is a little bit of 'lost in translation' style humour, but Booth is genuinely enthusiastic about Japanese food and admiring of the commitment and hard work of most of the people that he meets - and he shares my obsession with Japanese citruses!

This is followed by a slice of a remarkable fruit, the hyuganatsu, a citrus which – I later look up – spontaneously evolved following the freak pairing of a yuzu and a pomelo in a garden in Miyazaki in the 1820s. The hyuganatsu looks like a self-satisfied yuzu, plump with a beautifully smooth complexion. It is not only blessed with delicious, sweet orange flesh, but also has edible pith which is neither bitter nor astringent like every other citrus fruit I know, but sweet and delicately fragrant. I have a kind of pith phobia but this is fantastic. I add it to my mental list of those obscure local citrus fruits with which Japan abounds, like the dekopon from nearby Kumamoto, the vivacious sudachi (like a kind of mini lime with orange flesh), or the sweet kumquat, the 'kinkan'.

24wandering_star

10. Mudlarking by Lara Maiklem

An unexpectedly fascinating read about picking up bits of historical detritus on the banks of the Thames. Maiklem is a dedicated 'mudlark', but also someone with a vivid historical imagination - a battered shoe sole is not just a piece of ancient leather, but sends her off thinking about the Elizabethan woman who lost a shoe in the river. She has a knack for conveying the historical fascination, as well as her own delight in spotting the tiniest remains on the rivershore.

And the things that are there to find are remarkable - Iron and Bronze Age weaponry has been found on the banks of the Thames, but according to Maiklem, even a casual search can find Elizabethan remains, if you know what you're looking for. In fact I once had a look at the Thames foreshore myself, on an organised group visit with an experienced mudlark, and we found a lot of Victorian remains and one broken shard of Elizabethan pottery (associated with the Globe Theatre, not far from where we were standing.

But I would never have guessed that it's even possible to find fishbones! (at the shore in front of the old Palace of Greenwich) as well as fabric and wood remains. It turns out that because the mud of the Thames lacks oxygen, it is able to preserve all kinds of things, although the risk is that they fall apart as soon as they are recovered from the mud.

Maiklem has her own instagram @london.mudlark and also a specific instagram account for pictures linked to the book, @laramaiklem_mudlarking. The images there include a Roman bone game counter; a button celebrating the marriage of Charles I; the traces of wooden stakes from a possible Iron Age fish trap. Well worth a look (the instagram and the book)!

Sometimes the smell alone tells me where I am. At the tidal head, the river gives off the soft earthy scent of rotting leaves. On the Isle of Dogs, where the sand is dark with flakes of rust, the smell is hard and metallic. As the sun warms the thick strip of tar on the foreshore at Blackwall, the scent of sailing ships is conjured from the mud, while the oil-soaked sand at Woolwich releases traces of engines and machinery. At Erith and Vauxhall, when the tide is low, the fragrance of the foreshore is peaty and ancient. If time were odorous, it would smell like this.

An unexpectedly fascinating read about picking up bits of historical detritus on the banks of the Thames. Maiklem is a dedicated 'mudlark', but also someone with a vivid historical imagination - a battered shoe sole is not just a piece of ancient leather, but sends her off thinking about the Elizabethan woman who lost a shoe in the river. She has a knack for conveying the historical fascination, as well as her own delight in spotting the tiniest remains on the rivershore.

And the things that are there to find are remarkable - Iron and Bronze Age weaponry has been found on the banks of the Thames, but according to Maiklem, even a casual search can find Elizabethan remains, if you know what you're looking for. In fact I once had a look at the Thames foreshore myself, on an organised group visit with an experienced mudlark, and we found a lot of Victorian remains and one broken shard of Elizabethan pottery (associated with the Globe Theatre, not far from where we were standing.

But I would never have guessed that it's even possible to find fishbones! (at the shore in front of the old Palace of Greenwich) as well as fabric and wood remains. It turns out that because the mud of the Thames lacks oxygen, it is able to preserve all kinds of things, although the risk is that they fall apart as soon as they are recovered from the mud.

Maiklem has her own instagram @london.mudlark and also a specific instagram account for pictures linked to the book, @laramaiklem_mudlarking. The images there include a Roman bone game counter; a button celebrating the marriage of Charles I; the traces of wooden stakes from a possible Iron Age fish trap. Well worth a look (the instagram and the book)!

Sometimes the smell alone tells me where I am. At the tidal head, the river gives off the soft earthy scent of rotting leaves. On the Isle of Dogs, where the sand is dark with flakes of rust, the smell is hard and metallic. As the sun warms the thick strip of tar on the foreshore at Blackwall, the scent of sailing ships is conjured from the mud, while the oil-soaked sand at Woolwich releases traces of engines and machinery. At Erith and Vauxhall, when the tide is low, the fragrance of the foreshore is peaty and ancient. If time were odorous, it would smell like this.

25lisapeet

>24 wandering_star: I was going to say I had another, similar book by Maiklem on the same subject, but a little poking around turned up the fact that Mudlark: In Search of London's Past Along the River Thames was the American/Canadian version of the same book (and entering this gives the touchstone of the edition you mentioned. Amazon, of course, encourages you to buy both, heh. I haven't read it yet, but it appeals to the part of me that's constantly picking things up on my walks and putting them in my coat pockets.

26markon

>22 wandering_star:, >23 wandering_star:, >24 wandering_star: - all of these sound interesting! Mudlark: in search of London's past along the river is the easiest one for me to get hold of, so onto Mt. TBR it goes.

27wandering_star

>25 lisapeet: ...it appeals to the part of me that's constantly picking things up on my walks and putting them in my coat pockets. In that case I think you would definitely enjoy it!

>26 markon: Thank you - I have had a good reading run recently. Continued in

11. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

This is a fragmented memoir about being in an abusive relationship. As such, it's sometimes a tough read (the abuse is mostly emotional/psychological, but occasionally physical). And yet it's the sort of book I want to go around recommending to people. It reminded me a little of Jenny Offill's Dept. of Speculation, a novel about divorce told in a similarly fragmentary manner. I think that works for these two stories because the structure creates a sense of 'how did I end up here', so far from what the narrators were expecting at the start of the relationship.

In the Dream House gives us a series of short images and episodes from the relationship - from the first excitement of lust and love, through the loved one's increasingly unpredictable behaviour, to terrible scenes of rage and jealousy.

You will remember so little about the dinner except that, at the end of it, you want to prolong the evening and so you order tea of all things. You drink it—a mouthful of heat and herb, scorching the roof of your mouth—while trying not to stare at her, trying to be charming and nonchalant while desire gathers in your limbs. Your female crushes were always floating past you, out of reach, but she touches your arm and looks directly at you and you feel like a child buying something with her own money for the first time.

And later:

The next day, after you say good-bye to your friends, you sit in the car in the parking lot as she talks at you—your friends hate me, they’re jealous. An hour later you are still there, your head bent tearily against the window. The new bride walks by and notices you in your car. You see her slow down, her face crimped with puzzlement and concern. You shake your head ever so slightly, and she looks uncertain but mercifully she keeps walking so you can endure your punishment in peace. By the time you’ve wound out of the mountains and gotten back to a freeway, the bite of the fight has sweetened; whiskey unraveled by ice.

Some of the episodes are told in stylistically clever ways, which could have seemed gimmicky except that there is always a reason for it which takes you back to what Machado is saying, and which makes sense emotionally. A short chapter which is a 'lipogram' (without the letter 'e') makes a point about what it's like when there is something huge that you can't talk to anyone about. A chapter in the form of a 'choose your own adventure story' conveys the sense that no matter what Machado did, it wasn't right, and there was no way to break out of the cycle of fights and anger.

>26 markon: Thank you - I have had a good reading run recently. Continued in

11. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

This is a fragmented memoir about being in an abusive relationship. As such, it's sometimes a tough read (the abuse is mostly emotional/psychological, but occasionally physical). And yet it's the sort of book I want to go around recommending to people. It reminded me a little of Jenny Offill's Dept. of Speculation, a novel about divorce told in a similarly fragmentary manner. I think that works for these two stories because the structure creates a sense of 'how did I end up here', so far from what the narrators were expecting at the start of the relationship.

In the Dream House gives us a series of short images and episodes from the relationship - from the first excitement of lust and love, through the loved one's increasingly unpredictable behaviour, to terrible scenes of rage and jealousy.

You will remember so little about the dinner except that, at the end of it, you want to prolong the evening and so you order tea of all things. You drink it—a mouthful of heat and herb, scorching the roof of your mouth—while trying not to stare at her, trying to be charming and nonchalant while desire gathers in your limbs. Your female crushes were always floating past you, out of reach, but she touches your arm and looks directly at you and you feel like a child buying something with her own money for the first time.

And later:

The next day, after you say good-bye to your friends, you sit in the car in the parking lot as she talks at you—your friends hate me, they’re jealous. An hour later you are still there, your head bent tearily against the window. The new bride walks by and notices you in your car. You see her slow down, her face crimped with puzzlement and concern. You shake your head ever so slightly, and she looks uncertain but mercifully she keeps walking so you can endure your punishment in peace. By the time you’ve wound out of the mountains and gotten back to a freeway, the bite of the fight has sweetened; whiskey unraveled by ice.

Some of the episodes are told in stylistically clever ways, which could have seemed gimmicky except that there is always a reason for it which takes you back to what Machado is saying, and which makes sense emotionally. A short chapter which is a 'lipogram' (without the letter 'e') makes a point about what it's like when there is something huge that you can't talk to anyone about. A chapter in the form of a 'choose your own adventure story' conveys the sense that no matter what Machado did, it wasn't right, and there was no way to break out of the cycle of fights and anger.

28wandering_star

After that powerful read I needed something light, so I turned to

12. European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman by Theodora Goss, the sequel to >18 wandering_star:. In this episode, the intrepid and monstrous women of the Athena Club receive an appeal to rescue one Lucinda Van Helsing, apparently incarcerated by her father in a mental institution in Vienna. Along their way they meet more characters from Victorian fiction, from She and Carmilla as well as Dracula.

Early on in this book I wondered if the style would start to become tired - it's very similar to the series opener, with the characters chipping in to interrupt the narrator; both books are LONG; and I'm not sure that any of the main characters are especially three-dimensional. But they are fun, and I am happy to say that I was soon drawn in again. I'll give it a slightly longer break before I read the third in the series though.

“Bea, I’m worried about the two of you going into such a dangerous situation,” said Clarence. “Mrs. Norton, you’ve been describing all this very calmly, but a man who would conduct experiments on his own wife and daughter must be a man entirely without moral qualms. If Beatrice and Cat need my help . . .”

“That’s very kind of you, Clarence,” said Beatrice gently. “But you see, Catherine and I have natural defenses—I have my poison, and Catherine has her agility, her ability to see and smell beyond the human range, her fangs. You would not be protecting us—we would need to protect you.”

“Got it,” said Clarence. He looked a little nonplussed as he cut into his schnitzel.

“But it was chivalrous of you to offer,” she added.

He gave her a swift glance, as though wondering if she were mocking him, but Beatrice simply smiled and continued with her dinner.

12. European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman by Theodora Goss, the sequel to >18 wandering_star:. In this episode, the intrepid and monstrous women of the Athena Club receive an appeal to rescue one Lucinda Van Helsing, apparently incarcerated by her father in a mental institution in Vienna. Along their way they meet more characters from Victorian fiction, from She and Carmilla as well as Dracula.

Early on in this book I wondered if the style would start to become tired - it's very similar to the series opener, with the characters chipping in to interrupt the narrator; both books are LONG; and I'm not sure that any of the main characters are especially three-dimensional. But they are fun, and I am happy to say that I was soon drawn in again. I'll give it a slightly longer break before I read the third in the series though.

“Bea, I’m worried about the two of you going into such a dangerous situation,” said Clarence. “Mrs. Norton, you’ve been describing all this very calmly, but a man who would conduct experiments on his own wife and daughter must be a man entirely without moral qualms. If Beatrice and Cat need my help . . .”

“That’s very kind of you, Clarence,” said Beatrice gently. “But you see, Catherine and I have natural defenses—I have my poison, and Catherine has her agility, her ability to see and smell beyond the human range, her fangs. You would not be protecting us—we would need to protect you.”

“Got it,” said Clarence. He looked a little nonplussed as he cut into his schnitzel.

“But it was chivalrous of you to offer,” she added.

He gave her a swift glance, as though wondering if she were mocking him, but Beatrice simply smiled and continued with her dinner.

29rachbxl

>22 wandering_star: Have you read Aitmatov’s Jamilia? I read it years ago, but I remember clearly being transported to another world in a way that I couldn’t remember another book having done.

30rhian_of_oz

>24 wandering_star: This sounds very interesting and has been added to my wishlist. I love the idea of "hidden treasure" searched for in plain sight.

31wandering_star

>29 rachbxl: I haven't - but I will look out for it now!

32wandering_star

13. The Night Tiger by Yangsze Choo

Malaya, 1931. Ren, a young orphan, working as a houseboy, makes a promise to his dying master, Dr MacFarlane - he will find the master's lost finger and bury it in his grave within 49 days of his death, so that the soul can progress into the afterlife. Fifty miles away, a teenage girl (Ji Lin) accidentally takes something from a man's pocket - a specimen bottle containing the top two joints of a severed finger.

One of the themes in the book is around the Malay myth of the were-tiger, a human who transforms into a tiger to hunt at night. One of the ways that you can spot a were-tiger is that one of their limbs is always damaged. In addition to missing a finger, Dr MacFarlane would say things in his dying delirium about wandering to distant districts, and it would then be reported that someone had been killed by a tiger in that spot. But the tiger attacks don't stop after Ren goes to work for a new master (another British doctor) - and there are a number of other mysterious deaths as well.

I really enjoyed this book at the start. I was drawn into the story quickly and enjoyed the setting, the signs of linkages and parallels between Ren's and Ji Lin's stories, and the interweaving of supernatural events. But, unfortunately, it started to annoy me after a while - both main characters keep going over and over the same ground in a way that started to grate; the way the stories linked together became more laboured; and I kept spotting things which were just wrong for the characters and the time (eg Ji Lin describes lotus seed pods as looking like shower heads - they do, but I can't imagine a girl from a traditional family in 1930s Malaya coming up with that comparison). By the end I was really just skimming to find out what happened.

A gust of wind shivers through the house, banging all the doors simultaneously. To Ren, peering out of the window at the top of the stairs, the trees are a waving green ocean surrounding the bungalow. It’s a ship in a storm, and Ren is the cabin boy peeking out of a porthole. Clutching the windowsill like a life buoy, Ren wonders what secrets lurk in the jungle surrounding them, and if his old master is in fact doomed to roam this vast green expanse forever, trapped in the form of a tiger.

Malaya, 1931. Ren, a young orphan, working as a houseboy, makes a promise to his dying master, Dr MacFarlane - he will find the master's lost finger and bury it in his grave within 49 days of his death, so that the soul can progress into the afterlife. Fifty miles away, a teenage girl (Ji Lin) accidentally takes something from a man's pocket - a specimen bottle containing the top two joints of a severed finger.

One of the themes in the book is around the Malay myth of the were-tiger, a human who transforms into a tiger to hunt at night. One of the ways that you can spot a were-tiger is that one of their limbs is always damaged. In addition to missing a finger, Dr MacFarlane would say things in his dying delirium about wandering to distant districts, and it would then be reported that someone had been killed by a tiger in that spot. But the tiger attacks don't stop after Ren goes to work for a new master (another British doctor) - and there are a number of other mysterious deaths as well.

I really enjoyed this book at the start. I was drawn into the story quickly and enjoyed the setting, the signs of linkages and parallels between Ren's and Ji Lin's stories, and the interweaving of supernatural events. But, unfortunately, it started to annoy me after a while - both main characters keep going over and over the same ground in a way that started to grate; the way the stories linked together became more laboured; and I kept spotting things which were just wrong for the characters and the time (eg Ji Lin describes lotus seed pods as looking like shower heads - they do, but I can't imagine a girl from a traditional family in 1930s Malaya coming up with that comparison). By the end I was really just skimming to find out what happened.

A gust of wind shivers through the house, banging all the doors simultaneously. To Ren, peering out of the window at the top of the stairs, the trees are a waving green ocean surrounding the bungalow. It’s a ship in a storm, and Ren is the cabin boy peeking out of a porthole. Clutching the windowsill like a life buoy, Ren wonders what secrets lurk in the jungle surrounding them, and if his old master is in fact doomed to roam this vast green expanse forever, trapped in the form of a tiger.

33wandering_star

14. Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson

This was exactly what I needed after the slightly frustrating previous read. It's a short but hugely impactful book, which starts with a girl walking down the stairs to her sixteenth birthday celebration. Melody is wearing a dress that once belonged to her mother, Iris - in fact, was bought for Iris' own sixteenth birthday ceremony, but by the time that date came around, Iris was too pregnant with Melody to fit into it. Each chapter then takes us through the story of a different member of the family, and shows how families are made - how an event, an encounter, can echo forward through the years, and how responsibilities to each other are taken up and broken.

When I lean back against my daddy’s chest, I can feel his heart beating. Not the slow beat I’d remembered falling asleep to. This was fast and hard. This was a terrifying pounding in his chest that I had to lift my head away from. Iris was humming as she packed. Every so often, she came over and kissed us both on our cheeks. She was happier than I’d ever seen her.

This was exactly what I needed after the slightly frustrating previous read. It's a short but hugely impactful book, which starts with a girl walking down the stairs to her sixteenth birthday celebration. Melody is wearing a dress that once belonged to her mother, Iris - in fact, was bought for Iris' own sixteenth birthday ceremony, but by the time that date came around, Iris was too pregnant with Melody to fit into it. Each chapter then takes us through the story of a different member of the family, and shows how families are made - how an event, an encounter, can echo forward through the years, and how responsibilities to each other are taken up and broken.

When I lean back against my daddy’s chest, I can feel his heart beating. Not the slow beat I’d remembered falling asleep to. This was fast and hard. This was a terrifying pounding in his chest that I had to lift my head away from. Iris was humming as she packed. Every so often, she came over and kissed us both on our cheeks. She was happier than I’d ever seen her.

34wandering_star

15. Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo

Very enjoyable read, which transplants the basic structure of a heist movie (get the gang together; make a complicated plan; watch the plan unfold - or unravel?) into an urban fantasy genre. The setting is a sort of alternate Golden Age Netherlandish city, in which competing bands of ruffians run different scams and entertainment houses. Kaz Brekker took over one of the smaller gangs and has built it up into a force to be reckoned with. He's still a criminal, though, and he never expected he would be approached by one of the most respectable merchants in the town - but one of the city's enemies appears to have developed a new, much stronger, form of magic, and his wits are needed.

I liked this a lot. I liked the world-building and the different characters and their relationships to each other, as well as the adventure of the story. I would have been happy with less romance but it wasn't egregious.

He hadn’t been sure of the speed of the water, but he knew damn well the numbers were close. Numbers had always been his allies – odds, margins, the art of the wager. But now he had to rely on something more. What god do you serve? Inej had asked him. Whichever will grant me good fortune.

Very enjoyable read, which transplants the basic structure of a heist movie (get the gang together; make a complicated plan; watch the plan unfold - or unravel?) into an urban fantasy genre. The setting is a sort of alternate Golden Age Netherlandish city, in which competing bands of ruffians run different scams and entertainment houses. Kaz Brekker took over one of the smaller gangs and has built it up into a force to be reckoned with. He's still a criminal, though, and he never expected he would be approached by one of the most respectable merchants in the town - but one of the city's enemies appears to have developed a new, much stronger, form of magic, and his wits are needed.

I liked this a lot. I liked the world-building and the different characters and their relationships to each other, as well as the adventure of the story. I would have been happy with less romance but it wasn't egregious.

He hadn’t been sure of the speed of the water, but he knew damn well the numbers were close. Numbers had always been his allies – odds, margins, the art of the wager. But now he had to rely on something more. What god do you serve? Inej had asked him. Whichever will grant me good fortune.

35raton-liseur

>22 wandering_star: An intriguing book. Unfortunetaly, not available in French. I might look out for another book from this author. I have had Il fut un navire blanc/The white steamship in my wishlist for some time. It might be time to decide to read it? Have you heard about this title?

36wandering_star

> 35 I haven't, but it sounds good from the description / reviews. I think I heard about The Day Lasts More Than A Hundred Years on LT, but a long time ago. I don't think I have ever seen the author's name elsewhere.

37sallypursell

wandering_star, you read very interesting books I have heard of nowhere else. Adding to my monstrous TBR pile. Great reviews, too. Thank you.

38raton-liseur

>36 wandering_star: I've heard about this author through the French LT-equivalent, with the title I mentionned. Your review makes me think it might be time to try this new-to-me author! Do you plan to read other books from him?

39wandering_star

I asked a Russian friend of mine about The Day Lasts More Than A Hundred Years. He said: "That book was one of the hits of Perestroyka, everyone read it in the last days of the USSR! It was one of the books that killed the USSR: everyone was inspired and looked for great changes. BTW, the English translation of the title is wrong, because it is too literal, a mechanic translation. 'Vek' in Russian is not only 'a hundred years'. It has poetic connotations like 'eternity'. And Aytmatov's prose was, in fact, poetry. In Russian, his language sounds like a song."

>38 raton-liseur: I would be very interested to read his other books, and Jamilia looks like the best-known. But I am trying not to buy any stuff in 2020, and I don't think his books will be available from the library, so it will have to wait until next year. I would love to hear what you think of The White Steamship though, if you get to it.

>38 raton-liseur: I would be very interested to read his other books, and Jamilia looks like the best-known. But I am trying not to buy any stuff in 2020, and I don't think his books will be available from the library, so it will have to wait until next year. I would love to hear what you think of The White Steamship though, if you get to it.

40wandering_star

16. The Rental Heart and other fairytales by Kirsty Logan

Short stories (often super-short) which convey an awful lot of story in just a few pages. Although there are a couple with a contemporary and naturalistic setting, most of the stories have a fairytale quality. Some are twists on fairytales that we know - a kind of Cinderella story, an encounter with Baba Yaga (which doesn't turn out how you would expect). But more just have a fantastic or magical edge - women make men out of paper, or rent clockwork ones; a woman starts to eat light, a man to eat words. There's a lot of intense love and lust.

Because the stories were so short I ate them like a box of chocolates, but unusually they have grown in my memory since I finished reading them.

They made it seem so complicated, but it wasn’t really. The hearts just clipped in, and as long as you remembered to close yourself up tightly, then they could tick away for years. Decades, probably. The problems come when the hearts get old and scratched: shreds of past loves get caught in the dents, and they’re tricky to rinse out.

PS: I realised when I got to the story "The Gracekeepers" that I'd started reading a novel by Logan, going by the same name and presumably an expansion of the story. I abandoned The Gracekeepers part way through but now I think I will dig it out and have another go.

Short stories (often super-short) which convey an awful lot of story in just a few pages. Although there are a couple with a contemporary and naturalistic setting, most of the stories have a fairytale quality. Some are twists on fairytales that we know - a kind of Cinderella story, an encounter with Baba Yaga (which doesn't turn out how you would expect). But more just have a fantastic or magical edge - women make men out of paper, or rent clockwork ones; a woman starts to eat light, a man to eat words. There's a lot of intense love and lust.

Because the stories were so short I ate them like a box of chocolates, but unusually they have grown in my memory since I finished reading them.

They made it seem so complicated, but it wasn’t really. The hearts just clipped in, and as long as you remembered to close yourself up tightly, then they could tick away for years. Decades, probably. The problems come when the hearts get old and scratched: shreds of past loves get caught in the dents, and they’re tricky to rinse out.

PS: I realised when I got to the story "The Gracekeepers" that I'd started reading a novel by Logan, going by the same name and presumably an expansion of the story. I abandoned The Gracekeepers part way through but now I think I will dig it out and have another go.

41wandering_star

17. Me by Elton John

I noted the reviews when this came out, but only became interested to read it after seeing the excellent biopic Rocketman. I enjoyed the film but didn't know much about Elton John's life so I thought I would give the book a go.

Towards the end of the book, he writes about helping the young star of Rocketman prepare for the role.

I’d invited Taron to Woodside and chatted with him over a takeaway curry, and I let him read some of the old diaries I’d kept in the early seventies to give him a sense of what my life was like then. Those diaries are inadvertently hilarious. I wrote down everything in this incredibly matter-of-fact way, which just makes it seem even more preposterous. ‘Got up. Tidied the house. Watched football on TV. Wrote “Candle In The Wind”. Went to London. Bought Rolls-Royce. Ringo Starr came for dinner.’ I suppose I was trying to normalize what was happening to me, despite the fact that what was happening to me clearly wasn’t normal at all.

That extract I think gives you a pretty good sense of what the book is like. All sorts of crazy experiences, told with a good dollop of self-deprecation, distance and humour. Cleverly, Elton doesn't try to to hide the more notorious elements of his personality - he acknowledges that he's sometimes a shit and has a terrible temper - but he does this in such a charming way and crucially, without giving many details of those on the receiving end - that the reader is very much inclined to forgive him.

I enjoyed this hugely.

I noted the reviews when this came out, but only became interested to read it after seeing the excellent biopic Rocketman. I enjoyed the film but didn't know much about Elton John's life so I thought I would give the book a go.

Towards the end of the book, he writes about helping the young star of Rocketman prepare for the role.

I’d invited Taron to Woodside and chatted with him over a takeaway curry, and I let him read some of the old diaries I’d kept in the early seventies to give him a sense of what my life was like then. Those diaries are inadvertently hilarious. I wrote down everything in this incredibly matter-of-fact way, which just makes it seem even more preposterous. ‘Got up. Tidied the house. Watched football on TV. Wrote “Candle In The Wind”. Went to London. Bought Rolls-Royce. Ringo Starr came for dinner.’ I suppose I was trying to normalize what was happening to me, despite the fact that what was happening to me clearly wasn’t normal at all.

That extract I think gives you a pretty good sense of what the book is like. All sorts of crazy experiences, told with a good dollop of self-deprecation, distance and humour. Cleverly, Elton doesn't try to to hide the more notorious elements of his personality - he acknowledges that he's sometimes a shit and has a terrible temper - but he does this in such a charming way and crucially, without giving many details of those on the receiving end - that the reader is very much inclined to forgive him.

I enjoyed this hugely.

42wandering_star

18. The Snake Stone by Jason Goodwin

Second in the series of detective stories set in 1830s Istanbul, with Yashim (former imperial eunuch) as the detective. I found the details of the crime story massively confusing and I'm still not sure I understand who did what to who! But despite that I enjoyed the book, especially because of the setting - I felt that I got a real sense of the late Ottoman period, as the Empire gradually became more Westernised, and the melting pot of different cultures which Istanbul must have been at the time.

Second in the series of detective stories set in 1830s Istanbul, with Yashim (former imperial eunuch) as the detective. I found the details of the crime story massively confusing and I'm still not sure I understand who did what to who! But despite that I enjoyed the book, especially because of the setting - I felt that I got a real sense of the late Ottoman period, as the Empire gradually became more Westernised, and the melting pot of different cultures which Istanbul must have been at the time.

43wandering_star

19. Dreamsnake by Vonda McIntyre

This is a difficult review to start because giving a synopsis of the story doesn't do anything to explain what it's like to read this book or what I enjoyed about it.

However, I guess a synopsis is where I should start.

Sometime in the distant future, after a destructive nuclear war, the world has become atomised into a few small and distinct communities, who live in tiny fertile valleys spread across a vast desertscape. One of the communities is a community of healers, whose most powerful medicine comes from the mysterious dreamsnake. But their ability to heal is limited by the fact that dreamsnakes are rare, and have never been successfully bred in captivity.

Snake is a young healer who is doing her period of apprenticeship among the other communities. When her dreamsnake is killed, she can't bear the thought of returning to her home having lost one of the precious creatures, so she sets out to find where they come from, a journey which takes her through various different communities within the land.

It's this journey, and in particular seeing the different communities, which I most enjoyed. I love sci fi that does good world-building, and I felt that each episode in a different community could almost have been a book in itself. And from the social attitudes, I would never have guessed that this was first published in 1978. It seems like a book ahead of its time.

Snake drew her knees up under her chin. Against the black rocks, the rattlesnake’s patterns were almost as conspicuous as Mist’s albino scales. Neither serpents nor humans nor anything else left alive on earth had yet adapted to their world as it existed now.

This is a difficult review to start because giving a synopsis of the story doesn't do anything to explain what it's like to read this book or what I enjoyed about it.

However, I guess a synopsis is where I should start.

Sometime in the distant future, after a destructive nuclear war, the world has become atomised into a few small and distinct communities, who live in tiny fertile valleys spread across a vast desertscape. One of the communities is a community of healers, whose most powerful medicine comes from the mysterious dreamsnake. But their ability to heal is limited by the fact that dreamsnakes are rare, and have never been successfully bred in captivity.

Snake is a young healer who is doing her period of apprenticeship among the other communities. When her dreamsnake is killed, she can't bear the thought of returning to her home having lost one of the precious creatures, so she sets out to find where they come from, a journey which takes her through various different communities within the land.

It's this journey, and in particular seeing the different communities, which I most enjoyed. I love sci fi that does good world-building, and I felt that each episode in a different community could almost have been a book in itself. And from the social attitudes, I would never have guessed that this was first published in 1978. It seems like a book ahead of its time.

Snake drew her knees up under her chin. Against the black rocks, the rattlesnake’s patterns were almost as conspicuous as Mist’s albino scales. Neither serpents nor humans nor anything else left alive on earth had yet adapted to their world as it existed now.

44wandering_star

20. Viking Britain by Tom Williams