thorold hopes to read fewer books in Q3

Dit is een voortzetting van het onderwerp thorold looks for the horse in Q2.

DiscussieClub Read 2020

Sluit je aan bij LibraryThing om te posten.

2thorold

Welcome to my Q3 reading thread!

Q2 looks like being something of a record quarter in terms of the number of books I finished. For obvious reasons, I had a lot more time to read than I really wanted — I hope I made good use of it! I certainly read some good books, but still, I'm hoping that I'll be spending more time in Q3 out and about, and less reading, even if there's no chance of major travel. Fingers crossed!

Q2 looks like being something of a record quarter in terms of the number of books I finished. For obvious reasons, I had a lot more time to read than I really wanted — I hope I made good use of it! I certainly read some good books, but still, I'm hoping that I'll be spending more time in Q3 out and about, and less reading, even if there's no chance of major travel. Fingers crossed!

3thorold

Q2 stats:

I finished 89 books in Q2 (70 in Q1). Not quite a book a day, but perilously close, especially given that some of them were pretty long.

Author gender: M 61, F 27, n/a 1 (69% M; Q1: 71% M)

Language: EN 69, NL 2, FR 8, DE 4, ES 3, IT 3 (78% EN; Q1 54% EN) — all the books from English-speaking Africa skewing the numbers here!

34 books (38%) were linked to the "Southern Africa" theme read (Q1: 28% "far right" theme)

Publication dates from 1887 to 2020, mean 1976, median 1984; 11 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 1, physical books from the TBR 54(!), physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 3, audiobooks 12, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 14 — 61% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, 43% library) — spot the lockdown effect!

77 unique first authors (1.15 books/author; Q1 1.11)

By gender: M 55, F 21, n/a 1 (71% M; Q1 71% M)

By main country: UK 18, NL 2, US 9, FR 3, DE 2, and Southern Africa: South Africa 20, Zimbabwe 4, Botswana 1, Lesotho 1, Namibia 1

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

Despite "freshening" over half the TBR, I only reduced the average days-per-book of those waiting from 1180 to 1087. Browsing from the top is still the favoured mode!

I finished 89 books in Q2 (70 in Q1). Not quite a book a day, but perilously close, especially given that some of them were pretty long.

Author gender: M 61, F 27, n/a 1 (69% M; Q1: 71% M)

Language: EN 69, NL 2, FR 8, DE 4, ES 3, IT 3 (78% EN; Q1 54% EN) — all the books from English-speaking Africa skewing the numbers here!

34 books (38%) were linked to the "Southern Africa" theme read (Q1: 28% "far right" theme)

Publication dates from 1887 to 2020, mean 1976, median 1984; 11 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 1, physical books from the TBR 54(!), physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 3, audiobooks 12, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 14 — 61% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, 43% library) — spot the lockdown effect!

77 unique first authors (1.15 books/author; Q1 1.11)

By gender: M 55, F 21, n/a 1 (71% M; Q1 71% M)

By main country: UK 18, NL 2, US 9, FR 3, DE 2, and Southern Africa: South Africa 20, Zimbabwe 4, Botswana 1, Lesotho 1, Namibia 1

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

Despite "freshening" over half the TBR, I only reduced the average days-per-book of those waiting from 1180 to 1087. Browsing from the top is still the favoured mode!

4thorold

Q2 highlights, Q3 goals

Things that really stand out in Q2:

- The Zolathon — since the start of 2018 I've been on a mission to read through the twenty Rougon-Macquart novels in publication order, in French. I finished yesterday with Le Docteur Pascal. I'd read all the really famous ones before, some in translation, some in French, but it was a long time ago, and it was really good to be able to put them in context. I still want to spend some time reading about Zola himself and the background to the books.

- Pilgrimage 3 and 4 — I read the first two volumes of Dorothy Richardson's overlooked modernist masterpiece in Q1 and completed the project in Q2. Very interesting, and probably a book I'll come back to: a lot of insight into a fascinating period from an unusual perspective, and a very individual style.

- Southern Africa — this was a theme read for Reading Globally. I'd dipped into enough writing from the region previously to know that there is a lot of interesting material out there, but after three months and 37 books (counting three from Q1) I still feel I've barely scraped the surface. It was especially good to get around to early classics like Chaka and Mhudi (when I was a postgrad I shared a house with someone who was writing a thesis on Chaka, so it's about time!). The books that impressed me most were probably those of Alex la Guma and Es'kia Mphahlele, from the mid-20th century, but I'm certainly also going to look for more Ivan Vladislavić and Zakes Mda as well. I still have a few SA books on the pile, and a separate pile of borrowed ones to read, so that isn't over yet!

- Communist propaganda — looking for apartheid-era books by South Africans, I accidentally came across some books from Seven Seas Books, an East Berlin publisher of English-language books in the sixties and seventies. When I investigated further, this led me to some left-wing British, American and Australian writers I didn't know about, as well as to some classics of DDR literature, like the collective-farm tragedy Ole Bienkopp. And indirectly to the oddest book of Q2, ... und Du, Frau an der Werkbank : die DDR in den 50er Jahren, a survey of how DDR magazines in the fifties depicted working women.

- Lesser landmarks

Lost children archive — a book that took me by surprise, there's far more to it than the single-issue story I was expecting.

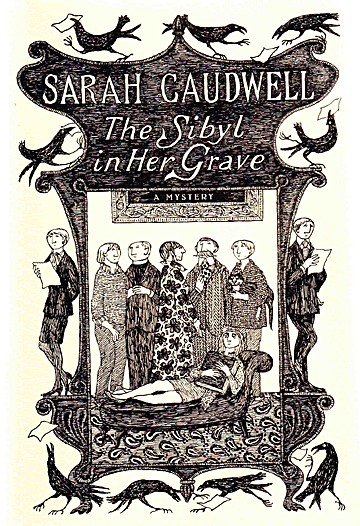

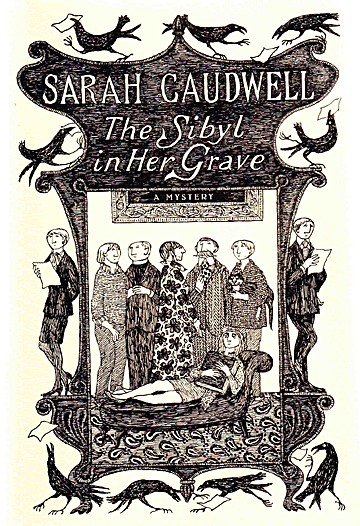

Sarah Caudwell — funny legal mystery stories from the eighties, which I somehow never noticed at the time. I've still got two left to read.

Ireland — A totally unplanned sub-theme! I enjoyed a couple of Anne Enright novels and a Colm Tóibín, and even managed to sneak Dervla Murphy into the Southern Africa topic.

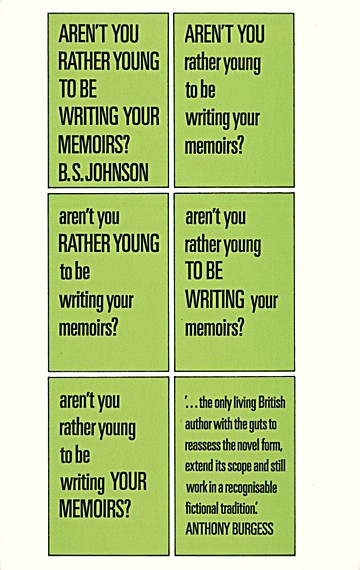

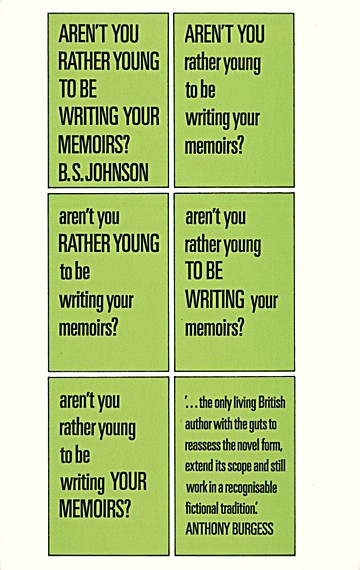

Q2 was also the quarter in which I finally cleared some real monsters from the TBR, including The Quincunx (nothing special), Meneer Beerta (excellent, I want to carry on with this series), and the last few leftovers from my explorations of offbeat British writers B S Johnson and Christine Brooke-Rose.

- Aims for Q3

No "big" projects at the moment.

- The reading Globally theme read for Q3 is "travelling the TBR road", something I'll certainly be doing!

- I've got quite a bit of South Africa and a couple more hefty DDR-classics to finish off from Q2

- I'm leaning towards having a go at the next volume of Voskuil's monster.

- There hasn't been much poetry going on lately, apart from Mark Doty's Whitman book: I need to do something about that

Things that really stand out in Q2:

- The Zolathon — since the start of 2018 I've been on a mission to read through the twenty Rougon-Macquart novels in publication order, in French. I finished yesterday with Le Docteur Pascal. I'd read all the really famous ones before, some in translation, some in French, but it was a long time ago, and it was really good to be able to put them in context. I still want to spend some time reading about Zola himself and the background to the books.

- Pilgrimage 3 and 4 — I read the first two volumes of Dorothy Richardson's overlooked modernist masterpiece in Q1 and completed the project in Q2. Very interesting, and probably a book I'll come back to: a lot of insight into a fascinating period from an unusual perspective, and a very individual style.

- Southern Africa — this was a theme read for Reading Globally. I'd dipped into enough writing from the region previously to know that there is a lot of interesting material out there, but after three months and 37 books (counting three from Q1) I still feel I've barely scraped the surface. It was especially good to get around to early classics like Chaka and Mhudi (when I was a postgrad I shared a house with someone who was writing a thesis on Chaka, so it's about time!). The books that impressed me most were probably those of Alex la Guma and Es'kia Mphahlele, from the mid-20th century, but I'm certainly also going to look for more Ivan Vladislavić and Zakes Mda as well. I still have a few SA books on the pile, and a separate pile of borrowed ones to read, so that isn't over yet!

- Communist propaganda — looking for apartheid-era books by South Africans, I accidentally came across some books from Seven Seas Books, an East Berlin publisher of English-language books in the sixties and seventies. When I investigated further, this led me to some left-wing British, American and Australian writers I didn't know about, as well as to some classics of DDR literature, like the collective-farm tragedy Ole Bienkopp. And indirectly to the oddest book of Q2, ... und Du, Frau an der Werkbank : die DDR in den 50er Jahren, a survey of how DDR magazines in the fifties depicted working women.

- Lesser landmarks

Lost children archive — a book that took me by surprise, there's far more to it than the single-issue story I was expecting.

Sarah Caudwell — funny legal mystery stories from the eighties, which I somehow never noticed at the time. I've still got two left to read.

Ireland — A totally unplanned sub-theme! I enjoyed a couple of Anne Enright novels and a Colm Tóibín, and even managed to sneak Dervla Murphy into the Southern Africa topic.

Q2 was also the quarter in which I finally cleared some real monsters from the TBR, including The Quincunx (nothing special), Meneer Beerta (excellent, I want to carry on with this series), and the last few leftovers from my explorations of offbeat British writers B S Johnson and Christine Brooke-Rose.

- Aims for Q3

No "big" projects at the moment.

- The reading Globally theme read for Q3 is "travelling the TBR road", something I'll certainly be doing!

- I've got quite a bit of South Africa and a couple more hefty DDR-classics to finish off from Q2

- I'm leaning towards having a go at the next volume of Voskuil's monster.

- There hasn't been much poetry going on lately, apart from Mark Doty's Whitman book: I need to do something about that

5thorold

I usually have one or two of the free books from the Dutch book promotion week (Boekenweek) on my TBR — quite apart from recent ones that I've got in the normal way by buying books during the promotion week, the older ones frequently turn up in little free libraries. Because they are only about 100 pages long, they're great for quick in-between reads, and as a way of finding out about interesting Dutch writers. This is the 1962 gift, by Anton Koolhaas, a well-known journalist and reviewer who produced many collections of animal stories in his time:

Een schot in de lucht (1962) by Anton Koolhaas (Netherlands, 1912-1992); illustrations by Metten Koornstra, Annemieke van Ogtrop, Lotte Ruting, Theo Blom and Peter Vos

This turns out to be a form I've never come across before: a picaresque novella! A series of otherwise unrelated scenes are linked by the presence of a randomly-wandering dog, as it abandons the country-house where it is well looked after but not loved, visits a farm, wanders into town, witnesses a road accident, spends some time hanging about a station, and ends up with a depressed and lonely railwayman in his signal-box.

We catch glimpses of complex human and animal stories as the dog passes by, but the dog has always moved on before we get a chance to examine them in detail and see how they are going to end. Both from the animal and the human points of view, the view of life is a fairly bleak one, and definitely meant for adult readers: more Richard Adams than Beatrix Potter, but always with an ironic twist. The animals behave in naturalistic ways, but they have a kind of anthropomorphised consciousness that the narrator can see into. Not the sort of thing I often read, but interesting, and quite nicely done.

Fun, too, to be back in the world of 1962, with lever-frame signal boxes in the middle of nowhere with telegraph bells and buzzers, coal trains, and a station buffet with revolving doors...

In keeping with the picaresque plot, the committee commissioned no fewer than five artists to illustrate a chapter each with line-drawings. Lots of variety in style, as you would expect, and also in form: four of the drawings are double-page spreads, others are little sketches of dogs, birds and flies that pepper the margins. Fun!

Een schot in de lucht (1962) by Anton Koolhaas (Netherlands, 1912-1992); illustrations by Metten Koornstra, Annemieke van Ogtrop, Lotte Ruting, Theo Blom and Peter Vos

This turns out to be a form I've never come across before: a picaresque novella! A series of otherwise unrelated scenes are linked by the presence of a randomly-wandering dog, as it abandons the country-house where it is well looked after but not loved, visits a farm, wanders into town, witnesses a road accident, spends some time hanging about a station, and ends up with a depressed and lonely railwayman in his signal-box.

We catch glimpses of complex human and animal stories as the dog passes by, but the dog has always moved on before we get a chance to examine them in detail and see how they are going to end. Both from the animal and the human points of view, the view of life is a fairly bleak one, and definitely meant for adult readers: more Richard Adams than Beatrix Potter, but always with an ironic twist. The animals behave in naturalistic ways, but they have a kind of anthropomorphised consciousness that the narrator can see into. Not the sort of thing I often read, but interesting, and quite nicely done.

Fun, too, to be back in the world of 1962, with lever-frame signal boxes in the middle of nowhere with telegraph bells and buzzers, coal trains, and a station buffet with revolving doors...

In keeping with the picaresque plot, the committee commissioned no fewer than five artists to illustrate a chapter each with line-drawings. Lots of variety in style, as you would expect, and also in form: four of the drawings are double-page spreads, others are little sketches of dogs, birds and flies that pepper the margins. Fun!

6thorold

Still a few South Africans on the pile... This is another early book by a black South African writer:

The black people and whence they came : a Zulu view (Abantu Abamnyama, Zulu 1922; English 1979) by Magema M Fuze (South Africa, 1840-1922), translated by Harry Lugg (1882-1978), edited by A T Cope

Magema Magwaza Fuze came from an important Zulu family. He was educated by Bishop Colenso at the famous Ekukhanyeni mission station, trained as a compositor and printer (like Sol Plaatje) and remained in Colenso's circle, becoming a teacher and a notable early writer and journalist in the Zulu language. He met Cetshwayo a number of times, and acted as tutor to Dinuzulu's family during their exile on Saint Helena.

Fuze's book Abantu Abamnyama, written around 1900 and eventually published with the help of contributions from Zulu and European supporters shortly before his death in 1922, is usually cited as the first major original work to be published in the Zulu language. It seems to have been conceived mostly as a permanent record of the oral knowledge of tribal history that had been handed down to him in his youth. There's a fairly speculative general introduction about the early history of black Africans, interesting more as a record of popular received opinion at the time than anything else. It also gives an interesting insight into the sort of speculative discussions that must have gone on in Colenso's liberal Anglican circles: Fuze demonstrates logically that Adam and Eve must have been black, for example, and tells us about one particular tribe that is said to have given up agriculture and evolved into baboons, in an odd bit of reverse-Darwinism.

When he comes to the Zulu and their direct ancestors, Fuze speaks with much more conviction, and we get pages and pages of genealogies which must be gold-dust for specialists, if rather dry for the rest of us. But there's also plenty of interesting information about traditional customs and their variations, and some entertaining anecdotes explaining where particular names come from. From Shaka onwards, we get a detailed historical account from the Zulu point of view: as an enlightened Christian, Fuze obviously finds it necessary to disapprove of the excesses committed by Shaka and Cetshwayo, but he's nowhere near as critical as non-Zulus like Mofolo and Plaatje. And of course, when we get to Cetshwayo and Dinuzulu, Fuze is talking about events and people he was very close to himself, so it's a very interesting story, if a slightly rambling one. Zulus are thoroughly blamed for their many internecine wars, but wars between Zulus and non-Zulus are always somehow the fault of the outsiders.

This English translation was made in the 1970s for the University of Natal by Harry Lugg, a former Commissioner for Native Affairs in Natal, who had known Fuze well (and was in his nineties when he did the translation). He rearranged Fuze's rambling text slightly to give a more logical sequence, and the text is peppered with Lugg's comments on the words used in the Zulu original as well as the editor's notes on the historical background, so it's not the easiest of books to read. To add insult to injury, it's printed like a thesis, as a photographic reduction of the typescript (the expert compositor Fuze would not have been amused). But there's a nice 1970s look and smell to it.

The black people and whence they came : a Zulu view (Abantu Abamnyama, Zulu 1922; English 1979) by Magema M Fuze (South Africa, 1840-1922), translated by Harry Lugg (1882-1978), edited by A T Cope

Magema Magwaza Fuze came from an important Zulu family. He was educated by Bishop Colenso at the famous Ekukhanyeni mission station, trained as a compositor and printer (like Sol Plaatje) and remained in Colenso's circle, becoming a teacher and a notable early writer and journalist in the Zulu language. He met Cetshwayo a number of times, and acted as tutor to Dinuzulu's family during their exile on Saint Helena.

Fuze's book Abantu Abamnyama, written around 1900 and eventually published with the help of contributions from Zulu and European supporters shortly before his death in 1922, is usually cited as the first major original work to be published in the Zulu language. It seems to have been conceived mostly as a permanent record of the oral knowledge of tribal history that had been handed down to him in his youth. There's a fairly speculative general introduction about the early history of black Africans, interesting more as a record of popular received opinion at the time than anything else. It also gives an interesting insight into the sort of speculative discussions that must have gone on in Colenso's liberal Anglican circles: Fuze demonstrates logically that Adam and Eve must have been black, for example, and tells us about one particular tribe that is said to have given up agriculture and evolved into baboons, in an odd bit of reverse-Darwinism.

When he comes to the Zulu and their direct ancestors, Fuze speaks with much more conviction, and we get pages and pages of genealogies which must be gold-dust for specialists, if rather dry for the rest of us. But there's also plenty of interesting information about traditional customs and their variations, and some entertaining anecdotes explaining where particular names come from. From Shaka onwards, we get a detailed historical account from the Zulu point of view: as an enlightened Christian, Fuze obviously finds it necessary to disapprove of the excesses committed by Shaka and Cetshwayo, but he's nowhere near as critical as non-Zulus like Mofolo and Plaatje. And of course, when we get to Cetshwayo and Dinuzulu, Fuze is talking about events and people he was very close to himself, so it's a very interesting story, if a slightly rambling one. Zulus are thoroughly blamed for their many internecine wars, but wars between Zulus and non-Zulus are always somehow the fault of the outsiders.

This English translation was made in the 1970s for the University of Natal by Harry Lugg, a former Commissioner for Native Affairs in Natal, who had known Fuze well (and was in his nineties when he did the translation). He rearranged Fuze's rambling text slightly to give a more logical sequence, and the text is peppered with Lugg's comments on the words used in the Zulu original as well as the editor's notes on the historical background, so it's not the easiest of books to read. To add insult to injury, it's printed like a thesis, as a photographic reduction of the typescript (the expert compositor Fuze would not have been amused). But there's a nice 1970s look and smell to it.

7thorold

And a more mainstream history book that's been on the TBR pile since 2018. I've been circling around Frederick for a while, with books by Blanning and Roy Porter on the eighteenth century, Christopher Clark on Prussia, Norman Davies on Poland, and most recently Boswell on the grand tour meeting Voltaire but failing to meet Frederick. Definitely time to read a proper biography:

Frederick the Great : King of Prussia (2015) by T C W Blanning (UK, 1942- )

Frederick the Great is one of those endlessly contradictory figures, who can be roped in to justify almost any theory of history: enlightened authoritarian, populist aesthete, atheist champion of the "protestant cause", German nationalist icon who despised the German language and its culture, the military genius who lost as many battles as he won, and the man who launched the unprovoked invasion of a neighbouring territory three months after publishing an anti-war book.

Blanning's strategy in this fascinating biography seems to be to embrace the contradictions without taking sides, as far as that's possible, and to look into the separate strains in Frederick's political and personal situation that were pushing him in these opposing directions. Key, of course, is Frederick's terrible relationship with his father: ruthlessly bullied up to the moment Frederick William died, he enthusiastically took up everything his father hated: art, music, clothes, porcelain, philosophy, free-thinking (and conversely, he took against hunting, drinking, and heterosexuality...). But, thanks to his father's philistinism, he had a very poor education, with all kinds of gaps that couldn't easily be filled later in life. And, in an age when great powers like France and Austria were virtually bankrupt, he had inherited a huge, low-mileage army and enormous piles of hard cash that the miserly Frederick William hadn't had any interest in spending. It would have needed a lot of willpower not to start at least a small war, and the strategically vital Austrian province of Silesia seemed to be there for the taking...

We are led fairly efficiently through the many conflicts of the Silesian wars, the Seven Years War, and the Bavarian Succession, although it's pretty clear that Blanning's first interest is not military history: he conscientiously gives us a sketch-map of each of the important battles, but rarely describes them in the sort of detail that would make a map useful. The diplomacy and strategic manoeuvring in the background is much more fascinating than the battlefield action, but it does become clear that Frederick was better at emotional leadership than at battlefield tactics. When he won a battle he got all the credit because he was so much admired by his subordinates (if not by his fellow-generals). And when he didn't win, he often managed to limit the damage by moving more quickly and decisively after the battle than his opponents.

The more interesting part of the book deals with cultural and social issues. The interesting puzzle of how Berlin-Potsdam failed to become a really important musical centre, despite having a ruler who was a talented and enthusiastic musician. Mannheim and Vienna were the real musical hotspots of the time, with London not far behind. Blanning gives a lot of the blame for that to Frederick's micro-management, and to his tastes that were frozen somewhere in the 1730s. Innovative musicians would have been permanently at war with him, and word soon got around that he didn't take kindly to anyone who wanted to move on to a better-paid post elsewhere. If you were a talented soprano (or a French philosophe) you might well find a Berlin Wall restricting your movements well before 1960. So he was left with competent but not top-flight musicians, like J J Quantz and C P E Bach.

Language is the really odd thing: Frederick seems to have treated his native language in much the same way that 19th century colonial administrators thought of African and Asian languages: useful for giving orders and condescending to the locals, but scarcely a medium for high culture. French was insisted on for official business, and was the language Frederick wrote his many books and poems in — one of the causes of his famous row with Voltaire was his expectation that the great man would be willing to act as his spelling-checker. At a moment when all Europe was rushing out to buy copies of Werther (and the fancy-dress to go with it), Frederick was publishing a pamphlet arguing that it was impossible for German culture to match the achievements of French and Italian. Lessing, the most distinguished Prussian writer of the time, whom Frederick took even less notice of than he did of Goethe, charitably suggested that Frederick's highly-publicised contempt actually encouraged German writers to try harder.

Of course, the thing we really want from a 21st century biography of Frederick is to follow him into the bedroom! Blanning admits that there's no likelihood now that we will ever get conclusive information about Frederick's real sexual preferences from someone who was there at the time, but decides on the basis of the huge amount of circumstantial evidence (from the all-male parties and homoerotic artworks at Sanssouci to Frederick's abandonment of the pretence of living with his wife the moment his father was out of the way) that it's silly to try to represent him as heterosexual, as many earlier historians have done.

Very readable and interesting biography.

Frederick the Great : King of Prussia (2015) by T C W Blanning (UK, 1942- )

Frederick the Great is one of those endlessly contradictory figures, who can be roped in to justify almost any theory of history: enlightened authoritarian, populist aesthete, atheist champion of the "protestant cause", German nationalist icon who despised the German language and its culture, the military genius who lost as many battles as he won, and the man who launched the unprovoked invasion of a neighbouring territory three months after publishing an anti-war book.

Blanning's strategy in this fascinating biography seems to be to embrace the contradictions without taking sides, as far as that's possible, and to look into the separate strains in Frederick's political and personal situation that were pushing him in these opposing directions. Key, of course, is Frederick's terrible relationship with his father: ruthlessly bullied up to the moment Frederick William died, he enthusiastically took up everything his father hated: art, music, clothes, porcelain, philosophy, free-thinking (and conversely, he took against hunting, drinking, and heterosexuality...). But, thanks to his father's philistinism, he had a very poor education, with all kinds of gaps that couldn't easily be filled later in life. And, in an age when great powers like France and Austria were virtually bankrupt, he had inherited a huge, low-mileage army and enormous piles of hard cash that the miserly Frederick William hadn't had any interest in spending. It would have needed a lot of willpower not to start at least a small war, and the strategically vital Austrian province of Silesia seemed to be there for the taking...

We are led fairly efficiently through the many conflicts of the Silesian wars, the Seven Years War, and the Bavarian Succession, although it's pretty clear that Blanning's first interest is not military history: he conscientiously gives us a sketch-map of each of the important battles, but rarely describes them in the sort of detail that would make a map useful. The diplomacy and strategic manoeuvring in the background is much more fascinating than the battlefield action, but it does become clear that Frederick was better at emotional leadership than at battlefield tactics. When he won a battle he got all the credit because he was so much admired by his subordinates (if not by his fellow-generals). And when he didn't win, he often managed to limit the damage by moving more quickly and decisively after the battle than his opponents.

The more interesting part of the book deals with cultural and social issues. The interesting puzzle of how Berlin-Potsdam failed to become a really important musical centre, despite having a ruler who was a talented and enthusiastic musician. Mannheim and Vienna were the real musical hotspots of the time, with London not far behind. Blanning gives a lot of the blame for that to Frederick's micro-management, and to his tastes that were frozen somewhere in the 1730s. Innovative musicians would have been permanently at war with him, and word soon got around that he didn't take kindly to anyone who wanted to move on to a better-paid post elsewhere. If you were a talented soprano (or a French philosophe) you might well find a Berlin Wall restricting your movements well before 1960. So he was left with competent but not top-flight musicians, like J J Quantz and C P E Bach.

Language is the really odd thing: Frederick seems to have treated his native language in much the same way that 19th century colonial administrators thought of African and Asian languages: useful for giving orders and condescending to the locals, but scarcely a medium for high culture. French was insisted on for official business, and was the language Frederick wrote his many books and poems in — one of the causes of his famous row with Voltaire was his expectation that the great man would be willing to act as his spelling-checker. At a moment when all Europe was rushing out to buy copies of Werther (and the fancy-dress to go with it), Frederick was publishing a pamphlet arguing that it was impossible for German culture to match the achievements of French and Italian. Lessing, the most distinguished Prussian writer of the time, whom Frederick took even less notice of than he did of Goethe, charitably suggested that Frederick's highly-publicised contempt actually encouraged German writers to try harder.

Of course, the thing we really want from a 21st century biography of Frederick is to follow him into the bedroom! Blanning admits that there's no likelihood now that we will ever get conclusive information about Frederick's real sexual preferences from someone who was there at the time, but decides on the basis of the huge amount of circumstantial evidence (from the all-male parties and homoerotic artworks at Sanssouci to Frederick's abandonment of the pretence of living with his wife the moment his father was out of the way) that it's silly to try to represent him as heterosexual, as many earlier historians have done.

Very readable and interesting biography.

8thorold

This one popped up as "contemporary fiction for you" in my Scribd recommendations — roughly contemporary with me, I suppose, although that's probably not what they meant...

Anyway, I haven't read it since I was about seventeen, when I had to read it more or less clandestinely, not so much because anyone was afraid that I might get the wrong sort of ideas, but rather because it would have provoked comments from parents and teachers about "that terrible American woman who ruined Ted Hughes's life" ("American" being much more damning in that context than "woman"...). Attitudes have probably moved on a little since then, but I'm not going to take sides!

The Bell Jar (1963) by Sylvia Plath (USA, 1932-1963) audiobook read by Maggie Gyllenhaal

An astonishing book in all sorts of ways, tipping preconceptions about gender, sexuality, mental health, and all sorts of other things into Boston Harbour with relentless determination. But also astonishing in the way it demonstrates just how much the world has moved on in the last sixty or seventy years (in no small part thanks to books like this). The description of the month Esther spends as a guest editor (=student intern) on a women's magazine reads like surreal social satire to us now, a description of a privileged world of show-kitchens, celebrity poets and haute couture millinery we can't even begin to take seriously, but of course it's directly based on Plath's experience at Mademoiselle in summer 1953.

With the perspective of half a century, a lot of the doors Plath was kicking against are standing wide open (but not all: growing up is still just as challenging as it always was, and there are still lots of difficult areas around mental health), and it's perhaps rather easier than it was in the early sixties to take exception to her narrator's very entitled, middle-class way of looking at the world. Although there were people who were aware of it even then: in her biographical note to this edition, Lois Ames quotes an evaluation of Plath's application for a grant from a literary foundation, where the assessor points out that Plath is exactly the sort of person who always wins scholarships and bursaries and it wouldn't do any harm to give one to somebody else for a change.

What doesn't change, and what will always make this a book you should read, is the radical way Plath's language cuts through to the absurdity of the world around her. Every image she deploys is even more precise and unexpected than the one before it, and you keep having to stop and ask yourself whether you really heard it right.

Anyway, I haven't read it since I was about seventeen, when I had to read it more or less clandestinely, not so much because anyone was afraid that I might get the wrong sort of ideas, but rather because it would have provoked comments from parents and teachers about "that terrible American woman who ruined Ted Hughes's life" ("American" being much more damning in that context than "woman"...). Attitudes have probably moved on a little since then, but I'm not going to take sides!

The Bell Jar (1963) by Sylvia Plath (USA, 1932-1963) audiobook read by Maggie Gyllenhaal

An astonishing book in all sorts of ways, tipping preconceptions about gender, sexuality, mental health, and all sorts of other things into Boston Harbour with relentless determination. But also astonishing in the way it demonstrates just how much the world has moved on in the last sixty or seventy years (in no small part thanks to books like this). The description of the month Esther spends as a guest editor (=student intern) on a women's magazine reads like surreal social satire to us now, a description of a privileged world of show-kitchens, celebrity poets and haute couture millinery we can't even begin to take seriously, but of course it's directly based on Plath's experience at Mademoiselle in summer 1953.

With the perspective of half a century, a lot of the doors Plath was kicking against are standing wide open (but not all: growing up is still just as challenging as it always was, and there are still lots of difficult areas around mental health), and it's perhaps rather easier than it was in the early sixties to take exception to her narrator's very entitled, middle-class way of looking at the world. Although there were people who were aware of it even then: in her biographical note to this edition, Lois Ames quotes an evaluation of Plath's application for a grant from a literary foundation, where the assessor points out that Plath is exactly the sort of person who always wins scholarships and bursaries and it wouldn't do any harm to give one to somebody else for a change.

What doesn't change, and what will always make this a book you should read, is the radical way Plath's language cuts through to the absurdity of the world around her. Every image she deploys is even more precise and unexpected than the one before it, and you keep having to stop and ask yourself whether you really heard it right.

9thorold

Another from my pile of borrowed South African books.

Elsa Joubert was a distinguished Afrikaans travel-writer and novelist; this book was her big international success. Sad to see that she died three weeks ago, one of the victims of COVID-19.

The long journey of Poppie Nongena (Afrikaans 1978; English 1980) by Elsa Joubert (South Africa, 1922-2020) (author's own translation)

Poppie is the life-story of an ordinary black South African woman, who gets caught up in the injustices of the Pass Law system that was one of the cornerstones of apartheid. Her life becomes a constant struggle to stay on the right side of the bureaucracy whilst still finding time to care for her children and earn a living.

Although it's set out as a novel, Joubert makes it clear that she is telling us the story of a real person, as told to her by the woman and members of her family, with nothing changed except the names. (She shared the royalties from the book and the later stage-play with the original of "Poppie", who was able to buy a house for herself as a result.)

It's written in the simplest of language (I sampled the Afrikaans text as well as the English version: in Afrikaans it feels positively brutal in its directness), but it turns into a sophisticated exploration of what it feels like to make your life in a world you have absolutely no control over, and on the intersection between different cultures. Poppie and her family are constantly in tension between Xhosa and Afrikaans language, Christian and Xhosa culture, urban and rural ways of life, and so on, as well as having to cope with the illogical requirements of a law that deems you to be a resident of a place you have no tangible connection with, and an undesirable intruder in the region where you and your family have always lived. And takes it for granted that people living on low wages are somehow able to give up big chunks of their working time to queue up every time they need to have any contact with officialdom.

In the background of the story is South African history from World War II to the township violence of the seventies: Poppie doesn't see herself as political, she's too busy surviving and trying to make opportunities for the next generation, but when her younger siblings and her children get involved in protest, she understands perfectly well why they are angry. But she also has a pretty good idea that it's not going to end well for them.

Obviously, this is an educated, middle-class, white writer, transcribing the words of someone from a completely different background, so there's got to be an element of fraud in this, even if only at the subconscious level, but it's very convincingly done, and Joubert manages to give us the illusion that we are really seeing the world from Poppie's point of view. This seems to have been a book that opened a lot of people's eyes to the realities of apartheid, inside and outside South Africa.

Elsa Joubert was a distinguished Afrikaans travel-writer and novelist; this book was her big international success. Sad to see that she died three weeks ago, one of the victims of COVID-19.

The long journey of Poppie Nongena (Afrikaans 1978; English 1980) by Elsa Joubert (South Africa, 1922-2020) (author's own translation)

Poppie is the life-story of an ordinary black South African woman, who gets caught up in the injustices of the Pass Law system that was one of the cornerstones of apartheid. Her life becomes a constant struggle to stay on the right side of the bureaucracy whilst still finding time to care for her children and earn a living.

Although it's set out as a novel, Joubert makes it clear that she is telling us the story of a real person, as told to her by the woman and members of her family, with nothing changed except the names. (She shared the royalties from the book and the later stage-play with the original of "Poppie", who was able to buy a house for herself as a result.)

It's written in the simplest of language (I sampled the Afrikaans text as well as the English version: in Afrikaans it feels positively brutal in its directness), but it turns into a sophisticated exploration of what it feels like to make your life in a world you have absolutely no control over, and on the intersection between different cultures. Poppie and her family are constantly in tension between Xhosa and Afrikaans language, Christian and Xhosa culture, urban and rural ways of life, and so on, as well as having to cope with the illogical requirements of a law that deems you to be a resident of a place you have no tangible connection with, and an undesirable intruder in the region where you and your family have always lived. And takes it for granted that people living on low wages are somehow able to give up big chunks of their working time to queue up every time they need to have any contact with officialdom.

In the background of the story is South African history from World War II to the township violence of the seventies: Poppie doesn't see herself as political, she's too busy surviving and trying to make opportunities for the next generation, but when her younger siblings and her children get involved in protest, she understands perfectly well why they are angry. But she also has a pretty good idea that it's not going to end well for them.

Obviously, this is an educated, middle-class, white writer, transcribing the words of someone from a completely different background, so there's got to be an element of fraud in this, even if only at the subconscious level, but it's very convincingly done, and Joubert manages to give us the illusion that we are really seeing the world from Poppie's point of view. This seems to have been a book that opened a lot of people's eyes to the realities of apartheid, inside and outside South Africa.

10baswood

I must get to The Bell Jar

11AlisonY

Great reviews as always, and wow - what an impressive amount of books so far this year. I seemed to buck the trend with less time to read in Lockdown than normal.

Ah, The Bell Jar. I also need to give that a re-read sometime. I have the memory of a goldfish when it comes to books (even those I really enjoyed), and I must confess to remembering very little about it now.

Ah, The Bell Jar. I also need to give that a re-read sometime. I have the memory of a goldfish when it comes to books (even those I really enjoyed), and I must confess to remembering very little about it now.

12janemarieprice

>8 thorold: I haven't gotten to this yet but your review intrigues me because I feel like I've seen lots about it but never much mention of the plot so thank you for that!

13thorold

>10 baswood: - >12 janemarieprice: I'm glad I re-read it, but it is a slightly odd feeling coming (back) to a book like that relatively late in life — feels almost like trespassing, somehow.

Back to the TBR shelf. This is a Dutch novel I bought in 2012, after reading a couple of other novels by Hermans. He counts as one of the alpha-males of postwar Dutch literature(*), with Harry Mulisch and Gerard Reve (not that the three of them had much in common!). Hermans taught geography at Groningen University, hence his most famous novel, the geography-field-trip-from-hell Nooit meer slapen (Beyond Sleep). That and his war novel The darkroom of Damocles are fairly easy to find in English; this one doesn't seem to have been translated:

Uit talloos veel miljoenen (1981) by Willem Frederik Hermans (Netherlands, 1921-1995)

Hermans is known for bleak, philosophical novels, so it's a little unexpected to find yourself here in what looks like a satirical campus farce, in a late-seventies register somewhere between The history man and Abigail's party. But with a hint of Stoner too! Clemens is a sociology lecturer in Groningen, middle-aged and despairing of ever making it to full professor, rapidly losing his faith in the professional advantages of sticking to Marx and Marcuse. His wife, Sita, knows that the other faculty-wives look down on her: they are all students who married their professors; she was serving in a snack-bar when she met Clemens. She has hopes of publishing a successful children's book, like her neighbour Alies, but things seem to keep going wrong with the project, roughly in proportion to the rate at which the level of sherry goes down in the "vinegar" bottle in the kitchen. Meanwhile, her beautiful daughter, Parel, also seems to be heading full-tilt down some kind of slippery slope.

There's a lot of play with academic one-upmanship, and with the L-shaped living-rooms and sofas of suburban life (and the green letterboxes that keep getting pinched from suburban front gardens), and there are plenty of the kind of painfully embarrassing coincidences that belong to that kind of farce. But it gradually becomes obvious that there's also something darker going on. Sita's little book, "Beertje Bombazijn" (which Hermans wrote and actually published, under Sita's name) has its surreal side: one of the bears plays the tambourine and keeps a gypsy on a chain to collect the money for him. And actual bears, dream-bears and teddy-bears keep popping up in the novel in bizarre ways. There are suggestions of medieval allegory in many of the character names, and a strong hint — in a gratuitous walk-on appearance by the Professor of Middle English — that we should be looking for parallels with the poem "The Pearl".

Funny, in a warped way, and with some very acute bits of social observation. But maybe a bit more heavily-layered with meaning than it absolutely needs to be.

---

After having it around for a few days, I'm finding that very aggressive negative kerning on the cover more and more disquieting. I suppose it's meant to give a tombstone effect...

(*) Interesting in the context of the recent South Africa theme: a couple of years after this book came out Hermans caused a scandal by giving a series of lectures in South Africa, in violation of the cultural boycott. Of course he wasn't in any way a supporter of apartheid (he was married to a non-white woman), but his act of provocation led to him being declared "persona non grata" by the Amsterdam city council.

Back to the TBR shelf. This is a Dutch novel I bought in 2012, after reading a couple of other novels by Hermans. He counts as one of the alpha-males of postwar Dutch literature(*), with Harry Mulisch and Gerard Reve (not that the three of them had much in common!). Hermans taught geography at Groningen University, hence his most famous novel, the geography-field-trip-from-hell Nooit meer slapen (Beyond Sleep). That and his war novel The darkroom of Damocles are fairly easy to find in English; this one doesn't seem to have been translated:

Uit talloos veel miljoenen (1981) by Willem Frederik Hermans (Netherlands, 1921-1995)

Hermans is known for bleak, philosophical novels, so it's a little unexpected to find yourself here in what looks like a satirical campus farce, in a late-seventies register somewhere between The history man and Abigail's party. But with a hint of Stoner too! Clemens is a sociology lecturer in Groningen, middle-aged and despairing of ever making it to full professor, rapidly losing his faith in the professional advantages of sticking to Marx and Marcuse. His wife, Sita, knows that the other faculty-wives look down on her: they are all students who married their professors; she was serving in a snack-bar when she met Clemens. She has hopes of publishing a successful children's book, like her neighbour Alies, but things seem to keep going wrong with the project, roughly in proportion to the rate at which the level of sherry goes down in the "vinegar" bottle in the kitchen. Meanwhile, her beautiful daughter, Parel, also seems to be heading full-tilt down some kind of slippery slope.

There's a lot of play with academic one-upmanship, and with the L-shaped living-rooms and sofas of suburban life (and the green letterboxes that keep getting pinched from suburban front gardens), and there are plenty of the kind of painfully embarrassing coincidences that belong to that kind of farce. But it gradually becomes obvious that there's also something darker going on. Sita's little book, "Beertje Bombazijn" (which Hermans wrote and actually published, under Sita's name) has its surreal side: one of the bears plays the tambourine and keeps a gypsy on a chain to collect the money for him. And actual bears, dream-bears and teddy-bears keep popping up in the novel in bizarre ways. There are suggestions of medieval allegory in many of the character names, and a strong hint — in a gratuitous walk-on appearance by the Professor of Middle English — that we should be looking for parallels with the poem "The Pearl".

Funny, in a warped way, and with some very acute bits of social observation. But maybe a bit more heavily-layered with meaning than it absolutely needs to be.

---

After having it around for a few days, I'm finding that very aggressive negative kerning on the cover more and more disquieting. I suppose it's meant to give a tombstone effect...

(*) Interesting in the context of the recent South Africa theme: a couple of years after this book came out Hermans caused a scandal by giving a series of lectures in South Africa, in violation of the cultural boycott. Of course he wasn't in any way a supporter of apartheid (he was married to a non-white woman), but his act of provocation led to him being declared "persona non grata" by the Amsterdam city council.

14thorold

Another borrowed South African book from the pile brought back from the book picnic a couple of weeks ago...

Propaganda by monuments & other stories (1996) by Ivan Vladislavić (South Africa, 1957- )

This is the second short story collection by Vladislavić, from 1996. The eleven stories vary from the relatively conventional to the insanely busy: there's a lot of very good stuff, but in places a good idea seems to be buried under the weight of a thousand others, as in the title story — where a shebeen-owner writes off to the Soviet foreign ministry to enquire about the possibility of acquiring a surplus statue of Lenin to decorate his newly-legal tavern — or "Autopsy", where The King is spotted coming out of Estoril Books in Johannesburg. The surreal "Isle of Capri" and the Borgesian "The Omniscope" are less extreme examples, but still seem to be trying a bit too hard.

I particularly enjoyed "The Tuba", where an old-school racist tries to disrupt a Salvation Army band and ends up making music with them, and "The Book Lover", where the narrator explores inconclusive clues to the life of an earlier owner, a woman called Helena Shein, he finds in secondhand books from in various Johannesburg bookshops (this was especially fun because several of the books concerned are ones I happened to read recently). "The Whites Only bench" is another very good story, as is "Courage", a story about an artist who comes to a remote village to look for a model for a post-liberation statue. "'Kidnapped'" (a story about not writing a story) and "The Firedogs" were fun too.

Not in the same league as his more recent book Portrait with keys, but a very interesting collection.

Propaganda by monuments & other stories (1996) by Ivan Vladislavić (South Africa, 1957- )

This is the second short story collection by Vladislavić, from 1996. The eleven stories vary from the relatively conventional to the insanely busy: there's a lot of very good stuff, but in places a good idea seems to be buried under the weight of a thousand others, as in the title story — where a shebeen-owner writes off to the Soviet foreign ministry to enquire about the possibility of acquiring a surplus statue of Lenin to decorate his newly-legal tavern — or "Autopsy", where The King is spotted coming out of Estoril Books in Johannesburg. The surreal "Isle of Capri" and the Borgesian "The Omniscope" are less extreme examples, but still seem to be trying a bit too hard.

I particularly enjoyed "The Tuba", where an old-school racist tries to disrupt a Salvation Army band and ends up making music with them, and "The Book Lover", where the narrator explores inconclusive clues to the life of an earlier owner, a woman called Helena Shein, he finds in secondhand books from in various Johannesburg bookshops (this was especially fun because several of the books concerned are ones I happened to read recently). "The Whites Only bench" is another very good story, as is "Courage", a story about an artist who comes to a remote village to look for a model for a post-liberation statue. "'Kidnapped'" (a story about not writing a story) and "The Firedogs" were fun too.

Not in the same league as his more recent book Portrait with keys, but a very interesting collection.

15thorold

Zolathon — The Bonus Episodes (1/??)

I'm part way through several other books, but the DHL man turned up with a packet of essential supplies from Hay-on-Wye just as I was about to sit down to lunch. This little book didn't really seem long enough to bother putting it on the TBR shelf:

Emile Zola : an introductory study of his novels (1952) by Angus Wilson (UK, 1913-1991)

In just under 150 pages, Wilson manages to fit in a summary of Zola's life, a detailed appreciation of his strengths and weaknesses as a novelist, and a bluffer's guide to the entire Rougon-Macquart sequence, as well as a humorous appendix on English translations of Zola. He has the great advantage that he's writing (in 1952) at a point when Zola's reputation was at pretty much its lowest ebb in the English-speaking literary world, and not much higher in France, so there's a great feeling of freshness and discovery in his argument that Zola should be seen, like Dickens, Balzac and Dostoevsky, as a writer who offers "a wonderful, enveloping world". He is someone we should all be going out to read — provided we can read French, of course, since there were at that time no usable English versions available. The only translations he admits are the privately-printed Lutetian Society ones by Havelock Ellis, Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symonds, but they were essentially unobtainable to ordinary mortals.

Wilson's overall views on the series perhaps aren't all that radical, from a 21st century viewpoint: L'Assommoir, Germinal and La Terre are picked out as the high-points, with La Débâcle close behind. He finds flaws in Nana and La bête humaine, but interestingly also picks out La joie de vivre as a book that came very close to being great. He points out how autobiographical it is, and feels that it was "broken by the overflow of the author's personal passions," being written in the aftermath of his mother's death.

Wilson sensibly urges readers to ignore Zola's theories of literature and the dodgy scientific theories that provide some of the scaffolding for the family saga. He puts these down to Zola's rather patchy education and his perceived need to compensate for it, something we can't really blame him for. As far as Wilson is concerned, Zola at his best ignores the theory anyway, and lets the needs of the book he's writing drive what he does. When he lets the theory take over, or writes a book he's no longer interested in in the way his plan laid out, then things go wrong: in La bête humaine the crime plot that was meant for another book had to be shoehorned into a railway novel where it didn't really belong; by the time he got to L'Argent he'd found happiness in his personal life and gone from savagery to sterility in his writing.

Maybe it's occasionally a bit facile, and Wilson does enjoy making space for a memorably pithy comment, but it's stood up very well: this doesn't really feel like a book that's closer in time to Zola than it is to us!

---

Just compare the pleasant typography on this fifties Secker & Warburg dust-jacket with >13 thorold:; you'll see what I meant about the kerning!

I'm part way through several other books, but the DHL man turned up with a packet of essential supplies from Hay-on-Wye just as I was about to sit down to lunch. This little book didn't really seem long enough to bother putting it on the TBR shelf:

Emile Zola : an introductory study of his novels (1952) by Angus Wilson (UK, 1913-1991)

In just under 150 pages, Wilson manages to fit in a summary of Zola's life, a detailed appreciation of his strengths and weaknesses as a novelist, and a bluffer's guide to the entire Rougon-Macquart sequence, as well as a humorous appendix on English translations of Zola. He has the great advantage that he's writing (in 1952) at a point when Zola's reputation was at pretty much its lowest ebb in the English-speaking literary world, and not much higher in France, so there's a great feeling of freshness and discovery in his argument that Zola should be seen, like Dickens, Balzac and Dostoevsky, as a writer who offers "a wonderful, enveloping world". He is someone we should all be going out to read — provided we can read French, of course, since there were at that time no usable English versions available. The only translations he admits are the privately-printed Lutetian Society ones by Havelock Ellis, Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symonds, but they were essentially unobtainable to ordinary mortals.

Wilson's overall views on the series perhaps aren't all that radical, from a 21st century viewpoint: L'Assommoir, Germinal and La Terre are picked out as the high-points, with La Débâcle close behind. He finds flaws in Nana and La bête humaine, but interestingly also picks out La joie de vivre as a book that came very close to being great. He points out how autobiographical it is, and feels that it was "broken by the overflow of the author's personal passions," being written in the aftermath of his mother's death.

Wilson sensibly urges readers to ignore Zola's theories of literature and the dodgy scientific theories that provide some of the scaffolding for the family saga. He puts these down to Zola's rather patchy education and his perceived need to compensate for it, something we can't really blame him for. As far as Wilson is concerned, Zola at his best ignores the theory anyway, and lets the needs of the book he's writing drive what he does. When he lets the theory take over, or writes a book he's no longer interested in in the way his plan laid out, then things go wrong: in La bête humaine the crime plot that was meant for another book had to be shoehorned into a railway novel where it didn't really belong; by the time he got to L'Argent he'd found happiness in his personal life and gone from savagery to sterility in his writing.

Maybe it's occasionally a bit facile, and Wilson does enjoy making space for a memorably pithy comment, but it's stood up very well: this doesn't really feel like a book that's closer in time to Zola than it is to us!

---

Just compare the pleasant typography on this fifties Secker & Warburg dust-jacket with >13 thorold:; you'll see what I meant about the kerning!

16thorold

BTW: for anyone who’s following my opera adventures, I noticed that the fantastic Nederlandse Reisoper production of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo I saw live (it seems like a hundred years ago...) in February is now available through OperaVision: https://youtu.be/1R_ROOxxX9A

Highly recommended! A really superb collaboration between director, choreographer and the set, costume and lighting designers. (And an all-female production team.)

Highly recommended! A really superb collaboration between director, choreographer and the set, costume and lighting designers. (And an all-female production team.)

17thorold

>16 thorold: ...and last night I saw the 2017 Covent Garden La Bohème — always a fun opera to watch, and Michael Fabiano as Rodolfo was making all the right noises, but Australian soprano Nicole Car somehow managed to turn Mimì into something more like Joyce Grenfell as the school hockey captain. Least plausible death from consumption ever, but I think that could have been deliberate: we were supposed to wonder whether her illness wasn't wished upon her as the product of Rodolfo's warped romantic ideas.

---

Back to the TBR pile and East German classics of the sixties:

Die Aula (1965) by Hermann Kant (DDR, Germany, 1926-2016)

Hermann Kant, president of the writers' union, member of parliament and of the Central Committee, defender of censorship and tireless fighter against the evils of the capitalist West, was the public face of repressive authority in just about all the unedifying conflicts of the East German government with his fellow-writers. Volker Weidermann describes him as "the most-unloved, most-hated writer of the Wende period". It's almost disappointing to discover that he was actually quite a good writer in his early days...

Die Aula was one of the bestselling East German books of its time, becoming a firm fixture on school reading-lists, and also doing very well internationally (although I can't find any trace of an English translation). The central character, Robert, has a very similar background to Kant: he trained as an electrician, was called up for military service shortly before the end of the war, became a PoW in Poland, and followed antifascist training there (one of Kant's mentors in Warsaw was Anna Seghers, whom he later succeeded as president of the writers' union). Returning to Germany on his release in 1949, Robert gets a place in one of the new "Workers' and Peasants' Faculties" (ABFs) at a university in Pomerania, an intensive pre-university course for people who didn't get the chance to finish high-school. The novel centres on Robert's memories of his experiences at the ABF and the group of friends he made there, as recalled thirteen years later when — now a well-known journalist — he is invited to give a speech (in the great hall of the university, the Aula) to mark the ABF's last graduation ceremony before it is wound down.

So it's essentially an edifying story of keen young carpenters, seamstresses and agricultural workers who work hard to become doctors, senior civil servants, professors of Sinology, and so on, absolutely soaked in the atmosphere of the early days of the Workers' and Peasants' State, and of course permitting no doubt — in the mind of any reader Kant could imagine — that socialism is good, capitalism is bad, and the Federal Republic is worst of all. Propaganda, inevitably, but it's told with wit, irony, self-mockery, and huge amounts of energy. The characters are complicated, funny, and original, the dialogue is sharp and down-to-earth. Self-importance is never allowed to go unpunished, whether it comes from the pompous old academics who suddenly find themselves teaching students from a completely different section of society, party officials, or the students themselves. And, as we gradually discover, there is also a real personal conflict going on inside Robert: he has unfinished business with at least two of his student friends, which he is hoping to resolve through his journey into the past.

It's a very enjoyable, readable book, full of memorable anecdotes and period atmosphere and never overtly preachy, but it's a bit of a shaggy mess, and it sometimes feels as though the author has got into it but isn't quite sure how he's ever going to get out again. The ending, when it does come, feels a bit heavy-handed compared to the rest of the book. A flawed book in many ways, but one that deserves to go on being read.

---

Another text-heavy dustjacket, and this one, for unaccountable reasons, has got the book's epigraph on it (it's a quotation from Heine, referring to the French July Revolution of 1830)

---

Back to the TBR pile and East German classics of the sixties:

Die Aula (1965) by Hermann Kant (DDR, Germany, 1926-2016)

Hermann Kant, president of the writers' union, member of parliament and of the Central Committee, defender of censorship and tireless fighter against the evils of the capitalist West, was the public face of repressive authority in just about all the unedifying conflicts of the East German government with his fellow-writers. Volker Weidermann describes him as "the most-unloved, most-hated writer of the Wende period". It's almost disappointing to discover that he was actually quite a good writer in his early days...

Die Aula was one of the bestselling East German books of its time, becoming a firm fixture on school reading-lists, and also doing very well internationally (although I can't find any trace of an English translation). The central character, Robert, has a very similar background to Kant: he trained as an electrician, was called up for military service shortly before the end of the war, became a PoW in Poland, and followed antifascist training there (one of Kant's mentors in Warsaw was Anna Seghers, whom he later succeeded as president of the writers' union). Returning to Germany on his release in 1949, Robert gets a place in one of the new "Workers' and Peasants' Faculties" (ABFs) at a university in Pomerania, an intensive pre-university course for people who didn't get the chance to finish high-school. The novel centres on Robert's memories of his experiences at the ABF and the group of friends he made there, as recalled thirteen years later when — now a well-known journalist — he is invited to give a speech (in the great hall of the university, the Aula) to mark the ABF's last graduation ceremony before it is wound down.

So it's essentially an edifying story of keen young carpenters, seamstresses and agricultural workers who work hard to become doctors, senior civil servants, professors of Sinology, and so on, absolutely soaked in the atmosphere of the early days of the Workers' and Peasants' State, and of course permitting no doubt — in the mind of any reader Kant could imagine — that socialism is good, capitalism is bad, and the Federal Republic is worst of all. Propaganda, inevitably, but it's told with wit, irony, self-mockery, and huge amounts of energy. The characters are complicated, funny, and original, the dialogue is sharp and down-to-earth. Self-importance is never allowed to go unpunished, whether it comes from the pompous old academics who suddenly find themselves teaching students from a completely different section of society, party officials, or the students themselves. And, as we gradually discover, there is also a real personal conflict going on inside Robert: he has unfinished business with at least two of his student friends, which he is hoping to resolve through his journey into the past.

It's a very enjoyable, readable book, full of memorable anecdotes and period atmosphere and never overtly preachy, but it's a bit of a shaggy mess, and it sometimes feels as though the author has got into it but isn't quite sure how he's ever going to get out again. The ending, when it does come, feels a bit heavy-handed compared to the rest of the book. A flawed book in many ways, but one that deserves to go on being read.

---

Another text-heavy dustjacket, and this one, for unaccountable reasons, has got the book's epigraph on it (it's a quotation from Heine, referring to the French July Revolution of 1830)

18thorold

This is a book I've been mildly curious about since it came out, but never quite enough to go out and look for it. Finally, a copy strayed into my path — fun to see that it was a review copy, still with a press release, a "with compliments" slip, and a carbon copy of the review (yes, we still had carbon paper in 1988!) folded into the back cover. The reviewer's verdict seems to have been "modified rapture".

The parrot and other poems (1988) by P G Wodehouse (UK, 1881-1975)

P G Wodehouse might have made fun of poets in his stories, but he didn't in the least despise verse: anyone who's ever read one of his books will know how much he enjoyed quoting the English classics in inappropriate contexts, and anyone who knows anything about his writing career will be aware that he was a highly successful Broadway lyricist around the time of the Great War. He always had a very sharp ear for rhyme and metre.

This collection of comic verse is mostly taken from Wodehouse's very early newspaper days, between around 1903 and 1907, together with a couple of poems that appeared in later stories (like the immortal nature poem "Good Gnus", which is written by Charlotte Mulliner in "Unpleasantness at Budleigh Court"). The newspaper poems deal with issues of the day: ladies' cricket, the craze for bridge, the post-Reichenbach revival of Sherlock Holmes, H.G. Wells's comet, and so on. Prominent are the "Parrot" poems, part of a daily sequence printed in the Express in Autumn 1903 as an ironic commentary on the Free Trade debate of the moment, and owing more than a little to a certain American bird famous for perching above doors.

As you would expect, this is hack work, written at speed to fill empty columns, with the expectation that it would be wrapping fish the next day, and it doesn't really survive being printed in a book a century later. Everything is a parody of one kind or another, with the footprints of Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, and — above all — W S Gilbert visible on every page, but here and there you can see the glimmerings of original Wodehouse humour beginning to shine through.

The introductions by Auberon Waugh and Frances Donaldson are pleasant, but don't say very much (and what they do say overlaps rather!); the cartoons by David Langdon are fun, although he's rather anachronistically chosen to caricature Wodehouse as he was in his seventies, not as the sporting young man of twenty who wrote most of these poems.

Not a must-have book, but still quite a nice addition to a Wodehouse collection.

---

The magic of alphabetical order: this gets slotted in between William Carlos Williams and Gerard Woodward on my poetry shelf! Wheelbarrows to one side, punk and Domestos to the other...

The parrot and other poems (1988) by P G Wodehouse (UK, 1881-1975)

P G Wodehouse might have made fun of poets in his stories, but he didn't in the least despise verse: anyone who's ever read one of his books will know how much he enjoyed quoting the English classics in inappropriate contexts, and anyone who knows anything about his writing career will be aware that he was a highly successful Broadway lyricist around the time of the Great War. He always had a very sharp ear for rhyme and metre.

This collection of comic verse is mostly taken from Wodehouse's very early newspaper days, between around 1903 and 1907, together with a couple of poems that appeared in later stories (like the immortal nature poem "Good Gnus", which is written by Charlotte Mulliner in "Unpleasantness at Budleigh Court"). The newspaper poems deal with issues of the day: ladies' cricket, the craze for bridge, the post-Reichenbach revival of Sherlock Holmes, H.G. Wells's comet, and so on. Prominent are the "Parrot" poems, part of a daily sequence printed in the Express in Autumn 1903 as an ironic commentary on the Free Trade debate of the moment, and owing more than a little to a certain American bird famous for perching above doors.

As you would expect, this is hack work, written at speed to fill empty columns, with the expectation that it would be wrapping fish the next day, and it doesn't really survive being printed in a book a century later. Everything is a parody of one kind or another, with the footprints of Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, and — above all — W S Gilbert visible on every page, but here and there you can see the glimmerings of original Wodehouse humour beginning to shine through.

The introductions by Auberon Waugh and Frances Donaldson are pleasant, but don't say very much (and what they do say overlaps rather!); the cartoons by David Langdon are fun, although he's rather anachronistically chosen to caricature Wodehouse as he was in his seventies, not as the sporting young man of twenty who wrote most of these poems.

Not a must-have book, but still quite a nice addition to a Wodehouse collection.

---

The magic of alphabetical order: this gets slotted in between William Carlos Williams and Gerard Woodward on my poetry shelf! Wheelbarrows to one side, punk and Domestos to the other...

19thorold

And another literary biography — both Jonathan Coe and B S Johnson are writers I've come across only fairly recently, with nothing obvious in common, and it's fun finding out that one is a big fan of the other. Like one of those dinner-parties where you bring together friends from different contexts and discover that they've actually known each other for years...

Like a fiery elephant : the story of B.S. Johnson (2004) by Jonathan Coe (UK, 1961- )

B S Johnson got a relatively late start as a writer, having come up the hard way through the education system, and he died very young, only ten years after his first book was published. Moreover, he was doctrinally opposed to the idea of fiction, all his novels and poems and most of his writing for film or stage being drawn in one way or another from his own life. So there couldn't be very much left for a biographer to do, surely?

Not so. Coe tells us he spent more than eight years, on and off, researching and writing this book, and he obviously had a hard time making his mind up about what conclusions — if any — could be drawn about Johnson's life. As a result, we get a book that, while it doesn't come in a box or have holes in the pages, is quite unusual in form by the standards of literary biography. Coe first takes us through Johnson's main works, the seven novels, and only then tackles the "life" part, following a roughly chronological sequence guided by 160 "fragments" from Johnson's writings (books, letters, rough notes, essays, application forms, etc.). He tries to make some kind of sense of how this combative, self-assured writer who always seemed to be quite certain that the peculiar theoretical path he was beating through the literary jungle was the only possible valid one, could end up messing up so many of the projects he worked on and antagonising so many of the people who could have been helping him.

Not straightforward, and Coe doesn't try to pretend that there are any sweeping generalisations to be made, but we do end up with some ideas that help us to understand Johnson a little bit better. Although it's not really clear by the end of the book whether Coe has really managed to convince himself that literary biography is a valid thing to do. He pats himself on the back a couple of times when he finds texts that Johnson has filed away noting that "this will go in me memoirs one day," but he has to step back and leave us with a bit of literary ambiguity when he comes to questions that only Johnson himself could have resolved for us, especially the big one of why he chose to end his life in November 1973.

A very interesting biography, and a book that raises quite a few questions about the way we evaluate literary success and standing, the ways writers are rewarded, and so on, that are obviously still worth thinking about now. A minor disappointment is that we don't get to learn much about Johnson's relationship with the person he regarded as his most important mentor, Samuel Beckett, presumably because Coe couldn't get permission to use their letters. But there is a lot about Johnson's other literary friendships, and a very entertaining selection of his angry letters — one of the best is addressed to a distinguished US publisher and opens with "You ignorant unliterary Americans make me puke." (Coe's Fragment 84, dated 28 June 1965).

Like a fiery elephant : the story of B.S. Johnson (2004) by Jonathan Coe (UK, 1961- )

B S Johnson got a relatively late start as a writer, having come up the hard way through the education system, and he died very young, only ten years after his first book was published. Moreover, he was doctrinally opposed to the idea of fiction, all his novels and poems and most of his writing for film or stage being drawn in one way or another from his own life. So there couldn't be very much left for a biographer to do, surely?

Not so. Coe tells us he spent more than eight years, on and off, researching and writing this book, and he obviously had a hard time making his mind up about what conclusions — if any — could be drawn about Johnson's life. As a result, we get a book that, while it doesn't come in a box or have holes in the pages, is quite unusual in form by the standards of literary biography. Coe first takes us through Johnson's main works, the seven novels, and only then tackles the "life" part, following a roughly chronological sequence guided by 160 "fragments" from Johnson's writings (books, letters, rough notes, essays, application forms, etc.). He tries to make some kind of sense of how this combative, self-assured writer who always seemed to be quite certain that the peculiar theoretical path he was beating through the literary jungle was the only possible valid one, could end up messing up so many of the projects he worked on and antagonising so many of the people who could have been helping him.

Not straightforward, and Coe doesn't try to pretend that there are any sweeping generalisations to be made, but we do end up with some ideas that help us to understand Johnson a little bit better. Although it's not really clear by the end of the book whether Coe has really managed to convince himself that literary biography is a valid thing to do. He pats himself on the back a couple of times when he finds texts that Johnson has filed away noting that "this will go in me memoirs one day," but he has to step back and leave us with a bit of literary ambiguity when he comes to questions that only Johnson himself could have resolved for us, especially the big one of why he chose to end his life in November 1973.