Labfs39 attempts to understand and remember

DiscussieHolocaust Literature

Sluit je aan bij LibraryThing om te posten.

1labfs39

I have been reading about the Holocaust for decades now and still feel the need to read more. I want to use this thread to track all of my reading on the Holocaust: fiction and nonfiction, memoirs, history, and graphic stories. I will add a review every few days until I have caught up with my previously reviewed titles. At the same time I will be adding new titles as I read them.

When did I first become interested in the Holocaust? I'm sure I read The Diary of a Young Girl as a young girl myself, but the other title that stands out in my memory is Playing for Time by Fania Fenelon. It is the memoir of a Paris cabaret singer who was deported to Auschwitz and survived by playing in the camp orchestra. It had a profound impact on me, and I think that was the beginning of my grim fascination.

I studied history and literature in college, focusing on the 19th century. The courses I took on Russia sparked a lifelong interest in Slavic studies. After graduating I began studying at the Russian and East European Institute, and this is when my interest in the Holocaust gained traction. I studied the literature and history of countries from the Baltics to the Balkans and began studying Czech. I met Art Speigelman and Maus opened my eyes to graphic memoirs of the Holocaust. I visited Terezin and Dachau. Cried on the salt-sown fields that are all that remains of Lidice.

Since then I have continued to read and, when the opportunities arise, visit Holocaust museums and sites like the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris. I look forward to learning more about the Holocaust by following your threads and discussions in this group.

When did I first become interested in the Holocaust? I'm sure I read The Diary of a Young Girl as a young girl myself, but the other title that stands out in my memory is Playing for Time by Fania Fenelon. It is the memoir of a Paris cabaret singer who was deported to Auschwitz and survived by playing in the camp orchestra. It had a profound impact on me, and I think that was the beginning of my grim fascination.

I studied history and literature in college, focusing on the 19th century. The courses I took on Russia sparked a lifelong interest in Slavic studies. After graduating I began studying at the Russian and East European Institute, and this is when my interest in the Holocaust gained traction. I studied the literature and history of countries from the Baltics to the Balkans and began studying Czech. I met Art Speigelman and Maus opened my eyes to graphic memoirs of the Holocaust. I visited Terezin and Dachau. Cried on the salt-sown fields that are all that remains of Lidice.

Since then I have continued to read and, when the opportunities arise, visit Holocaust museums and sites like the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris. I look forward to learning more about the Holocaust by following your threads and discussions in this group.

2labfs39

Books read in 2024:

1. Rome 16 October 1943 adaptation by Sarah Laing, original story by Giacomo Debenedetti (GN, 4.5*)

2. A Faraway Island and The Lily Pond by Annika Thor, translated from the Swedish by Linda Schenck (TYA, 4*)

3. Bitter Herbs: A Little Chronicle by Marga Minco, translated from the Dutch by Jeannette K. Ringold (TF, 4*)

Books read in 2023:

1. No Pretty Pictures: A Child of War by Anita Lobel (NF, 4*)

2. My Brother's Voice: How a Young Hungarian Boy Survived the Holocaust by Stephen Nasser with Sherry Rosenthal (NF, 4*)

Books read in 2022:

1. I Have Lived a Thousand Years: Growing Up in the Holocaust by Livia Bitton-Jackson (NF, 4.5*)

2. Maus: A Survivor's Tale by Art Spiegelman (GN, 4.5*)

3. Second Generation: Things I Didn't Tell My Father by Michel Kichka, translated from the French by Montana Kane (GN, 4.5*)

4. The Property by Rutu Modan, translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen (GN, 4*)

5. Romek's Lost Youth: The Story of a Boy Survivor by Ken Roman and John James (NF, 4.5*)

Books read in 2021

1. Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries by Laurel Holliday (NF, 4*)

2. Rena's Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz by Rena Kronreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam (NF, 4*)

3. Dora Bruder by Patrick Modiano, translated from the French by Joanna Kilmartin (TF, 3*)

4. The Note through the Wire by Doug Gold (NF, 3.5*)

5. Burned Child Seeks the Fire by Cordelia Edvardson, translated from the Swedish by Joel Agee (TNF, 4*)

6. A Delayed Life: The powerful memoir of the librarian of Auschwitz by Dita Kraus (NF, 4.5*)

1. Rome 16 October 1943 adaptation by Sarah Laing, original story by Giacomo Debenedetti (GN, 4.5*)

2. A Faraway Island and The Lily Pond by Annika Thor, translated from the Swedish by Linda Schenck (TYA, 4*)

3. Bitter Herbs: A Little Chronicle by Marga Minco, translated from the Dutch by Jeannette K. Ringold (TF, 4*)

Books read in 2023:

1. No Pretty Pictures: A Child of War by Anita Lobel (NF, 4*)

2. My Brother's Voice: How a Young Hungarian Boy Survived the Holocaust by Stephen Nasser with Sherry Rosenthal (NF, 4*)

Books read in 2022:

1. I Have Lived a Thousand Years: Growing Up in the Holocaust by Livia Bitton-Jackson (NF, 4.5*)

2. Maus: A Survivor's Tale by Art Spiegelman (GN, 4.5*)

3. Second Generation: Things I Didn't Tell My Father by Michel Kichka, translated from the French by Montana Kane (GN, 4.5*)

4. The Property by Rutu Modan, translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen (GN, 4*)

5. Romek's Lost Youth: The Story of a Boy Survivor by Ken Roman and John James (NF, 4.5*)

Books read in 2021

1. Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries by Laurel Holliday (NF, 4*)

2. Rena's Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz by Rena Kronreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam (NF, 4*)

3. Dora Bruder by Patrick Modiano, translated from the French by Joanna Kilmartin (TF, 3*)

4. The Note through the Wire by Doug Gold (NF, 3.5*)

5. Burned Child Seeks the Fire by Cordelia Edvardson, translated from the Swedish by Joel Agee (TNF, 4*)

6. A Delayed Life: The powerful memoir of the librarian of Auschwitz by Dita Kraus (NF, 4.5*)

3labfs39

A Delayed Life: The powerful memoir of the librarian of Auschwitz by Dita Kraus

Originally published in Czech 2018, English edition 2020; 474 p.

Read in 2021

I first learned about Dita Kraus when I read a review on LibraryThing of The Librarian of Auschwitz by Antonio Iturbe. It is a fictionalized account of her life during the Holocaust. The review led to an interesting conversation about ″based on the true story″ literature, the sensationalizing of the Holocaust, and the merits of fictional Holocaust literature. I decided to skip the novel and chose to read her memoir instead.

A Delayed Life is not only, or even primarily, a Holocaust story. The first quarter details her childhood in Prague, from her earliest memories through her thirteenth birthday. The second quarter covers the war years, 1942-45. The last half describes life in Prague after the war, her immigration to Israel, life on a kibbutz, her marriage, and teaching career. Taken in it′s entirety, it is a rich history of both a life and a time period.

Dita Polach was born in 1929, the only child of a middle class secular Jewish family. Her homey descriptions of her childhood in Prague—her relationship with her grandmother, being a picky eater, having her tonsils out, skating dresses, and trips to the countryside—were a delight to read. Little mention is made of political matters, because as a child, she was unaware of them. When she was thirteen, however, the war came crashing down around her, when she and her parents were deported to Terezín. She was thirteen years old.

One of the unique things about Dita is that she is one of the few survivors among the child artists at Terezín. Her drawings are on display in several exhibits around the world. Another is that although she was separated from her parents in Terezín, she was reunited with them in the BIIb or the Terezín

family camp at Auschwitz. Very few families were kept together at Auschwitz, but around 17,500 people from Terezín were transferred there. Unfortunately, only 1,294 survived. Dita and her mother were two of them. They were selected by Mengele for transport to Germany as slave labor and thus they avoided the crematorium. In the spring of 1945, as the front grew closer, the women were transported to Bergen-Belsen where they spent several harrowing and desperate months prior to liberation.

After the war, sixteen-year-old Dita returned to Prague and eventually decided to emigrate to Israel. This was another fascinating part of the book. She describes the process that the now communist Czech government required in order to emigrate: the documents needed, what you could and could not bring, how they traveled. All to end up inside a barbed-wire fence in Israel for months until they were found a place on a kibbutz. Her descriptions of life on the kibbutz were interesting, because although she wanted to succeed there, she was not a Zionist, and saw things without the passion of an idealist. Interestingly, one of her longest jobs there was as a cobbler.

The last part of the book deals with her teaching career, her husband, and children, bringing the reader to the present, 2018. Unfortunately in January of 2021, Dita contracted Covid at the age of 91 and was hospitalized for several weeks. She appears to have recovered. You can listen to an interview with her and see some of her artwork at her website: www.ditakraus.com.

I highly recommend this well-written and readable memoir.

4labfs39

Burned Child Seeks the Fire: A Memoir by Cordelia Edvardson, translated from the Swedish by Joel Agee

Published 1984, 106 p.

Read in 2021

Cordelia Edvardson was born in 1929 and raised in Berlin by her mother and grandmother. It was not an easy or happy childhood. Her relationship with her mother was difficult and from the age of twelve she did not live at home. Partially this was to protect her step-siblings from the perceived taint of her half-Jewish parentage. Although she was raised Catholic and her mother tried everything to keep her Jewish identity hidden (even having her be adopted by a Spanish couple so that Cordelia could have a Spanish passport), the Gestapo caught her. Cordelia was forced to either sign a paper saying she was Jewish and thus subject to the Nuremburg Laws or her mother would be prosecuted for hiding a Jew, which was treason.

In 1943 Cordelia was taken in a roundup and sent to Theresienstadt. She was fourteen-years-old. When she arrived, she was sent straight to prison for unknowingly having contraband and later released to the general camp. Less than a year later she was deported to Auschwitz where she was forced to labor in various factories. After liberation, she ended up in Sweden, where she became a citizen. Later she spent many years in Jerusalem as a Middle East correspondent for a Swedish newspaper.

Although quite short, this Holocaust memoir covers some themes and events that struck me as not typical. First, although Cordelia is young when most of the memoir takes place, this is not a coming of age story. It′s an adult′s clear-eyed perspective written in the concise language of a journalist. Second, there is no celebration of life after the war ends.

To put it behind her, to forget, to be healthy—the girl felt despair, rage, and hatred turning into a burning ball of fire in her throat. She still lacked words, but if she had had them, she would have screamed: ″But I don′t want it behind me, I don′t want to get healthy, I don′t want to forget! All you ever want to do is ′wipe the slate clean,′ as you all so complacently put it. You want to take my anguish from me, deny it and wipe it away and protect yourselves against my rage, but then you are wiping me our as well, ′eradicating′ me, as the Germans put it, then you deny me too, because I am all that...″

Cordelia struggles in her relationships and as a mother. Even Sweden galls her,

She, who still had a burnt smell in her hair and in her clothes, began to turn every stone and rummage through every heap of refuse, but all she found were some wood lice or the bones of birds. No skeletons marked by torture, no skulls showing evidence of gold teeth having been broken out of the jaw bones, no emaciated corpses of children.

In the midst of so much innocence she found it hard to breathe, and she realized she had to move on.

Cordelia ends up in Israel and, while reporting on the Yom Kippur War, finds acceptance and an odd sense of peace.

The threat of destruction and the people of the land looked each other in the eye with the familiarity of recognition. The survivors returned to the only form of life, the only task and challenge they had learned to master—the struggle for survival. But she felt, here human beings and the forces of destruction were meeting as combatants, the outcome was not predetermined, not this time. This was fair play.

I liked the tone of the memoir. Nothing is wrapped up with a pretty bow, the world is not let off the hook.

Her anger did not permit her to accept the pity and solicitude of others. They would have to try harder than that! She would not allow them to cry over her the way they had sobbed over Anne Frank′s diary…

With the touching letters to ″Kitty″ the world had received its catharsis at much too cheap a price—and pretty young actresses were being given a rewarding part to play on the stage and in the movies. The thought filled her with feelings of hatred.

Yet, Cordelia does find a place and a position that affords her self-respect and self-determination. She marries, has children. The memoir ends with a resounding, ″I am!″

5labfs39

Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries by Laurel Holliday

Published in 1995, 409 p.

Read in 2021

“Perhaps it is so painful to think about the impact of the war on children—particularly their mass executions—that we have not wanted to read about it, even when that has meant refusing to hear from the children themselves. Maybe it was as much as we could bear to designate Anne Frank the representative child of the Holocaust and to think, then, only of her when we thought about children in World War II.

But, in some ways, Anne Frank was not representative of children in the war and Holocaust. Because she was in hiding, she did not experience life in the streets, the ghettos, the concentration camps, as it was lived by millions of children throughout Europe.”

The Secret Diaries is an anthology of diaries written by children aged 10-18 from a smattering of countries across Europe. Both boys and girls, Jews and Gentiles are represented and their backgrounds include a variety of social classes and a rural/urban mix. Some of the children had been keeping a diary prior to the war, but most started one as a stress release or as a deliberate record of their experiences. The sheer variety makes the author’s point that no one child’s experience can represent the whole. The anthology includes entire diaries or extended excerpts and is organized by the child’s age, youngest to oldest. Each diary is preceded by several paragraphs describing what is known about the child and their fate.

The first diarist is ten-year-old Janine Phillips who started her diary in May 1939 when her extended family moved to the Polish countryside. She lived in relative comfort, and her diary is newsy and humorous, filling a 1000-page notebook in that one year. The family then moved back to Warsaw, and during the Ghetto Uprising she organized a first-aid station as a Girl Guide. She was arrested and taken to Germany as a prisoner of war. She was 16 when the war ended and she was released.

Ephraim Shtenkler was two-years-old when he was given to a Polish woman, who was paid to hide him. Unfortunately, she resented him and kept him locked in a cupboard, barely alive. He was rescued five years later and had to learn to walk. He wrote about his experiences when he was 11.

Another diary that haunts me is that of Eva Heyman. She was thirteen when the Nazis invaded and occupied Hungary. Her family had been active politically, so they knew they would be targets. Eva’s best friend, Marta, was shot by the Nazis, and Eva wrote often of her desire to live. Her diary ends abruptly on the day they were deported to Auschwitz.

“All I know is that I don’t believe anything anymore, all I think about it Marta, and I’m afraid that what happened to her is going to happen to us, too. It’s no use that everybody says that we’re not going to Poland but to Balaton. Even though, dear diary, I don’t want to die; I want to live even it if means that I’ll be the only person here allowed to stay. I would wait for the end of the war in some cellar, or on the roof, on in some secret cranny. I would even let the cross-eyed gendarme, the one who took our flour away from us, kiss me, just as long as they didn’t kill me, only that they should let me live.”

Ina Constantinova was sixteen when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. She was determined to fight for her country in a combat role. She joined the partisans as a saboteur and spy and died at the age of twenty covering the retreat of her comrades with a submachine gun. Hannah Senesh, too, was to die fighting. In 1939 she escaped Hungary and fled to Palestine, a devoted Zionist, at the age of seventeen. Over the course of the war, she became convinced that her role was to help organize the escape of other Jewish youth. She parachuted into Hungary in 1944, but was captured by the Nazis, tortured for months, then executed. She became a national hero, and her diary and poems are widely read throughout Israel.

Other children diarists wrote about the bombings, life in the ghettos, death marches. They wrote from hiding, from concentration camps, from prison. Their age spared them from nothing, yet their diaries were different from those of adult writers, yet it's difficult for me to say how. There is innocence, and yet many of them are exposed to horrors that belie the concept of innocence. Their concerns can be different—school, friends, crushes; or similar to adults—the search for food, a hiding spot, strength to live another day. Perhaps the difference lies in the sense of youth lost, whether acknowledged by the diarist (“29 July 1940 On the Last Day of My Childhood”) or by the reader alone.

6labfs39

Brodeck by Philippe Claudel, translated from the French by John Cullen

Originally published 2007, English translation 2009

Read 2011

Is collaboration in wartime an act of self-preservation or an opportunity to let out one’s secret distrust of The Other? Is collusion a collective, social act or a collection of single, personal decisions? How do you live with betrayal?

These are some of the questions explored in Philippe Claudel’s book, Brodeck’s Report. In a fairy tale village in the woods, a stranger has been murdered. Brodeck, a man recently returned from the camps, is asked to represent the village and write an official report of what occurred. At the same time, Brodeck writes a secret report, in his own voice, about what he learns and about his own life and the decisions he has made. The book begins:

I’m Brodeck and I had nothing to do with it.

I insist on that. I want everyone to know.

I had no part in it, and once I learned what had happened, I would have preferred never to mention it again, I would have liked to bind my memory fast and keep it that way, as subdued and still as a weasel in an iron trap.

But the others forced me.

From the first lines, before the reader even knows what has happened, she is asked to take sides. Is Brodeck innocent? Should some memories be allowed to fade away, or is there a moral imperative or human compulsion to share the truth?

I loved this book for the very ambiguity that makes the answers to these questions so difficult. In haunting imagery and beautiful language, Claudel leads Brodeck to the brink of the abyss and asks the reader to join him in looking in. A Holocaust novel without ever saying the words, Brodeck’s Report is easily one of the best books I’ve read this year, and I recommend it for its plot, its language, and most importantly for its ability to make me think.

7labfs39

A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy by Thomas Buergenthal, foreword by Elie Wiesel

Published 2009

Read in 2009

I have read many memoirs of Jews who survived the Holocaust, but this one stands out in my mind, although I can't quite put my finger on why. It may be his extreme youth and the extraordinary fact of his having survived Auschwitz at the age of ten, even after losing the protective presence of both parents. It may be the unusual fate of the boy after his release from the camps: becoming a mascot of the Polish army and the miracle of being reunited with a family member thought perished. Or maybe it is simply the tone of the book, measured, thoughtful, and reflective on the events that shaped his illustrious career as an international human rights judge. I think perhaps it may simply be the innocent joy and beauty present in the face of the little boy captured in photos with his parents that are included in the book. If this epitome of youthful exuberance and simple childish joy can be treated so callously and cruelly, with casual disdain, than how can we hope to avert less obvious evil?

They have forced me to reflect on what it is that allows or compels human beings to commit such cruel and brutal crimes. It frightens me terribly that the individuals committing these acts are for the most part not sadists, but ordinary people who go home in the evening to their families, washing their hands before sitting down to dinner, as if what they had been doing was just a job like any other. If we humans can so easily wash the blood of our fellow humans off our hands, then what hope is there for sparing future generations from a repeat of the genocides and mass killings of the past?

8labfs39

The Last of the Just by Andre Schwarz-Bart translated from the French by Stephen Becker

Originally published 1959, English translation 1960

Read in 2013

...the ancient Jewish tradition of the Lamed-Vov, a tradition that certain Talmudists trace back to the source of the centuries, to the mysterious time of the prophet Isaiah. Rivers of blood have flowed, columns of smoke have obscured the sky, but surviving all these dooms, the tradition has remained inviolate down to our own time. According to it, the world reposes upon thirty-six Just Men, the Lamed-Vov, indistinguishable from simple mortals; often they are unaware of their station. But if just one of them were lacking, the sufferings of mankind would poison even the souls of the newborn, and humanity would suffocate with a single cry. For the Lamed-Vov are the hearts of the world multiplied, and into them, as into one receptacle, pour all our griefs.

The Last of the Just is beautifully written and weaves history, legend, and religion into a fascinating story about the transference of the Just Man from one generation to the next within the Levy family, culminating in the life and death of Ernie Levy. The story begins with the horrific tales of Rabbi Yom Tov Levy and his progeny who suffered death and martyrdom over and over throughout the centuries in most of the countries of Europe. It is a seemingly endless cycle of persecution bringing us into the present with the story of Ernie's grandfather, Mordecai.

As an adolescent, Mordecai was forced to leave the shtetl of Zemyock, Poland and hire himself out as a farm hand in order to keep his parents and siblings from starvation. They would rather starve, because to the Hasidic Levy family, nothing is worth turning from the study of God. Furthermore, on every job, Mordecai is forced to fight in order to establish his place in the hierarchy. Eventually, he becomes an itinerant peddler and meets and falls in love with a fiery young woman named Judith. Although his family doesn't approve of her, eventually Mordecai and Judith settle in Zemyock and raise a family. Finally, Mordecai is able to devote himself to religious study.

Their oldest son, Benjamin, doesn't seem to fit the bill as the next Just Man. He is skinny and small with a large head, unlike his three more robust younger brothers, and Mordecai fairly ignores him. A vicious pogrom forces Benjamin to leave Zemyock and move to Germany, where things seem much safer than in Eastern Europe. Ah, do you see the shadow of destiny falling? Benjamin becomes a tailor and eventually earns enough to bring his parents to live with him and soon his wife. Completely cowed by the headstrong Judith, Fraulein Leah Blumenthal is the mother to a large brood of children, yet remains naive and impotent of power.

And so we come to Ernie, neither the oldest or youngest, small and unassuming, but possessed of an undeniably sensitive soul. Nurtured and protected by his family, especially the patriarch Mordecai, Ernie nonetheless suffers from the growing Nazi presence in Stillenstadt. The story of his childhood is sweet and horrible and a window into the suffering of Jewish children in 1930's Germany. Ernie's innocence is gnawed away until he is only a shell filled with despair and hopelessness. As a young man he wanders, believing himself to be nothing more than the dog the Nazi's have labeled him. The story of his redemption in Paris and his ultimate fate, I will leave you to discover, but needless to say, as a Just Man, Ernie's destiny is not an easy one.

I loved the language of this book, although it is not an easy read emotionally. The author writes beautifully of the tortures of a sensitive soul, affinity with nature, the trials of childhood relationships, and the bleakness of losing your way in life. And arching over all of this, humanity, lies the Holocaust. It's as awful as you might imagine, but even worse is the idea you are left with. What if we have murdered the Last Just Man? To what brink have we brought ourselves spiritually, and is it possible to recover?

Highly recommended.

9labfs39

The German Mujahid by Boualem Sansal, translated from the French by Frank Wynne

Originally published 2008, English translation 2009

Read in 2011

Billed as the first Arab novel to confront the Holocaust, The German Mujahid is a book that can be read in many different ways. Some reviewers have focused on Sansal's condemnation of the Algerian military, Islamic fundamentalists, and the corruption of life in modern Algeria. (The book has been banned there). Other reviewers on the oblique comparison of the ways in which the modern Islamic fundamentalists and the former Nazis wield power. What struck me most, however, was the question To what extent are we responsible for the crimes of our parents?

Rachel and Malrich Schiller brothers were born in Algeria to a German father and Algerian mother. In an effort to provide them with more opportunities, the parents send first one and then the other brother to France to live with their uncle. Growing up in one of the many tough Muslim ghettos in France, Rachel, the oldest, becomes the model immigrant, boldly striving for success in his new country. Seventeen-year-old Malrich, on the other hand, is struggling to create an identity for himself and is often in trouble with his uncle, his school, and the police. The book begins: Rachel died six months ago.

His brother's death leads Malrich on a voyage of discovery about his family, his brother, and himself. He begins reading Rachel's diary and learns that his brother's descent into madness and suicide began with the massacre of their parents in their backwater Algerian village by Islamic fundamentalists two years ago. Rachel was horrified by the event and returned to the bled to try and reconnect and find closure. Instead he finds that his father has been buried under another name and that he kept a box of memorabilia under his bed which contains Nazi memorabilia. What does this mean? Rachel is driven to get to the truth of his father's past, even if it means destroying his present. As Malrich reads about his brother's life, he also has to make decisions about his own. Should he let himself be persuaded by his brother's posthumous guilt? How should he live with the knowledge that his brother has given him?

Because of the setting and Islamic tie-ins, The German Mujahid is an unusual exploration of the post-Holocaust question of guilt and justice. Equally compelling is the story of these two brothers, linked by the diary. Never especially close growing up, the diary is a way for the brothers to communicate on a completely different level: Rachel revealed as vulnerable and confused, Malrich enabled to make decisions about his life. I found myself wanting to read as fast as I could to uncover the plot, and at the same time wanting to savor and ponder particular descriptions or philosophical questions. With the use of sticky notes and scraps of paper, I was able to do both, but it is definitely a book I see myself reading again. It was a perfect follow up to my reading The Good German, which deals with these questions from the German perspective. Instead of the immediate post-war period, however, is set a generation later, but continues to probe the essence of guilt, justice, and reparations.

10labfs39

We are on our own : a memoir by Miriam Katin

Published in 2006

Read in 2011

In 1944, Miriam is a bright and happy child living in Budapest with her mother and her dog Rexy. Her father, a dimly remembered figure, is away at the front. Miriam's mother, Esther, worries about the increasing restrictions on Jews, but Miriam's too young to understand the adults' fears. But when her dog is taken away and then they themselves have to move, Miriam struggles to make sense of her world and links their situation to her early lessons about God, often in a very literal way. On the run and relying on the protection of strangers, Miriam and Esther face loneliness, hunger, and fear over and over again during the next year. Finally the war ends, but it is still months before their journey ends.

The sketches in the book are mostly in black and white. Interspersed throughout, however, are a few pages in color. Most of these pages depict Miriam's perspective on her childhood as an adult, now with a child of her own. I found this juxtaposition to be particularly effective and easy to follow because of the use of color. The evolution of the child Miriam's concept of God during this horrible year is mirrored in the adult Miriam's struggles with religion and what she will teach her son. I found this strand of the story to be an important link between past and present, and representative of the effects of trauma on Miriam as an adult.

Miriam's memoir is also the story of her mother's bravery. The drawings of Esther portray a mother desperately trying to keep her daughter safe and, perhaps even harder, innocent. Visually seeing Esther's grief and despair, I leaped immediately to an emotional response, without needing to have it described in words. In a way her grief is beyond words. For me, this was the hardest part of the book to experience and the most beautiful.

11labfs39

Mendel's daughter by Martin Lemelman

Published 2006

Read 2009

Martin Lemelman videotaped his mother's rememberances of life before and during the Holocaust, then didn't look at it for years. After his mother's death, he used the videotapes to as the basis for this memoir, told in his mother's voice and illustrated in a graphic style reminiscent of Art Spiegelman's Maus, but without the frames. Occasionally his uncle's voice takes over the story, and I felt as though I were sitting around the kitchen table listening to my elders talk. It is a very accessible and appropriate for young adult readers as well as adults.

12labfs39

The war within these walls by Aline Sax (Author), Caryl Strzelecki (Illustrator), Laura Watkinson (Translator)

Published 2013

Read 2013

Powerful language combined with stark yet beautiful drawings make this short novel arresting. Although marketed as a young adult novel in the US, I found nothing juvenile about the treatment or the language.

Misha and his family are Polish Jews imprisoned in the Warsaw Ghetto by the Germans during the Holocaust. As more and more people are forced into the ghetto, the threat of starvation rises. Misha begins crossing to the Aryan side of the wall via the sewers to find food for his family. The knowledge of the underground passages serves him well when he joins a group of Jewish fighters determined to make the Germans pay when they come to liquidate the ghetto.

Similar to a graphic novel, the drawings are integral to the storytelling. Particularly moving was the juxtaposition of black text on white pages with the occasional black page with white text. Although the story of the Warsaw Uprising is well-known, this telling is worth reading for its visual and emotional impact.

13PaulCranswick

Thanks for setting up this group, Lisa.

My family doctor growing up lost virtually the whole of his family during the war in the extermination camps and something about the look in his eye when he talked about his mother has stayed with me forever.

I will try to read something most months.

My family doctor growing up lost virtually the whole of his family during the war in the extermination camps and something about the look in his eye when he talked about his mother has stayed with me forever.

I will try to read something most months.

14labfs39

>13 PaulCranswick: Welcome, Paul. After some interesting discussions at the end of last year about the Holocaust and based-on-a-true-story fiction, Kerry and I decided to set up a group. Already I have benefited, as I watched "Who Will Write Our History" last night and have added several titles and documentaries to my TBW/wish list.

The mother of my dad's Polish friend had a tattoo on her arm, and I remember as a kid trying, and failing, not to stare.

The mother of my dad's Polish friend had a tattoo on her arm, and I remember as a kid trying, and failing, not to stare.

15cbl_tn

Lots of good reading here. I've added several to my wishlist. It's interesting to me that, from what I've seen so far, there hasn't been a lot of overlap in any of our reading.

16labfs39

>15 cbl_tn: I was just on your thread too. Actually there are several overlaps, I haven't gotten as many of my books added yet. Stay tuned!

17labfs39

Beyond Courage: The Untold Story of Jewish Resistance During the Holocaust by Doreen Rappaport

Published 2012

Read 2013

I received this young adult book as a gift and was immediately delighted by the wealth of photographs. A diagram of the Bielski partisan camp in Naliboki Forest caught my eye, and I began reading. The book is arranged in several parts: realization, saving children, ghettos, camps, and partisan warfare. Each part contains the stories of several people: Jews and sometimes the Righteous Gentiles who risked their lives to help them. It appears the author tried to pick children and young people for inclusion, as often as possible, in order to further the book's appeal to young adults.

Some of the stories, such as that of the Bielski brothers, were already known to me. Others were known in their generality, if not particulars, like the Kindertransports. Still other accounts were completely new to me, such as the story of Mordechai "Motele" Gildenman, age 12, who spied on the Nazis in the guise of a cafe performer and later bombed the cafe.

While I enjoyed the book and value the photographs and accounts, I was a bit disappointed with the simplicity of the historical sections, which gave background information. Although not designed as a history of the Holocaust, I thought the glossing over of some of the complexities was a disservice to the reader. I was also disappointed to find that the photographs frequently used as background to the text were not reproduced elsewhere, such as in an appendix. I found myself straining to try and discern the subject of a photo, even when it was labeled, because it was so faint behind the text. It's a nice idea, I just wish the publishers had reproduced the photos elsewhere for better viewing.

Overall, I would still recommend the book, as I think the role of Jewish resistance, even if it is resistance in the form of escape or survival, is often minimized. Armed uprisings at death camps are often left out of Holocaust histories, I think because so few Jews survived them. But they are important, and their inclusion here might help young people get a more balanced picture of Jewish resistance and its cost.

18labfs39

Two Rings: A Story of Love and War by Millie Werber, Eve Keller

Published 2012

Read in 2012

Sometimes I fear that after having read so much about the Holocaust, I will begin to become numb to the personal tragedy as I try to grasp the enormity of the horror. Two Rings, however, is a personal narrative that cannot be read impersonally. Millie Werber is in her eighties, her husband has been gone for several years, and she has decided to share her story at last, for her children's sake and in the memory of her first love.

The story begins in Radom, a small city in Poland, where Millie lives a sheltered life with her parents and brother. In 1941, when the Germans create a ghetto for Jews, her family is forced to move into a small apartment, with her aunt, uncle, and two cousins. Millie is only fourteen and scared of everything: the hunger that won't go away, people in the streets being tortured at the whim of bored soldiers, and, most of all, the danger of being taken away by the Germans and never seen again. When her uncle finds her a potentially life-saving job at the Steyr-Daimler-Puch factory just outside of town, she is terrified. She has never slept apart from her mother or traveled. But her family forces her to go, and she begins a new chapter in her life, as a slave laborer in a Nazi ammunitions factory.

Barely fifteen, Millie is put to work at a huge machine for twelve hours a day, with only a fifteen minute break at noon. She cannot sit, rest, or make a mistake. As awful as it is, her job does save her, for in August 1942, the ghetto is liquidized. Fearing for her family and feeling terribly alone, Millie becomes friends with a young Jewish policeman who works in the factory. Heniek Greenspan is charming, slightly older, and solicitous of the women workers in his care. Millie and Heniek's relationship is a heart-warming, heart-breaking story of first love. Although their time together is brief, Millie never stops loving Heniek, not through her deportation to Auschwitz, and not through her wonderful marriage to Jack, with whom she spends 60 happy years.

To create this book, Millie told her story to Eve Keller, a professor and writer, whom she came to trust over a number of years. With patience and love, Keller worked to capture the story in Millie's own voice, and I think she does a wonderful job. The writing is simple and straightforward, conveying not only the mundane and the tragic, but also the fierce judgments that Millie does not try to hide. She tells her story as she remembers it, with strict, self-imposed honesty, and Keller gives the story to us with simple language and carefully verified details. The result is a beautiful story of a young girl, told with the thoughtfulness of age. I applaud Millie Gerber for her willingness to share such a personal memoir with us and Eve Keller for writing with such devotion. This is truly a remarkable book.

19labfs39

Rena's promise : a story of sisters in Auschwitz by Rena Kornreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam

Published 2015

Read 2015, reviewed 2021

Every Holocaust survivor memoir is a difficult but important read. When she was writing Rena′s Promise, Heather Macadam was asked, ″What′s it to you?″ I find that both an easy and difficult question to answer. To never forget. To honor those lost and those who survived. To try and understand. But I also feel a personal imperative that is difficult to put in words. It′s a self-directed reflection. What would I have done when faced with impossible choices? Where would I have fallen on the moral spectrum? Rena Kornreich′s focus was clear: everything she did and the choices she made were to save her little sister, Danka, and bring her home.

Rena was the third oldest of four sisters in a conservative Jewish family living in a small village in Poland. Danka was the baby of the family. When Nazi soldiers began harassing the girls, their parents sent them to stay with relatives in nearby Slovakia where conditions for Jews were slightly better. Unfortunately they ended up on the first registered transport of Jewish women to Auschwitz on March 25, 1942. The two sisters spent the next three years first in Auschwitz, then Birkenau. As liberating armies neared, they were forced on a death march to Ravensbruck in January 1945. These two facts—being on the first transport and surviving three years in the camps—make this memoir stand out from others, but the reason as to why they survived intrigues me too.

In The Train in Winter, Caroline Moorehead discusses how women who were communist were more likely to survive in prison and the concentration camps because they organized for each other. Similarly I think Rena survived in part because she was driven by the thought of bringing her baby sister home to her parents. Protecting her sister gave her a reason to life and continue to fight, when she might otherwise have given up. Nationality also played a cohesive role; several male Polish prisoners were instrumental in supplying the sisters with food and warmer clothing. Finding commonality was key to survival.

Although Rena′s Promise is of necessity dark, it was not a dismal read. Rena focuses on all the people that helped them: from Andrzej, who guided her across the border to Slovakia; to Emma, the work kapo who protected her; to Malek, the Polish captain who provided food and clothing. She also focuses on the love she found before, during, and after the war. Upon finishing the book, I was left with a feeling of hope and happiness, not despair. That's not always the case with these types of memoirs.

20labfs39

Sala's Gift: My Mother's Holocaust Story by Ann Kirschner

Published 2007

Read 2009

What makes this book remarkable is that the author's mother, Sala, was able to save all the letters from friends and family that she received throughout her five year ordeal in seven different labor camps. These letters, along with Sala's short diary, form the basis of the book and allow the reader to hear directly from the participants themselves at the time--rather than a retelling or telling many years later. The author fills in the context skillfully so that one doesn't feel jolted from letter to description. Altogether I was reminded of The Diary of Anne Frank. The voices of Sala and her sisters and friends reach out to us from the past in a way that is compelling, authentic, and innocent in the face of the horrors that descend upon them.

21labfs39

The road to rescue : the untold story of Schindler's list by Mieczysław Pemper, Viktoria Hertling, and Marie Elisabeth Müller, translated by David Dollenmayer

Published 2008

Read in 2008

Mietek Pemper's "Road to Rescue" is not a typical Holocaust memoir. There are few details about Pemper’s day to day life in the ghetto and later the camp. I didn't learn about what he ate or where he showered or his relationship with the others in his barracks. Instead it is the calm, unemotional accounting of his work as the clerk and stenographer to camp head, Amon Goth. The tone of the book itself is part of the story, for through it the reader is able to picture the type of man who could work with Goth for over 500 days without either being shot by Goth or having a complete breakdown from the pressure.

In addition to reflecting Pemper’s character, the tone of the book is also a calculated attempt to provide Holocaust deniers a foothold to begin picking at the accuracy of the book. In the preface he writes that “Even the tiniest details must be correct, for any imprecision threatens the credibility of the entire narrative. I am strictly opposed to exaggeration. In this book, I confine myself to telling the truth. I prefer to write a couple of words too few than one word too many.”

This tension between story and truth also defines his relationship with the juggernaut of “Schindler’s List”. Writing his book 15 years after Steven Spielberg’s movie was released, Pemper struggles to tell his story and take credit for his part in the saving of hundreds of lives, without appearing to be a latecomer looking for some of the fame. Between his extensive footnotes, documents from Schindler’s suitcase which wasn’t found until 1999 (after “Schindler’s List” was released), and testimony at the war crime trials of many Nazi’s including Amon Goth, Pemper succeeds in this, I think. In addition, Pemper is very careful not to tarnish Schindler’s memory. He writes that “Today, counting spouses, children, and grandchildren, more than six thousand people directly or indirectly owe their lives to Schindler. That’s what counts. Nothing else matters.”

Pemper sums up his experience as being what a journalist called “intelligent resistance”. A business and economics major, who taught himself German stenography, Pemper was not the sort to join bloody uprisings against the Nazi’s. But in his own quiet, unobtrusive way, he used his incredible visual memory and moral determination to save an entire camp from liquidation and the lives of hundreds of Jews. His is a remarkable story, and I am so glad he has shared it at last.

22cbl_tn

Two Rings and Sala's Gift have now been added to my Holocaust TBR list!

23labfs39

I Have Lived a Thousand Years: Growing Up in the Holocaust by Livia Bitton-Jackson

Published 1997, 224 p.

Read 2021

The author, née Elli Friedmann, was born in what is now Slovakia, but at the time was part of Hungary. At the age of thirteen, she, her mother, and older brother were deported to Auschwitz. Her father had been taken to a Hungarian labor camp. She and her mother are taken to Camp C, a half-built pen with no water. Within a couple of weeks, they are transferred to Camp Plaszow to work flattening hills by hand. Back to Auschwitz, then forced labor in Germany, prison camp, cattle cars to nowhere. It's a horrifying story, told very matter-of-factly. Unusual in that Elli was so young and that she survived particularly harsh treatment.

This book was written for young adults; the author has also written an adult memoir called Elli: Coming of Age in the Holocaust.

(edited to bold title)

24cbl_tn

>23 labfs39: My library has the YA one but not the one for adults. I added the YA title to my wishlist. I'm especially interested in memoirs of those who were at Dachau since that's the one camp I've visited.

25labfs39

>24 cbl_tn: I would have read the adult memoir, but my sister had this one, so I started with it. Elli was transported to the main camp at Dachau, but it was too full, and they got shuttled to Mühldorf, one of the satellite camps, and then were selected to go even further into the woods to a Waldlager where they lived in earthen bunkers underground. So not much about Dachau proper.

26labfs39

Five star reads that I never wrote reviews for:

Night by Elie Wiesel

The lost : a search for six of six millionby Daniel Adam Mendelsohn

Maus : a survivor's tale : my father bleeds history by Art Spiegelman

Maus II : a survivor's tale : and here my troubles began by Art Spiegelman

The Holocaust Chronicle edited by by David Aretha

I Never Saw Another Butterfly by Hana Volavkova

Others that I didn't review include:

The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition by Anne Frank

Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

Children of the Holocaust by Arnošt Lustig

If not now, when? by Primo Levi

The Cats in Krasinski Square by Karen Hesse

The Zookeeper's Wife: A War Story by Diane Ackerman

All but my life by Gerda Weissmann Klein

The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in United States Holocaust Memorial Museum by Michael Berenbaum

Malka by Mirjam Pressler

The True Story of Hansel and Gretel by Louise Murphy

Twilight : a novel by Elie Wiesel

Lovely Green Eyes: A Novel by Arnost Lustig

Mila 18 by Leon Uris

The secret Holocaust diaries : the untold story of Nonna Bannister by Nonna Bannister

Playing For Time by Fania Fenelon

Surviving Auschwitz: Children of the Shoah by Milton J. Nieuwsma

The Pianist: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man's Survival in Warsaw, 1939-1945 by Wladyslaw Szpilman

The Nazi Officer's Wife: How One Jewish Woman Survived the Holocaust by Edith H. Beer

Treblinka by Jean-François Steiner

Once, Then, Now by Morris Gleitzman

Fugitive Pieces: A Novel by Anne Michaels

A Thread of Grace by Mary Doria Russell

Night and Hope by Arnost Lustig

Schindler's List by Thomas Keneally

Sarah's key by Tatiana de Rosnay

Kindertransport by Olga Levy Drucker

The Periodic Table by Primo Levi

My Mother's Secret: A Novel Based on a True Holocaust Story by J. L. Witterick

The Upstairs Room by Johanna Reiss

Emotional Arithmetic by Matt Cohen

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas : a fable by John Boyne

The house of returned echoes by Arnošt Lustig

Auschwitz report by Primo Levi

Lily's crossing by Patricia Reilly Giff

The Unloved: From the Diary of Perla S. by Arnošt Lustig

The glass room by Simon Mawer

The emigrants by Winfried Georg Sebald

The Precious legacy : Judaic treasures from the Czechoslovak state collections by David A. Altshuler

The Holocaust: The World and the Jews, 1933-1945 by Seymour Rossel

Night by Elie Wiesel

The lost : a search for six of six millionby Daniel Adam Mendelsohn

Maus : a survivor's tale : my father bleeds history by Art Spiegelman

Maus II : a survivor's tale : and here my troubles began by Art Spiegelman

The Holocaust Chronicle edited by by David Aretha

I Never Saw Another Butterfly by Hana Volavkova

Others that I didn't review include:

The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition by Anne Frank

Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen

Children of the Holocaust by Arnošt Lustig

If not now, when? by Primo Levi

The Cats in Krasinski Square by Karen Hesse

The Zookeeper's Wife: A War Story by Diane Ackerman

All but my life by Gerda Weissmann Klein

The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in United States Holocaust Memorial Museum by Michael Berenbaum

Malka by Mirjam Pressler

The True Story of Hansel and Gretel by Louise Murphy

Twilight : a novel by Elie Wiesel

Lovely Green Eyes: A Novel by Arnost Lustig

Mila 18 by Leon Uris

The secret Holocaust diaries : the untold story of Nonna Bannister by Nonna Bannister

Playing For Time by Fania Fenelon

Surviving Auschwitz: Children of the Shoah by Milton J. Nieuwsma

The Pianist: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man's Survival in Warsaw, 1939-1945 by Wladyslaw Szpilman

The Nazi Officer's Wife: How One Jewish Woman Survived the Holocaust by Edith H. Beer

Treblinka by Jean-François Steiner

Once, Then, Now by Morris Gleitzman

Fugitive Pieces: A Novel by Anne Michaels

A Thread of Grace by Mary Doria Russell

Night and Hope by Arnost Lustig

Schindler's List by Thomas Keneally

Sarah's key by Tatiana de Rosnay

Kindertransport by Olga Levy Drucker

The Periodic Table by Primo Levi

My Mother's Secret: A Novel Based on a True Holocaust Story by J. L. Witterick

The Upstairs Room by Johanna Reiss

Emotional Arithmetic by Matt Cohen

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas : a fable by John Boyne

The house of returned echoes by Arnošt Lustig

Auschwitz report by Primo Levi

Lily's crossing by Patricia Reilly Giff

The Unloved: From the Diary of Perla S. by Arnošt Lustig

The glass room by Simon Mawer

The emigrants by Winfried Georg Sebald

The Precious legacy : Judaic treasures from the Czechoslovak state collections by David A. Altshuler

The Holocaust: The World and the Jews, 1933-1945 by Seymour Rossel

27rocketjk

>26 labfs39: I just caught up with your thread, here, Lisa. Thanks for all the heartfelt reviews. For me, Wiesel's Night is the one essential Holocaust memoir (though I haven't read nearly as many of these works as you have). I Never Saw Another Butterfly is the book that our teachers gave us in Hebrew school to try to impress upon us the sadness of life in the concentration camps for children.

28labfs39

>27 rocketjk: Thanks, Jerry. I am due a rereading of Night. Sadly all of my history, Holocaust, and memoir/bios books are still in boxes from my last move, so finding a particular title is a challenge. I would also like to find my copy of I Never Saw Another Butterfly to see if it includes artwork by Dita Krauss, whose memoir I read recently. She is one of the few children artists from Terezin who survived.

29labfs39

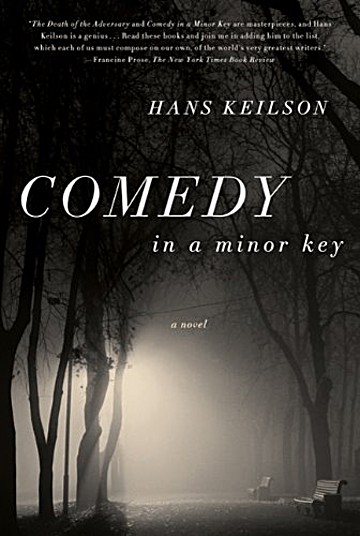

Comedy in a Minor Key by Hans Keilson translated from the German by Damion Searls

Originally published 1947, English translation 2010

Read 2014

This is the second the of the three novels written by Hans Keilson, a German Jew who escaped Germany in 1936 and joined the Dutch Resistance. His parents refused to go into hiding and were deported to Auschwitz where they were murdered. Hans did spend time in hiding, and this book reflects his understanding of the tensions inherent in long-term isolation, for both the hidden and the hiders.

Wim and Marie are an ordinary Dutch couple who take in and hide a Jewish man they know as Nico, not out of sympathy for the plight of Jews or a sense of humanism, but out of simple patriotism. The past year of hiding turns out to be easier than they expected, although not without its trials. But now they have a problem on their hands. Nico has died of pneumonia, and they need to get rid of the body.

In flashbacks, the author presents the tensions, misunderstandings, and growing compassion from both the perspective of the Dutch couple and the Jewish man they are hiding. What is great about this novella is not any extraordinary action or insight, but its average normalcy. This is the story of the unsung; no less courageous because of their lack of notoriety.

30labfs39

This book is different in that it is from the perspective of the child of a collaborator. I was reminded of it while rereading Maus.

Siberian exile : blood, war, and a granddaughter's reckoning by Julija Šukys

Published 2017

Read 2018

Julija Šukys is a Canadian of Lithuanian descent. The story of her family and her country were "tattooed on her skin," told and retold by family members and by the close-knit Lithuanian émigré population. Of these stories, she was particularly drawn to the story of her paternal grandmother, Ona. She always knew that someday she would write Ona's story and that is what she set out to do when writing this book.

Lithuania's history during WWII is complicated. They were invaded by the Russians, then the Germans, then the Russians again. Some citizens welcomed the Germans as saving them from the Russians, some welcomed the Russians for saving them from the Germans, some worked secretly against both. In 1941 Ona was taken from her apartment in the middle of the night by Soviet KGB officers and put on a cattle car for Siberia. Her crime? Being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or so the family said. One thing was for certain, her grandmother spent the next seventeen years in Siberia in a special settlement. It would be twenty-four years before she saw her husband or three children again.

This was the story Julija wanted to write: one of persecution overcome through tenacity and inner strength. Her grandmother's experience and survival was a story she wanted to pass on to her own son. But when she began researching her family's history, she found different story. One that included a perpetrator of violence, a collaborator with the Nazis. How to reconcile this long-hidden, incomprehensible reality with the stories she had been told and the family members she had known? What should she do with this knowledge? "Some always pays," she writes. "The question is who. And the question is how." Was she herself somehow tainted and culpable through association, through heredity? Was she somehow paying, now, with this new unwanted knowledge? Could she atone? Should she?

I found all of these questions fascinating and, for me, they were as compelling as the story of Julija's grandparents. Their experiences in Lithuania and Siberia were unique, and yet representative of the complexities of the region dubbed by Timothy Snyder as "the Bloodlands." And Julija's struggles, as a writer and a member of a family and close community, to make sense of these experiences is again both uniquely her own and representative of an entire country's struggle to understand collaboration, violence, and the desire to put the past in the past.

Julija Šukys lays open her family's history as a testament to the value of truth and as an act of redemption. The tone is rough and captures the sense of pain tightly controlled, but at the same time it is not unrelenting darkness. The story of Ona still shines through as the family history that Julija had always wanted to write.

Siberian exile : blood, war, and a granddaughter's reckoning by Julija Šukys

Published 2017

Read 2018

Julija Šukys is a Canadian of Lithuanian descent. The story of her family and her country were "tattooed on her skin," told and retold by family members and by the close-knit Lithuanian émigré population. Of these stories, she was particularly drawn to the story of her paternal grandmother, Ona. She always knew that someday she would write Ona's story and that is what she set out to do when writing this book.

Lithuania's history during WWII is complicated. They were invaded by the Russians, then the Germans, then the Russians again. Some citizens welcomed the Germans as saving them from the Russians, some welcomed the Russians for saving them from the Germans, some worked secretly against both. In 1941 Ona was taken from her apartment in the middle of the night by Soviet KGB officers and put on a cattle car for Siberia. Her crime? Being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or so the family said. One thing was for certain, her grandmother spent the next seventeen years in Siberia in a special settlement. It would be twenty-four years before she saw her husband or three children again.

This was the story Julija wanted to write: one of persecution overcome through tenacity and inner strength. Her grandmother's experience and survival was a story she wanted to pass on to her own son. But when she began researching her family's history, she found different story. One that included a perpetrator of violence, a collaborator with the Nazis. How to reconcile this long-hidden, incomprehensible reality with the stories she had been told and the family members she had known? What should she do with this knowledge? "Some always pays," she writes. "The question is who. And the question is how." Was she herself somehow tainted and culpable through association, through heredity? Was she somehow paying, now, with this new unwanted knowledge? Could she atone? Should she?

I found all of these questions fascinating and, for me, they were as compelling as the story of Julija's grandparents. Their experiences in Lithuania and Siberia were unique, and yet representative of the complexities of the region dubbed by Timothy Snyder as "the Bloodlands." And Julija's struggles, as a writer and a member of a family and close community, to make sense of these experiences is again both uniquely her own and representative of an entire country's struggle to understand collaboration, violence, and the desire to put the past in the past.

Julija Šukys lays open her family's history as a testament to the value of truth and as an act of redemption. The tone is rough and captures the sense of pain tightly controlled, but at the same time it is not unrelenting darkness. The story of Ona still shines through as the family history that Julija had always wanted to write.

31labfs39

Lauren Yanofsky Hates the Holocaust by Leanne Lieberman

Published 2013

Read 2013

Lauren Yanofsky is a typical eleventh grader: she has a crush on her biology partner, is upset that her best friend is hanging out with a new clique, and thinks her parents are clueless. But she's unique as well. Her father is a Holocaust professor and for a while, she read everything she could about the Holocaust. But after she started having panic attacks, she not only stopped wanting to hear anything about the subject, but decided to "de-convert" from being Jewish, not a decision easily accepted by her parents. When she catches the impossibly desirable Jesse playing Nazis in the park with some boys, her tenuous grip on her relationship with the Holocaust is caught in the cross hairs. How bad is the boys' game? Can she still like someone who would play Nazi? Should she tell?

This was a quick and quirky read by Canadian author, Leanne Lieberman. I personally had some problems with the drinking, smoking, and lying to the parents, but the situation Lauren finds herself in is one that I would like to discuss with my own daughter. Where is the border between stupid and anti-Semitic? What do you do when someone you like does something wrong? And how do you balance a Jewish identity with an American childhood?

This is a young adult book that I received through the Early Reviewers program.

32labfs39

Those Who Save Us by Jenna Blum

Published 2004

Read 2008

I've read a fair number of memoirs and other non-fiction about the Holocaust and am always hesitant about reading fiction in this area. After all, the truth is haunting enough without embellishment. But occasionally a Holocaust novel will move beyond the devices of plot and illuminate some fundamental human emotions and questions that are true regardless of whether they actually happened. Arnošt Lustig comes immediately to mind as one with the ability to translate his experiences through the lens of fiction and emerge with something even greater. I am reminded in particular of his Lovely Green Eyes. Blum's characters deal with issues that provoke both an emotional response and contemplation. What does it mean to love those who save us, or shame us? How do brutal experiences change a person's ability to love or even to remember love? What does it mean to protect your child at the expense of your own soul? Is it possible to find peace if you are denied any possibility of acceptance?

33avatiakh

>31 labfs39: I read this one 4 or 5 years ago, my comments included...'It's a mixed bag sort of read, one I would have abandoned except I decided to finish it to see where Lauren ends up....I suppose when I read YA Jewish fiction I want the main character to accept their Jewish identity and be stronger for it.'

34labfs39

>33 avatiakh: Ideally, from my perspective, I agree. I would like teens to "accept their Jewish identity and be stronger for it," but I'm not sure that is the lived experience for all teens. I think some American Jewish teens (and evidently Canadian) struggle with the weight of the Holocaust and the conflict that can arise between the desire to be a good Jew and the desire to fit into a secular society. Throw in some teen rebellion, and it's not always a pretty picture. I read this eight or nine years ago, but my lingering impression is that although I understood what the author was trying to do, I'm not sure it was the best execution.

35labfs39

Second Generation: Things I Didn't Tell My Father by Michel Kichka, translated from the French by Montana Kane

Originally published 2012, Eng. translation 2016, 105 p.

Michel Kichka is an Israeli cartoonist and illustrator who was born and raised in Belgium. His father, Henri Kichka, was a survivor of Buchenwald and a well-known and respected educator on the Holocaust. Second Generation is the story of their relationship.

Michel's childhood was defined in part by the Holocaust. He spent hours looking through his father's books on the Shoah searching for pictures of family members and fearing he would see his teenage father in the photos. His father saw Michel's good grades and achievements as a way to get back at Hitler, and Michel and his siblings felt a constant pressure to be the perfect family. Years later while talking to his sister, he thinks that it was "as if we weren't entitled to teenage angst because Hitler robbed him of his."

Michel moves to Israel, graduates from art school, marries, and has children of his own, but the Holocaust still shadows his life and family. His brother-in-law commits suicide and three months later his brother does too. The shock of losing his brother sends Michel into a tailspin, and a floodgate is opened in his father's memories. Henri writes his memoirs, Une adolescence perdue dans la nuit des camps and begins teaching about the Holocaust and leading groups to Auschwitz. Michel wonders, "I sometimes feel that his testimony has replaced his memory... His death march has been going on for 67 years. He walks on while his deceased loved ones pile up behind him."

36avatiakh

>35 labfs39: This sounds like an interesting read. I've also noted his Falafel with hot sauce.

37labfs39

>36 avatiakh: It has a lot of parallels of course to Maus and Art Spiegelman, but I found Kichka's writing to be more poetic. I didn't feel the urge to write down any lines while reading Maus, but I did with this book. I would like to read Henri Kichka's memoir too.

38labfs39

The Property by Rutu Modan, translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen

Published 2013, 222 pages

With family, you don't have to tell the whole truth and it's not considered lying.

-Michaela Modan, epigraph

Mica accompanies her grandmother to Warsaw from Israel, purportedly to recover a family apartment that was confiscated during the Holocaust. Once there, however, Mica begins to suspect that her grandmother has a different motive for the trip. The Property features strong women, humor with a touch of sarcasm, and understated motifs that are more powerful for the lack of heavy-handedness.

The illustrations in this graphic novel are at times blocky and at times finely detailed, with wonderful expressiveness. The colors are muted with lots of maroon, black, and mustard. The text is translated into block letters for Hebrew, italics for Polish, and mixed case for English. When Mica doesn't understand what people are saying, the text is just squiggles. The artwork complements the story well.

39labfs39

Daughters of the Occupation: A Novel of WWII by Shelly Sanders

Published 2022, 364 p.

Sarah's estranged grandmother, Miriam, appears at her mother's funeral and speaks in Hebrew over the casket. Her grandmother was Jewish? Why had her mother and grandmother fallen out? What other secrets did her family hold? Sarah decides to overcome her grandmother's reluctance and learn her family's history. Her investigation leads her to Riga, Latvia in search of a relative who had been left behind when her mother and grandmother fled to America after the war.

Miriam's and Sarah's stories are told in alternating chapters, the former starting in Riga in 1940 and the latter in Chicago in 1975. Loosely based on experiences that members of the author's family had during the war, the novel includes the infamous Rumbula Forest massacre, the successive occupations by the Soviets and Nazis, and life during the 1970s in communist Riga. Fast-paced, it's a quick read, and I enjoyed the afterward by the author which includes a few photos.

To simplify the narrative, the main character experiences almost every aspect of the Latvian Holocaust personally. At times this felt a bit contrived, although taken individually the events are accurate. Overall it was an interesting introduction to the Latvian Holocaust, and the bibliography provides readers an opportunity to learn more.

40cbl_tn

>39 labfs39: That sounds interesting. One of my public libraries has copies in several formats so I've added it to my library wishlist.

41labfs39

>40 cbl_tn: It was a novel, and I always have qualms about reading fiction about the Holocaust, but I didn't know a lot about the situation in Latvia, and it did provide some background that way. I'll be curious as to your take, if/when you get to it.

42cbl_tn

>41 labfs39: I feel the same way about Holocaust fiction, but I'm willing to give this one a try since you didn't hate it. The author may not have had enough material on the family's experience to write a nonfiction account, and fiction allowed for filling in the gaps.

43cindydavid4

I know very little of the Baltic experience during the Holocaust, learned some from Ericka Fatlands book the border Its made me want to read further, this might be a good place to start

44labfs39

>42 cbl_tn: True, Carrie. In response to a poster, I wrote this over on my thread this morning.

When it comes to Holocaust literature, I almost always say nonfiction. An exception is fiction written by someone like Arnošt Lustig or Primo Levi. However, as we get further removed in time from the Holocaust, there are fewer survivors to write about it. Does that mean no more Holocaust literature should be written? Well, no, so I find myself looking more at books written by the survivors' children. In this case, like one of her main characters, the author didn't find out she was Jewish until she was an adult. She then began researching and found out she lost 23 members of her family in the Holocaust (others were deported to Siberia by the Soviets, which is where her grandmother was born). Perhaps I'm too fastidious, but I try to avoid books written by lookie-loos.

I almost wish this author had written a family memoir, as I would like to have learned more about her grandmother's experience in Siberia, but as you say, she may not have had enough material.

When it comes to Holocaust literature, I almost always say nonfiction. An exception is fiction written by someone like Arnošt Lustig or Primo Levi. However, as we get further removed in time from the Holocaust, there are fewer survivors to write about it. Does that mean no more Holocaust literature should be written? Well, no, so I find myself looking more at books written by the survivors' children. In this case, like one of her main characters, the author didn't find out she was Jewish until she was an adult. She then began researching and found out she lost 23 members of her family in the Holocaust (others were deported to Siberia by the Soviets, which is where her grandmother was born). Perhaps I'm too fastidious, but I try to avoid books written by lookie-loos.

I almost wish this author had written a family memoir, as I would like to have learned more about her grandmother's experience in Siberia, but as you say, she may not have had enough material.

45labfs39

>43 cindydavid4: I too know less about the Holocaust in the Baltic countries. One I would recommend, however, is Siberian exile : blood, war, and a granddaughter's reckoning by Julija Šukys. Šukys set out to write just such a memoir as I mentioned above (her grandmother was deported to Siberia from Lithuania in 1941), but as she researched her family she uncovered a lot of secrets, including the fact that one of her grandparents was a collaborator. Her book talks not only about what she learned, but about how she felt upon learned she was the granddaughter of someone complicit in the murder of Jews. My review is here.

46rocketjk

>45 labfs39: I just read your review of Siberian Exile. Fascinating, and I'll look out for that book.

47labfs39

>46 rocketjk: It was very interesting. I attended an author talk at the Decatur Book Festival a few years ago and was intrigued by her story. I read another book by her, Epistolophilia : writing the life of Ona Šimaitė, but didn't care for it as much. I posted a review on my thread, but not on the book page. I wrote:

It's about a Lithuanian librarian who helps rescue Jews from the Vilna Ghetto. She is caught by the Gestapo, tortured, and sent to camps. She spends the rest of her life in Paris and Israel, writing copious numbers of letters to her friends, family, and colleagues.

Although the premise was promising, it was not the book I was expecting. Ona's life, which sounds so fascinating, is left with gaping holes. Nothing of her time with the Gestapo or in camps is known, no interviews flesh out her personality, only excerpts of her letters are left to outline her life and inner world. The subtitle is a more telling description of the book, "Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė." This is as much the author's story as Ona's. The author does offer some insights into the nature of letter writing and the writing of women's stories, but as a biography, the book disappoints.

The author includes a chapter called "Librarians," in which she denigrates the work that women do in libraries, especially that of catalogers, "the lowest of the lows." She writes, "Cataloging requires attention to detail and the endurance of boredom, repetitive work, and even pain--characteristics traditionally considered to be feminine." I'm not sure how many catalogers she has known, but having been one myself, I must disagree and say that the organization of knowledge into discrete categories, assigning metadata so that users can find and access the information they need when they need it, and exploring books to discover and share the knowledge they contain is hardly a boring profession. Having done a lot of other jobs in the information sector, I would go back to being a cataloger anytime. Aren't we all on LT catalogers in our own ways? Are you in pain?

Clearly it rubbed me the wrong way.

It's about a Lithuanian librarian who helps rescue Jews from the Vilna Ghetto. She is caught by the Gestapo, tortured, and sent to camps. She spends the rest of her life in Paris and Israel, writing copious numbers of letters to her friends, family, and colleagues.

Although the premise was promising, it was not the book I was expecting. Ona's life, which sounds so fascinating, is left with gaping holes. Nothing of her time with the Gestapo or in camps is known, no interviews flesh out her personality, only excerpts of her letters are left to outline her life and inner world. The subtitle is a more telling description of the book, "Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė." This is as much the author's story as Ona's. The author does offer some insights into the nature of letter writing and the writing of women's stories, but as a biography, the book disappoints.

The author includes a chapter called "Librarians," in which she denigrates the work that women do in libraries, especially that of catalogers, "the lowest of the lows." She writes, "Cataloging requires attention to detail and the endurance of boredom, repetitive work, and even pain--characteristics traditionally considered to be feminine." I'm not sure how many catalogers she has known, but having been one myself, I must disagree and say that the organization of knowledge into discrete categories, assigning metadata so that users can find and access the information they need when they need it, and exploring books to discover and share the knowledge they contain is hardly a boring profession. Having done a lot of other jobs in the information sector, I would go back to being a cataloger anytime. Aren't we all on LT catalogers in our own ways? Are you in pain?

Clearly it rubbed me the wrong way.

48cindydavid4

wow its been quiet here; anyone still around? Has anyone read like a river from its course thinking about reading this for our harvest moon thread thinking about sept and the high holy days, when the attack on babi yar took place . I am hesitating because I am already well aware of the story, via my family and have the newly translated Yizkor book from our village Sarny. Do you think anything will be gained from reading this?

49labfs39

>48 cindydavid4: Hi Cindy. I have been remiss in my Holocaust reading lately. I'm afraid much of my reading bandwidth has been taken up with books for the Asian Book Challenge. I will try to read something soon, especially with the High Holidays coming up.

50labfs39

This was an Early Reviewer privately-published book.

Romek's Lost Youth: The Story of a Boy Survivor by Ken Roman and John James

Published 2022, 120 p.

Roman, or Romek, as his family called him, was only 13 when Germany invaded his native Poland. He was an only child, but part of a large, close-knit family who owned a soda factory in Gorlice. In 1941 he was apprenticed to a Silesian engineer who owned a small fix-it shop, in an attempt to keep him from being abducted for forced labor by the Germans. Blond, blue-eyed, and fluent in Polish (not all Jews of the time were), Romek began passing as Polish. Then the Judenrat submitted his name to the Gestapo as skilled labor, and he was assigned to a nearby Luftwaffe facility. The sixty workers at the facility were saved during the final action, when the Jews of Gorlice were rounded up. Many of the Jews were shot in a nearby brick factory, the rest sent to the camps. Of the 42 members of Romek's family, only he and his uncle survived the Holocaust.