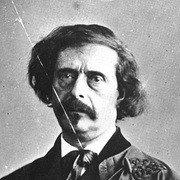

Jules Barbey d'AurevillyBesprekingen

Auteur van Duivelinnen en demonen

107+ Werken 1,403 Leden 31 Besprekingen Favoriet van 10 leden

Besprekingen

Gemarkeerd

franderochefort | 11 andere besprekingen | Aug 5, 2023 | XIX. századi francia próza, időutazóknak való. Barbey d'Aurevilly történeteire jellemző, hogy az író-elbeszélő mintegy kiemeli magát a cselekményből azzal, hogy az nem vele, hanem valaki mással történt meg: egy ismerőssel, aki egy postakocsiban, vagy egy parkbéli padon ülve meséli el azt. Ez a módszer egyszersmind valamiféle finom időtlenséget is áraszt magából – lám, akkor még volt mód és idő arra, hogy egy barátra órákon át záporoztassuk azt, mi szívünket nyomja. (Franciás szellemességgel, persze.) Manapság az ilyen barátot pszichológusnak hívják, és szemrebbenés nélkül kiszámlázza a vele töltött időt. Ez tehát az, ami ismerős a korszak irodalmából, de akadt olyasmi is, amivel sikerült meglepnie.

Barbey d'Aurevilly irományainak egyik legsajátosabb eleme: a női főszereplő. Ezek a pompás termetű nőstény párducok, akik a magamfajta szende csávókat simán megennék reggelire, fokhagymás tejföllel. (Hogy, hogy nem, de úgy képzelem el őket, mint a női kajakozókat. Nem tudom, valaki látott-e már női kajakozóhoz tartozó hátat.) Írónknak valószínűleg holmi traumatikus élményei lehettek egy hasonló nőszeméllyel (tévedés lenne őt hölgynek nevezni), mert leitmotivként kísérik végig az életművet. Ennél is meglepőbb volt azonban az a nyíltság, mi több, helyenként brutalitás, ahogy Barbey d'Aurevilly a testiséggel, az erőszakkal kapcsolatban megnyilatkozik. (Nem csoda, hogy betiltották anno – inkább az a különös, hogy végül engedélyezték.) Különösen a kötet utolsó elbeszélése (Egy asszony bosszúja) gázol térdig a mocsokban* – és jól áll neki. Több, mint figyelemre méltó író.

* No persze nem mondjuk Irvine Welsh-hez viszonyítva. Hanem csak úgy Daudet-hez.

Barbey d'Aurevilly irományainak egyik legsajátosabb eleme: a női főszereplő. Ezek a pompás termetű nőstény párducok, akik a magamfajta szende csávókat simán megennék reggelire, fokhagymás tejföllel. (Hogy, hogy nem, de úgy képzelem el őket, mint a női kajakozókat. Nem tudom, valaki látott-e már női kajakozóhoz tartozó hátat.) Írónknak valószínűleg holmi traumatikus élményei lehettek egy hasonló nőszeméllyel (tévedés lenne őt hölgynek nevezni), mert leitmotivként kísérik végig az életművet. Ennél is meglepőbb volt azonban az a nyíltság, mi több, helyenként brutalitás, ahogy Barbey d'Aurevilly a testiséggel, az erőszakkal kapcsolatban megnyilatkozik. (Nem csoda, hogy betiltották anno – inkább az a különös, hogy végül engedélyezték.) Különösen a kötet utolsó elbeszélése (Egy asszony bosszúja) gázol térdig a mocsokban* – és jól áll neki. Több, mint figyelemre méltó író.

* No persze nem mondjuk Irvine Welsh-hez viszonyítva. Hanem csak úgy Daudet-hez.

Gemarkeerd

Kuszma | Jul 2, 2022 | This book contains two stories from Barbey d’Aurevilly’s 1874 collection Les diaboliques, which centre around women who exact vengeance or who commit crimes while in pursuit of their own goals.

One story is about a group of upper-class nobles who spend their days playing whist -- from 9am to 5pm, every day. Consequently, they’re very good at it, and their poker-faces and experienced game-play allow for covert drama to unfold during games. The second story is about an uncommonly pretty prostitute, who is eager to tell one of her clients her backstory.

I would call these stories interesting rather than engrossing, mainly because it seems they were written with different standards in mind for how short stories work. Neither story here features a traditional tension arc, for one thing: much of one story is taken up with descriptions of looks, character and habits, with thegruesome conclusion taking up only a few lines. Also, the meat of both stories is kept at various removes, told as it is to the main character by someone else in-universe, and sometimes main points are relayed through reported speech within that story. The sensitivities and cultural touchstones are those of the upper-class French during the early eighteen-hundreds, and d’Aurevilly’s tales seem to be as much about his audience (or about the societal class of people his stories are set among) as they are about narrating a plot.

One story is about a group of upper-class nobles who spend their days playing whist -- from 9am to 5pm, every day. Consequently, they’re very good at it, and their poker-faces and experienced game-play allow for covert drama to unfold during games. The second story is about an uncommonly pretty prostitute, who is eager to tell one of her clients her backstory.

I would call these stories interesting rather than engrossing, mainly because it seems they were written with different standards in mind for how short stories work. Neither story here features a traditional tension arc, for one thing: much of one story is taken up with descriptions of looks, character and habits, with the

Gemarkeerd

Petroglyph | Jan 4, 2020 | Le Bonheur dans le crime est l’une des plus célèbres des six nouvelles du sulfureux recueil Les Diaboliques – qui a valu à Barbey d’Aurevilly d’être accusé d’immoralisme et de sadisme.

Écrite vers 1870, cette histoire cynique et amorale (“c’est à croire que le Diable a dicté”) raconte la passion adultérine dévorante qui unit le comte Serlon de Savigny à la belle Hauteclaire Stassin, maîtresse d’armes avec qui il aime à croiser le fer. Mais le comte est marié…

Hauteclaire, avec la complicité du comte, envisage alors un plan diabolique pour se débarrasser de sa rivale.

Quelques années plus tard, les deux amants s'unissent par un mariage – forcément honteux.

Mais ce terrible crime viendra-t-il corrompre leur amour ? Bonheur et crime sont-ils conciliables ?

La conclusion de l'histoire est “à terrasser […] tous les moralistes de la terre, qui ont inventé le bel axiome du vice puni et de la vertu récompensée” puisque le nouveau couple devient au fil du temps un “modèle fabuleux d’amour conjugal” ! Et le narrateur doit avouer qu'il a bien cherché, mais que, dans “leur étonnant et révoltant bonheur”, il n'a “jamais rien trouvé qu’une félicité à faire envie, et qui serait une excellente et triomphante plaisanterie du Diable contre Dieu, s’il y avait un Dieu et un Diable !”

Le texte est suivi d'une notice biographique de Bernadette Dubois.

Cette nouvelle a été adaptée pour la télévision par France 2, dans le cadre de la série Au siècle de Maupassant : contes et nouvelles du XIXe siècle. Le film a été diffusé le mardi 17 mars 2009, avec comme acteurs Didier Bourdon, Grégori Derangère et Marie Kremer.

Écrite vers 1870, cette histoire cynique et amorale (“c’est à croire que le Diable a dicté”) raconte la passion adultérine dévorante qui unit le comte Serlon de Savigny à la belle Hauteclaire Stassin, maîtresse d’armes avec qui il aime à croiser le fer. Mais le comte est marié…

Hauteclaire, avec la complicité du comte, envisage alors un plan diabolique pour se débarrasser de sa rivale.

Quelques années plus tard, les deux amants s'unissent par un mariage – forcément honteux.

Mais ce terrible crime viendra-t-il corrompre leur amour ? Bonheur et crime sont-ils conciliables ?

La conclusion de l'histoire est “à terrasser […] tous les moralistes de la terre, qui ont inventé le bel axiome du vice puni et de la vertu récompensée” puisque le nouveau couple devient au fil du temps un “modèle fabuleux d’amour conjugal” ! Et le narrateur doit avouer qu'il a bien cherché, mais que, dans “leur étonnant et révoltant bonheur”, il n'a “jamais rien trouvé qu’une félicité à faire envie, et qui serait une excellente et triomphante plaisanterie du Diable contre Dieu, s’il y avait un Dieu et un Diable !”

Le texte est suivi d'une notice biographique de Bernadette Dubois.

Cette nouvelle a été adaptée pour la télévision par France 2, dans le cadre de la série Au siècle de Maupassant : contes et nouvelles du XIXe siècle. Le film a été diffusé le mardi 17 mars 2009, avec comme acteurs Didier Bourdon, Grégori Derangère et Marie Kremer.

Gemarkeerd

Haijavivi | 1 andere bespreking | Jun 7, 2019 | > Etudes de moeurs, fables amorales ou simples provocations ? Les six nouvelles qui composent Les Diaboliques auront en tout état de cause valu à leur auteur un procès pour "outrage à la morale publique" lors de leur parution en 1874. Barbey, dandy post-romantique à la plume acérée, déclare dans sa première préface à l'ouvrage n'avoir rien inventé... "Les histoires sont vraies", écrit-il. Le corps social aura donc - si l'on en croit l'auteur - mal supporté d'être mis en face de son propre bourbier. Il s'agit là de trahisons, de luxure, de machiavélisme mais également de crimes de sang. Plus généralement, Barbey explore dans ses récits le pendant morbide et la capacité destructrice des passions humaines, tout autant que la plénitude apportée aux criminels par certains de leurs forfaits. Les amants coupables de la nouvelle intitulée Le Bonheur dans le crime sont à ce titre scandaleux aux yeux de la bienséance : qu'il ait fallu, pour vivre leur amour, éliminer physiquement l'épouse indésirable, ne les empêche en rien d'accéder à un bonheur quasi surnaturel. L'âme humaine est ici traitée sans condescendance et les six "autopsies" que livre Barbey sont servies par une écriture flamboyante ainsi que par un sens aiguisé du mystère.

--Lenaïc Gravis et Jocelyn Blériot, Amazon.fr

> Par Adrian (Laculturegenerale.com) : Les 150 classiques de la littérature française qu’il faut avoir lus !

07/05/2017 - Barbey d’Aurevilly essaiera de vous montrer que oui, le surnaturel existe toujours dans notre monde moderne. Si vous souhaitez lire un auteur au style déroutant, attiré par Satan, dirigez-vous vers ce recueil de nouvelles !

--Lenaïc Gravis et Jocelyn Blériot, Amazon.fr

> Par Adrian (Laculturegenerale.com) : Les 150 classiques de la littérature française qu’il faut avoir lus !

07/05/2017 - Barbey d’Aurevilly essaiera de vous montrer que oui, le surnaturel existe toujours dans notre monde moderne. Si vous souhaitez lire un auteur au style déroutant, attiré par Satan, dirigez-vous vers ce recueil de nouvelles !

Gemarkeerd

Joop-le-philosophe | 11 andere besprekingen | Jan 27, 2019 | Je me souviens avoir ouvert un Barbey d’Aurevilly dans mes prudes jeunes années et l’avoir refermé presque aussi vite devant tant de décadence. Avec cette longue nouvelle extraites des Diaboliques, je retrouve cet auteur, maintenant que je suis plus aguerrie, ou du moins plus aussi naïve.

Cela reste conforme à mon souvenir. Toujours sur le fil du rasoir : on ne tombe jamais dans la vulgarité, mais c’est plein de passions plus ou moins contenues, plus ou moins avouables. J’ai pris plaisir à cette redécouverte, mais je pense qu’elle est suffisante pour moi, tout simplement pas le genre de littérature qui m’intéresse.

Cela reste conforme à mon souvenir. Toujours sur le fil du rasoir : on ne tombe jamais dans la vulgarité, mais c’est plein de passions plus ou moins contenues, plus ou moins avouables. J’ai pris plaisir à cette redécouverte, mais je pense qu’elle est suffisante pour moi, tout simplement pas le genre de littérature qui m’intéresse.

Gemarkeerd

raton-liseur | Jan 7, 2019 | Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly (1808 – 1889), romantic with the sensibility of a decadent , self-styled dandy, teller of risqué novels and short stories, shocked readers and infuriated the authorities with the publication of Les Diaboliques. But there is much more to this captivating novel with its sumptuous, elegant language, well-crafted metaphors and highly visual and sensual imagery than simply shock value. Below are a number of themes common to the six separate tales comprising this novel:

Story within a story

For example, in The Crimson Curtain, the first-person narrator tells us as readers how one evening years ago while returning from a hunting trip he shared a carriage with a rotund, old dandy he calls Vicomte de Brassard. The carriage made a stop in a small provincial town for repair. Gazing up at an upper-story window of one of the town’s large buildings, a crimson curtain caught the narrator’s attention; he points out the captivating tint of the curtain to his riding companion. Ah, such are the twists of fate, since, as it turns out, that exact room with the crimson curtain was a dramatic marker for de Brassard’s life -- it all happened back in the day when he was but a seventeen-year-old sublieutenant. And dandy de Brassard tells the tale.

Storytelling with a hook

There’s a point, usually about half way through, when something unexpected happens to propel the story into overdrive. And what variety of event are we alluding to here? Why, of course, as if lighting a fuse to a stick of dynamite, a woman ignites a man’s passion: BOOM! Now we’re reading a Barbey-d’Aurevilly-style spellbinding page-turner.

Dandyism

For Barbey d’Aurevilly, a dandy is not only a man scrupulously devoted to style, neatness and fashion but, as he describes Vicomte de Brassard, a dandy has a seductive beauty which seduce not only woman but circumstances themselves; has a careless disdain and repugnance of discipline; keeps several mistresses at the same time like seven strings of his lyre; drinks like a Pole; jests about his own immorality; belongs to his own times and transcends his times; and, lastly, above all else, scorns all emotion as being beneath him.

Conversation as a cultural highpoint

In all six of these Barbey d’Aurevilly tales, the characters raise conversation to an art form – probing inquiry; genteel exchange; elaborate, detailed storytelling with all the necessary color and nuance to convey a vivid, sensual picture; and, above all, a deep respect for the speaker, permitting one’s interlocutor time and space – none of those spurious interruptions commonplace in our current world: cutting a speaker off mid-sentence, answering cell-phones, texting, checking emails, looking at one’s watch (the ultimate insult). Indeed, engaging in conversation as a cultivated skill, a consummate refinement, similar to playing baroque music or painting in oils.

Woman as the real power player

19th century France: Victorian, bourgeois, patriarchal, or, in other words, a male-centered, conservative, reason-dominated society. But the dirty little secret for the upholders of Victorian patriarchy is our all-too-human life is fueled by passion and emotion, most particularly sexual emotion – sexual attraction, sexual arousal and, of course, erotic love. The power of each of these Barbey d’Aurevilly tales lies in the fact a female instigates or initiates the key action. Talk about turning those Victorian values upside down and shaking! No wonder the authorities hated Barbey d’Aurevilly and banned his 1874 novel – Les Diaboliques also gave the French reading public one of its first tastes of what came to be known as the Decadent Movement, with its smashing to bits the connection and linking of virtue/reward, vice/punishment, good morals/happiness and bad morals/unhappiness, as in Happiness in Crime, a tale of two adulterers and murderers who live happily ever after.

For a more specific rasa, let’s look at one of the tales. In The Greatest Love of Don Juan, we read of a Don Juan-like lover, Comte de Ravila, dining with twelve of his previous romantic conquests. Barbey d’Aurevilly describes the physical strength and mature sensuality of these sumptuous lovers: “Full curves and ample proportions, dazzling bosoms, beating in majestic swells above liberally cut bodices . . . “ And then he writes of the sheer psychic power of these ladies as the evening progresses: “They felt a new and mysterious power in their innermost being of which, until then, they had never suspected the existence. The joy of this discovery, the sensation of a tripled life force, the physical incitements, so stimulating to highly strung temperaments, the sparkling lights, the penetrating odor of so many flowers swooning in an atmosphere overheated with the emanations of all these lovely bodies, the sting of heady wines, all acted together.”

Then, one woman demands our Don Juan tell the story of the greatest love of his life. If effect, he is being asked to choose one of his lovers amongst the present company. Comte de Ravila tells his story but, turns out, the story is not at all what these ladies expected.

My take is Ravila did the exactly the right thing. True, his story was not a tale of wild, heart-stopping, hot-blooded passion – he probably had twelve equally erotic and fantastically romantic stories to tell on that subject, one for each lady present, however his story was of a completely different cast but a story that had, from his perspective, a happy ending – he escaped from the banquet with the real prize: his life.

What an impossible question to ask a man: to choose one woman amongst twelve surrounding him. If he did, he most likely would have been torn to shreds by eleven Dionysian-frenzied former lovers. That’s the way to think on your feet and save your skin, Ravila. Bravo!

Gemarkeerd

Glenn_Russell | 11 andere besprekingen | Nov 13, 2018 | It is indeed funny, how this book combines the genuine horror of a young officer whose hand has been touched by a hand of a young woman under the dinner table in the first novella (Le rideau cramoisi) with the graphic mutilation and torture scenes, or with eighty nuns raped by two escadrons and thrown into a well while still alive in the last novellas.

Style sample (makes me wanna turn it into an intertitle in a silent film): "Notre amour avait eu la simultanéité de deux coups de pistolet tirés en même temps, et qui tuent…"

The first four stories really make you wonder why you should be reading this torrent of words, generously seasoned with names of mythological and historical figures, at times obscure or imaginary. But the last two make it up and are not for the faint of heart.

Style sample (makes me wanna turn it into an intertitle in a silent film): "Notre amour avait eu la simultanéité de deux coups de pistolet tirés en même temps, et qui tuent…"

The first four stories really make you wonder why you should be reading this torrent of words, generously seasoned with names of mythological and historical figures, at times obscure or imaginary. But the last two make it up and are not for the faint of heart.

Gemarkeerd

alik-fuchs | 11 andere besprekingen | Apr 27, 2018 | Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly (1808 – 1889), romantic with the sensibility of a decadent , self-styled dandy, teller of risqué novels and short stories, shocked readers and infuriated the authorities with the publication of Les Diaboliques. But there is much more to this captivating novel with its sumptuous, elegant language, well-crafted metaphors and highly visual and sensual imagery than simply shock value. Below are a number of themes common to the six separate tales comprising this novel:

Story within a story

For example, in The Crimson Curtain, the first-person narrator tells us as readers how one evening years ago while returning from a hunting trip he shared a carriage with a rotund, old dandy he calls Vicomte de Brassard. The carriage made a stop in a small provincial town for repair. Gazing up at an upper-story window of one of the town’s large buildings, a crimson curtain caught the narrator’s attention; he points out the captivating tint of the curtain to his riding companion. Ah, such are the twists of fate, since, as it turns out, that exact room with the crimson curtain was a dramatic marker for de Brassard’s life -- it all happened back in the day when he was but a 17 year old sublieutenant. And dandy de Brassard tells the tale.

Storytelling with a hook

There’s a point, usually about half way through, when something unexpected happens to propel the story into overdrive. And what variety of event are we alluding to here? Why, of course, as if lighting a fuse to a stick of dynamite, a woman ignites a man’s passion: BOOM! Now we’re reading a Barbey-d’Aurevilly-style spellbinding page-turner.

Dandyism

For Barbey d’Aurevilly, a dandy is not only a man scrupulously devoted to style, neatness and fashion but, as he describes Vicomte de Brassard, a dandy has a seductive beauty which seduce not only woman but circumstances themselves; has a careless disdain and repugnance of discipline; keeps several mistresses at the same time like seven strings of his lyre; drinks like a Pole; jests about his own immorality; belongs to his own times and transcends his times; and, lastly, above all else, scorns all emotion as being beneath him.

Conversation as a cultural highpoint

In all six of these Barbey d’Aurevilly tales, the characters raise conversation to an art form – probing inquiry; genteel exchange; elaborate, detailed storytelling with all the necessary color and nuance to convey a vivid, sensual picture; and, above all, a deep respect for the speaker, permitting one’s interlocutor time and space – none of those spurious interruptions commonplace in our current world: cutting a speaker off mid-sentence, answering cell-phones, texting, checking emails, looking at one’s watch (the ultimate insult). Indeed, engaging in conversation as a cultivated skill, a consummate refinement, similar to playing baroque music or painting in oils.

Woman as the real power player

19th century France: Victorian, bourgeois, patriarchal, or, in other words, a male-centered, conservative, reason-dominated society. But the dirty little secret for the upholders of Victorian patriarchy is our all-too-human life is fueled by passion and emotion, most particularly sexual emotion – sexual attraction, sexual arousal and, of course, erotic love. The power of each of these Barbey d’Aurevilly tales lies in the fact a female instigates or initiates the key action. Talk about turning those Victorian values upside down and shaking! No wonder the authorities hated Barbey d’Aurevilly and banned his 1874 novel – Les Diaboliques also gave the French reading public one of its first tastes of what came to be known as the Decadent Movement, with its smashing to bits the connection and linking of virtue/reward, vice/punishment, good morals/happiness and bad morals/unhappiness, as in Happiness in Crime, a tale of two adulterers and murderers who live happily ever after.

For a more specific rasa, let’s look at one of the tales. In The Greatest Love of Don Juan, we read of a Don Juan-like lover, Comte de Ravila, dining with twelve of his previous romantic conquests. Barbey d’Aurevilly describes the physical strength and mature sensuality of these sumptuous lovers: “Full curves and ample proportions, dazzling bosoms, beating in majestic swells above liberally cut bodices . . . “ And then he writes of the sheer psychic power of these ladies as the evening progresses: “They felt a new and mysterious power in their innermost being of which, until then, they had never suspected the existence. The joy of this discovery, the sensation of a tripled life force, the physical incitements, so stimulating to highly strung temperaments, the sparkling lights, the penetrating odor of so many flowers swooning in an atmosphere overheated with the emanations of all these lovely bodies, the sting of heady wines, all acted together.”

Then, one woman demands our Don Juan tell the story of the greatest love of his life. If effect, he is being asked to choose one of his lovers amongst the present company. Comte de Ravila tells his story but, turns out, the story is not at all what these ladies expected.

My take is Ravila did the exactly the right thing. True, his story was not a tale of wild, heart-stopping, hot-blooded passion – he probably had twelve equally erotic and fantastically romantic stories to tell on that subject, one for each lady present, however his story was of a completely different cast but a story that had, from his perspective, a happy ending – he escaped from the banquet with the real prize: his life.

What an impossible question to ask a man: to choose one woman amongst twelve surrounding him. If he did, he most likely would have been torn to shreds by eleven Dionysian-frenzied former lovers. That’s the way to think on your feet and save your skin, Ravila. Bravo!

Gemarkeerd

GlennRussell | 11 andere besprekingen | Feb 16, 2017 | Je suis tombée amoureuse de l'écriture de cet auteur. Quelle maîtrise dans les histoires emboîtées! J'ai adoré!

Gemarkeerd

Moncoinlecture | 1 andere bespreking | Apr 4, 2013 | Inspirado pela vida do herói Chouan Jacques Destouches. Muito bem escrito.

D'Aurevilly está sempre acompanhado, na minha cabeça, pela expressão "o dândi". Tenho vontade ler mais livros dele.

D'Aurevilly está sempre acompanhado, na minha cabeça, pela expressão "o dândi". Tenho vontade ler mais livros dele.

Gemarkeerd

JuliaBoechat | 1 andere bespreking | Mar 30, 2013 | He felt that this woman was going to tell him about things the like of which he’d never heard. He was no longer thinking about her beauty. He was looking at her as if he wanted to attend her autopsy.

[“Il lui semblait que cette femme allait lui raconter de ces choses comme il n’en avait pas entendu encore. Il ne pensait plus à sa beauté. Il la regardait comme s’il avait désiré assister à l’autopsie de son cadavre.”]

I once heard someone explain what ‘rococo’ meant by saying that it’s what happens when the baroque out-baroques itself. Barbey d’Aurevilly is what happens when the Romantic movement out-Romantics itself. These stories are obsessed with the Romanticism of high emotion and the sublime – only here it’s all much darker and more ‘decadent’: le sublime de l’enfer, as Barbey calls it at one point.

Each story centres on a woman whose passions prove fatal, for her or for someone else. But although the women are so central to what happens, they are without exception remote and unknowable, with utterly mysterious motives – almost like characters from a Norse saga. We know them only through the men that endlessly discuss them, lust after them, or hate them. They are – brace yourself as I reach for this adjective – positively sphingine, by which I mean cool, beautiful, mysterious and deadly.

Nothing interior illumated the outside of this woman. And nothing from the outside had any effect on her interior.

[“Rien du dedans n’éclairait les dehors de cette femme. Rien du dehors ne se répercutait au-dedans !”]

In the first story, ‘The Crimson Curtain’, the woman around whom the entire plot revolves does not speak even a single line. Although not the most shocking, this tale was in some ways my favourite, and passed the test of a good short story – that it works perfectly as an anecdote. I told it to my wife over a pint in the pub and she had her hand over her mouth for much of it. It bears an uncanny resemblance to the ‘Vincent Vega and Marcellus Wallace’s Wife’ chapter of Pulp Fiction, in that they both concern an illicit liaison that takes a sudden (very similar) U-turn for the worse.

The ending of that piece is very artful – in that almost everything that matters is left unresolved and up in the air. It’s an effect I like very much, and which Barbey deploys at several points throughout the book. There is a very modern feeling that what is left unsaid is much more exciting than any resolution could ever be – ‘what is not known,’ the narrator says somewhere, ‘multiplies by a hundred the impression of what is known.’

‘Ah!’ said Mlle Sophie de Revistal passionately. ‘It is the same in music as it is in life. What gives expressiveness to both are the silences more than the harmonies.’

[“—Ah ! — dit passionnément Mlle Sophie de Revistal, — il en est également de la musique et de la vie. Ce qui fait l’expression de l’une et de l’autre, ce sont les silence bien plus que les accords.”]

So you end up in this rather oppressive world of suspicion, rumour, and frightful supposition, peopled by these strange sphinxy women and the Byronic protagonists who are fascinated by them.

All but one of the stories are bracketed in reported speech from one of the characters, and with some longish introductions you might be tempted to wonder why the author doesn’t just hurry up and get on with it. But after a while, there emerges a strong sense that having these stories come out ‘in conversation’ is very important to Barbey – Les Diaboliques is, among other things, a love letter to the art of sparkling conversation, what he calls ‘the last glory of the French spirit’. (The orignal title for the collection was Conversational Ricochets.) Conversation is the primary tool on display here, although ‘At a Dinner of Atheists’ does open on a wonderful descriptive passage about a Valognes church at dusk which makes me wonder what might be on offer in his other books.

For all that these conversations may seem hopelessly dated to some readers now, there is a real cumulative effect building as you work your way through, and the last couple of stories here pack quite a punch. Impossible to imagine anything like this being published in England in 1874. ‘A Woman’s Vengeance’, the final piece, takes the clichéd 19th-century narrative of the poor innocent girl forced into a life of prostitution (Fantine from Les Misérables, for instance – a book which Barbey loathed) and turns it on its head in the most remarkable way. It takes in a surprisingly frank sex scene and includes a moment of almost medieval violence and jealousy.

Barbey was basically a royalist disillusioned by France's endless social revolutions, and he was sceptical about life in a democratic future. Instead of cheap moralising and hookers with hearts of gold, he gives you deep emotional doubt and damaged, incomprehensible strangers. Passion may drive these people to excesses of lust, intrigue and horror – but at their worst, Barbey seems to feel they are also at their most essentially human – beyond society’s conventions, and perhaps even, in some way that we are not, free.

[“Il lui semblait que cette femme allait lui raconter de ces choses comme il n’en avait pas entendu encore. Il ne pensait plus à sa beauté. Il la regardait comme s’il avait désiré assister à l’autopsie de son cadavre.”]

I once heard someone explain what ‘rococo’ meant by saying that it’s what happens when the baroque out-baroques itself. Barbey d’Aurevilly is what happens when the Romantic movement out-Romantics itself. These stories are obsessed with the Romanticism of high emotion and the sublime – only here it’s all much darker and more ‘decadent’: le sublime de l’enfer, as Barbey calls it at one point.

Each story centres on a woman whose passions prove fatal, for her or for someone else. But although the women are so central to what happens, they are without exception remote and unknowable, with utterly mysterious motives – almost like characters from a Norse saga. We know them only through the men that endlessly discuss them, lust after them, or hate them. They are – brace yourself as I reach for this adjective – positively sphingine, by which I mean cool, beautiful, mysterious and deadly.

Nothing interior illumated the outside of this woman. And nothing from the outside had any effect on her interior.

[“Rien du dedans n’éclairait les dehors de cette femme. Rien du dehors ne se répercutait au-dedans !”]

In the first story, ‘The Crimson Curtain’, the woman around whom the entire plot revolves does not speak even a single line. Although not the most shocking, this tale was in some ways my favourite, and passed the test of a good short story – that it works perfectly as an anecdote. I told it to my wife over a pint in the pub and she had her hand over her mouth for much of it. It bears an uncanny resemblance to the ‘Vincent Vega and Marcellus Wallace’s Wife’ chapter of Pulp Fiction, in that they both concern an illicit liaison that takes a sudden (very similar) U-turn for the worse.

The ending of that piece is very artful – in that almost everything that matters is left unresolved and up in the air. It’s an effect I like very much, and which Barbey deploys at several points throughout the book. There is a very modern feeling that what is left unsaid is much more exciting than any resolution could ever be – ‘what is not known,’ the narrator says somewhere, ‘multiplies by a hundred the impression of what is known.’

‘Ah!’ said Mlle Sophie de Revistal passionately. ‘It is the same in music as it is in life. What gives expressiveness to both are the silences more than the harmonies.’

[“—Ah ! — dit passionnément Mlle Sophie de Revistal, — il en est également de la musique et de la vie. Ce qui fait l’expression de l’une et de l’autre, ce sont les silence bien plus que les accords.”]

So you end up in this rather oppressive world of suspicion, rumour, and frightful supposition, peopled by these strange sphinxy women and the Byronic protagonists who are fascinated by them.

All but one of the stories are bracketed in reported speech from one of the characters, and with some longish introductions you might be tempted to wonder why the author doesn’t just hurry up and get on with it. But after a while, there emerges a strong sense that having these stories come out ‘in conversation’ is very important to Barbey – Les Diaboliques is, among other things, a love letter to the art of sparkling conversation, what he calls ‘the last glory of the French spirit’. (The orignal title for the collection was Conversational Ricochets.) Conversation is the primary tool on display here, although ‘At a Dinner of Atheists’ does open on a wonderful descriptive passage about a Valognes church at dusk which makes me wonder what might be on offer in his other books.

For all that these conversations may seem hopelessly dated to some readers now, there is a real cumulative effect building as you work your way through, and the last couple of stories here pack quite a punch. Impossible to imagine anything like this being published in England in 1874. ‘A Woman’s Vengeance’, the final piece, takes the clichéd 19th-century narrative of the poor innocent girl forced into a life of prostitution (Fantine from Les Misérables, for instance – a book which Barbey loathed) and turns it on its head in the most remarkable way. It takes in a surprisingly frank sex scene and includes a moment of almost medieval violence and jealousy.

Barbey was basically a royalist disillusioned by France's endless social revolutions, and he was sceptical about life in a democratic future. Instead of cheap moralising and hookers with hearts of gold, he gives you deep emotional doubt and damaged, incomprehensible strangers. Passion may drive these people to excesses of lust, intrigue and horror – but at their worst, Barbey seems to feel they are also at their most essentially human – beyond society’s conventions, and perhaps even, in some way that we are not, free.

1

Gemarkeerd

Widsith | 11 andere besprekingen | Feb 4, 2013 | In a similar manner to "Les Liaisons Dangeruese", this collection of 7 long stories presents a 19th century French aristocratic milieu that is elegant, subtle, and cold as ice. The She-Devils in each story are women who exert some memorable and remarkable effect on a male raconteur. Each story is more violent, overwrought, and improbable than the one before; they're never less than engrossing, and even funny in a utterly caustic way (D'Aurevilly is chuckling as he writes, but no one IN the stories seems to have much sense of humor.) Love and sexuality are presented as absolutely cruel drivers with nothing redeeming about them; relationships even between parents and children are selfish and egoistic.

I loved reading this. I wouldn't want to live in the world of these stories, but they were hella entertaining.½

I loved reading this. I wouldn't want to live in the world of these stories, but they were hella entertaining.½

2

Gemarkeerd

NancyKay_Shapiro | 11 andere besprekingen | Jan 3, 2013 | Despite the author's misogyny, monarchism, love of military tradition, racism, and often overblown prose, I found these six tales within tales of proud and passionate woman whose behavior seems evil, if not diabolical, to the bored and blasé men who tell and listen to their stories, weirdly compelling -- at least for the first two-thirds or so of the book. The narrators and listeners are men who miss the passing of Napoleon's army and Empire, and long for the past when their aristocratic titles and military exploits meant something. Shocking when first published, and subsequently banned, in 1874, this collection has moments that are still quite shocking today, although it is apparently now considered a classic in France. D'Aurevllly was steeped in French military and aristocratic history, as as in the classics of the Greek and Roman eras, as the book is filled with references that made me occasionally resort to Wikipedia but more often regret the lack of explanatory footnotes or endnotes. The edition I read, which I picked up when bookstore browsing because it looked intriguing, was also marred by typographical errors.

2

Gemarkeerd

rebeccanyc | 11 andere besprekingen | Dec 2, 2012 | « La ville que j’habite en ces contrées de l’Ouest, – veuve de tout ce qui la fit si brillante dans ma prime jeunesse, mais vide et triste maintenant comme un sarcophage abandonné, – je l’ai, depuis bien longtemps, appelée : « la ville de mes spectres », pour justifier un amour incompréhensible au regard de mes amis qui me reprochent de l’habiter et qui s’en étonnent. C’est, en effet, les spectres de mon passé évanoui qui m’attachent si étrangement à elle. Sans ses revenants, je n’y reviendrais pas ! »

Dans cette ville normande Barbey d’Aurevilly évoque le souvenir de l’ amour incestueux d’un frère et d’une soeur, criminels aux yeux de la loi et des moeurs, qui périrent sur l’échafaud.

Dans cette ville normande Barbey d’Aurevilly évoque le souvenir de l’ amour incestueux d’un frère et d’une soeur, criminels aux yeux de la loi et des moeurs, qui périrent sur l’échafaud.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | Jan 26, 2012 | Première nouvelle de Barbey d'Aurevilly publiée dans la Revue de Caen.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | Jan 26, 2012 | Un prêtre marié est un roman de l’écrivain français Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly paru en 1864. Le roman est construit conformément au schéma traditionnel du récit aurévillien. Il s'agit en effet d'un récit enchâssé où le narrateur initial cède la parole à un personnage secondaire qui devient à son tour narrateur. Il conte l’histoire de Jean Sombreval, ancien prêtre devenu athée et même marié dans le Paris révolutionnaire, qui va devoir subir la vengeance d’un Dieu moins charitable que jamais. Sombreval, après la mort de sa femme, conçoit une dévotion toute particulière pour sa fille unique, Calixte. Or Calixte est passionnément chrétienne, à tel point qu’elle est entrée dans l’ordre du carmel, se jurant de ramener son père à la foi. L’intrigue se déroule dans le village originaire de Sombreval, où s’affrontent l’ensemble des forces issues de la Révolution : catholicisme contre athéisme, aristocrates contre parvenus, passé contre présent. Le roman est nourri de récits populaires empruntés au vieilles légendes normandes auxquels se mêle une culture religieuse et biblique plus ou moins explicite. Le personnage inquiétant de la Malgaigne, vieille nourrice de Sombreval, incarne ainsi la survivance d'une France archaïque et superstitieuse opposée au rationalisme athée du prêtre apostat. En butte aux médisances des villageois unanimement hostiles à son retour, Sombreval s'isole avec Calixte dans un château pour la couvrir d'une attention teintée d'idolâtrie. Il la chérit d'un amour pur et religieux dont la rumeur s'empare bien vite pour l'accuser d'inceste. Les expériences étranges auxquelles Sombreval se livre chaque soir, dans son château, ne sont pas sans rappeler la diabolique image de Faust. Ayant renié sa foi pour s'adonner aux sciences, notamment l'alchimie et la médecine, il espère découvrir un remède qui soignera Calixte atteinte d'une maladie qu'aucun savant de parvient à guérir. Néel de Néhou, un jeune aristocrate aux allures chevaleresques conforme à l'idéal nostalgique de l'auteur, cherche obstinément à gagner les faveurs de Calixte, au risque de tout perdre. Mais sa vénération ne trouve qu'une réponse d'amie ou de sœur auprès de la jeune Carmélite exclusivement tournée vers Dieu. Malgré les noirs avertissements de la Malgaigne, il se jette corps et âmes dans une passion impossible et tragique qui nouera son destin avec celui du couple antagoniste formé par le père et la fille. L'ouvrage joue donc sur des oppositions sociales, religieuses et morales qu'on ne saurait pourtant résumer à l'affrontement de l'ange et de la bète.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | 1 andere bespreking | Jan 26, 2012 | Après sa conversion au catholicisme, Barbey d’Aurevilly ne cesse de pourfendre avec verve toutes les modes intellectuelles et artistiques de son siècle : le libéralisme, le positivisme, et surtout l’ « humanitarisme » de Hugo et de Zola.

Dans son œuvre de romancier et de conteur, il manifeste cependant lui-même un anticonformisme ostentatoire qui le rapproche des écrivains « maudits » comme Baudelaire, dont il défend le « dandysme » et le « satanisme ». Ce sont d’ailleurs ces valeurs et de la différence et de l’étrange poussé jusqu’au démoniaque qui inspirent le long récit d’Une histoire sans nom, dans lequel se déploie sa passion pour les questions de superstition, d’ensorcellement et de possession.

Dans ce passage, la servante dévouée, est allée en pèlerinage sur la tombe du bienheureux Thomas de Biville dans l’espoir de sauver sa jeune maîtresse, Lasthénie, du mal mystérieux qui la ronge. Sur le chemin du retour elle rencontre « une chose surnaturelle et formidable » qui s’impose à elle comme un sinistre présage.

Dans son œuvre de romancier et de conteur, il manifeste cependant lui-même un anticonformisme ostentatoire qui le rapproche des écrivains « maudits » comme Baudelaire, dont il défend le « dandysme » et le « satanisme ». Ce sont d’ailleurs ces valeurs et de la différence et de l’étrange poussé jusqu’au démoniaque qui inspirent le long récit d’Une histoire sans nom, dans lequel se déploie sa passion pour les questions de superstition, d’ensorcellement et de possession.

Dans ce passage, la servante dévouée, est allée en pèlerinage sur la tombe du bienheureux Thomas de Biville dans l’espoir de sauver sa jeune maîtresse, Lasthénie, du mal mystérieux qui la ronge. Sur le chemin du retour elle rencontre « une chose surnaturelle et formidable » qui s’impose à elle comme un sinistre présage.

1

Gemarkeerd

vdb | Jan 26, 2012 | Extrait de la Préface: "L’Amour impossible est à peine un roman, c’est une chronique, et la dédicace qu’on y a laissée atteste sa réalité. C’est l’histoire d’une de ces femmes comme les classes élégantes et oisives – le high life d’un pays où le mot d’aristocratie ne devrait même plus se prononcer – nous en ont tant offert le modèle depuis 1839 jusqu’à 1848. À cette époque, si on se le rappelle, les femmes les plus jeunes, les plus belles, et, j’oserais ajouter, physiologiquement les plus parfaites, se vantaient de leur froideur, comme de vieux fats se vantent d’être blasés, même avant d’être vieux. Singulières hypocrites, elles jouaient, les unes à l’ange, les autres au démon, mais toutes, anges ou démons, prétendaient avoir horreur de l’émotion, cette chose vulgaire, et apportaient intrépidement, pour preuve de leur distinction personnelle et sociale, d’être inaptes à l’amour et au bonheur qu’il donne... C’était inepte qu’il fallait dire, car de telles affectations sont de l’ineptie. Mais que voulez-vous ?"

Gemarkeerd

vdb | Jan 26, 2012 | Les Diaboliques est un recueil de six nouvelles de Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly, paru en novembre 1874 à Paris chez l'éditeur Dentu.

Le projet de ce recueil de nouvelles devait s'intituler à l'origine Ricochets de conversation. Il fallut cependant près de vingt-cinq ans à Barbey pour le voir paraître puisqu'il y travaillait déjà en 1850 lorsqu'il fit paraître Le dessous de cartes d'une partie de whist dans le journal La Mode dans un feuilleton en trois parties, La Revue des Deux Mondes l'ayant refusé. Barbey revint en Normandie à la faveur des événements de la Commune et l'acheva en 1873.

Le projet de ce recueil de nouvelles devait s'intituler à l'origine Ricochets de conversation. Il fallut cependant près de vingt-cinq ans à Barbey pour le voir paraître puisqu'il y travaillait déjà en 1850 lorsqu'il fit paraître Le dessous de cartes d'une partie de whist dans le journal La Mode dans un feuilleton en trois parties, La Revue des Deux Mondes l'ayant refusé. Barbey revint en Normandie à la faveur des événements de la Commune et l'acheva en 1873.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | 11 andere besprekingen | Jan 26, 2012 | Œuvre de jeunesse de Barbey, Le Cachet d'onyx est la seule nouvelle qui ait été publiée à titre posthume. Pour expliquer cette publication posthume, on peut mettre en avant le fait que Barbey a très tôt condamné ses œuvres de jeunesse, avant de les reprendre plus tard. Une autre explication est que le dénouement de la nouvelle est le même que celui d'une de ses Diaboliques : un dîner d'athées. Le Cachet d'onyx perdait ainsi de son intérêt. L'influence d'Othello de Shakespeare est prégnante tout au long de la nouvelle notamment en ce qui concerne le thème de la jalousie. Barbey évoque aussi Jean-Jacques Rousseau et sa Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse : "Il y a une belle imposture de Rousseau, c'est quand il montre dans son Héloïse que celle qui a aimé une fois, qui s'est donné corps et âme, baisers et sourires, peut devenir, mariée à un autre que celui qui l'a possédée, épouse tendre et soumise, mère de famille irréprochable, chaste prêtresse des dieux domestiques..." Dans cette nouvelle, on remarque un Barbey jeune, qui critique le dandysme, et qui offre un court récit déconcertant, hésitant entre passages romanesques passionnés et philosophie, et qui dévoile au travers d'un style encore quelque peu maladroit les thématiques les plus marquantes de l'œuvre Aurevillienne.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | Jan 26, 2012 | L’histoire relate un évènement fondateur du récit ; l’engagement de l’abbé de la Croix-Jugan auprès des Chouans. Lorsque ce dernier pense sa cause perdue, il tente de se suicider et renie son humilité de prêtre. Il survit malgré une horrible blessure au visage, signe de sa rébellion. Quelques années plus tard, « lorsqu’on rouvrit les églises » nous retrouvons cet ancien moine aux vêpres de Blanchelande.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | 1 andere bespreking | Jan 20, 2012 | Un homme, Marigny, pris entre une sylphide et une catin. La sylphide, c'est sa femme, Hermangarde ; la catin : Vellini, une Espagnole qui n'est même pas belle mais lui a empoisonné le coeur, le sexe et le sang. Marigny, retiré dans le Cotentin, s'est juré de rompre. Mais, un jour qu'il se promène à cheval le long de la mer, il retrouve Vellini ; et la pure Hermangarde, dans une des scènes les plus « diaboliques » de l'oeuvre de Barbey, sous une effroyable tempête de neige, assistera, collée à la fente d'une fenêtre, aux furieux ébats du couple et manquera d'en mourir. « Tu passe-ras sur le coeur de la jeune fille que tu épouses pour me revenir ! » avait prédit la Vellini.

Publié en 1851, le roman fit scandale mais Théophile Gautier déclara : « Depuis la mort de Balzac, nous n'avons pas encore vu un livre de cette valeur et de cette force. »

Publié en 1851, le roman fit scandale mais Théophile Gautier déclara : « Depuis la mort de Balzac, nous n'avons pas encore vu un livre de cette valeur et de cette force. »

Gemarkeerd

vdb | Jun 7, 2011 | Le chevalier des Touches, célèbre chef chouan, fit trembler le pouvoir. Dans ce roman violent où- s'affrontent les ombres et les lumières, le tragique et l'humour, Barbey d'Aurevilly ressuscite à travers les souvenirs de six personnages vieillis et fa-lots un rebelle hautain et inspiré. Ce récit, par l'auteur des Diaboliques a d'étranges résonnances modernes.

Gemarkeerd

vdb | 1 andere bespreking | Jun 7, 2011 | M. Barbey d'Aurevilly est une des plus fortes vocations littéraires que je sache ; et sa maîtresse faculté, sa plus belle force, son plus grand souffle, à lui, c'est l'Expression, c'est-à-dire le don de l'irrésistible éloquence... L'enthousisme flambe continuellement dans ce livre et promène sur toutes les pages sa terrible langue de feu, ondoyante et multiple... ' Léon Bloy

Gemarkeerd

vdb | 1 andere bespreking | Aug 14, 2010 | Links

BNF, Ressources sur l'auteur (French)

Wikipedia (English)

Wikipedia (French)

Persée, Contributions de l'auteur (French)

Onze site gebruikt cookies om diensten te leveren, prestaties te verbeteren, voor analyse en (indien je niet ingelogd bent) voor advertenties. Door LibraryThing te gebruiken erken je dat je onze Servicevoorwaarden en Privacybeleid gelezen en begrepen hebt. Je gebruik van de site en diensten is onderhevig aan dit beleid en deze voorwaarden.

______

Not an easy reading experience as such but my engagement with it made the language much easier to work with, and I had a big breakthrough moment during reading which motivated me even further. Glad I'm now dedicating 90 minutes-2 hours or so before sleeping to reading rather than doing drips and drabs when I get the chance as getting lost in these stories was great both for my own enjoyment of them and for getting myself into an immersive flow state. Shocked at how quickly I read this too as taken altogether this is my longest yet, and it took me less than a fortnight - I've come a long way from (enjoyably) struggling through Le Grand Meaulnes for a month.